Published at The Conversation, Tuesday 4 July

The government has announced a plan to increase university fees. Most bachelor degree students starting in 2018 would pay, depending on discipline, between A$700 to A$1,700 more than now.

The prospect of higher fees raises concerns about whether higher education is still worthwhile. With subdued job growth since the global financial crisis and many more students at university, educational choices are more complex now than a decade ago.

While some people principally choose higher education for non-financial reasons, many students attend primarily as a pathway to better employment prospects.

The Grattan Institute’s submission to the Senate inquiry into the 2017 budget’s higher education package examined these concerns.

Unemployment and full-time work

Graduate employment has deteriorated since 2008. In 2016, 14% of graduates were unemployed four months after graduation. While unemployment falls as graduates spend more time in the workforce, it is still an issue three years after graduating. For 2013 graduates, about 8% were unemployed in 2016.

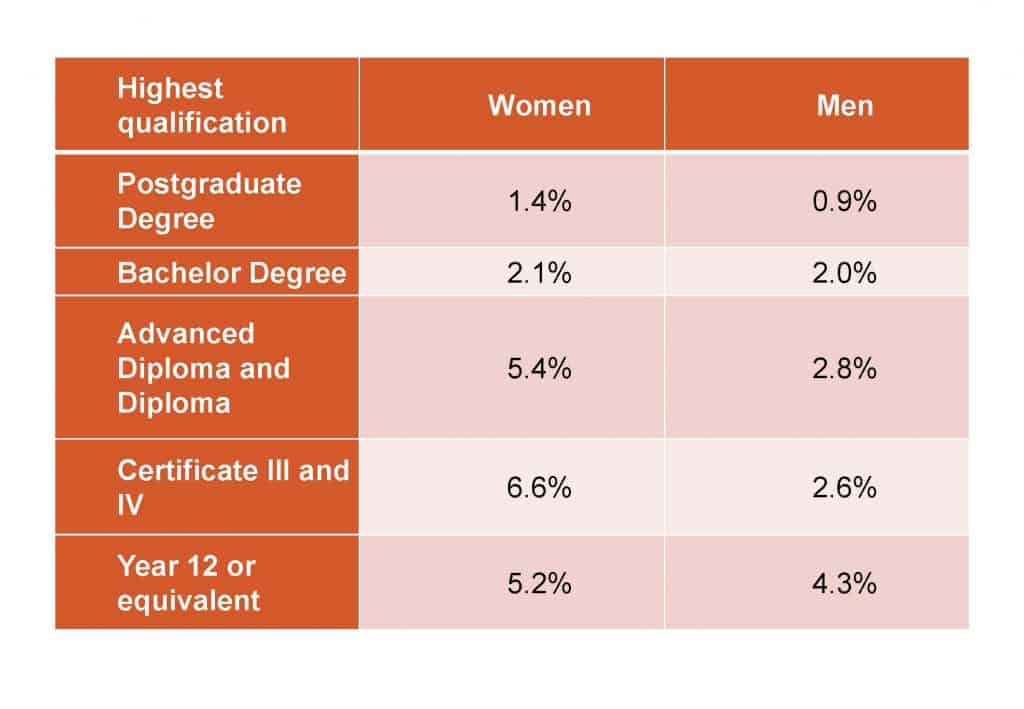

Over the longer run, however, graduates are less likely to be unemployed than people with lower levels of education attainment. This is especially the case for women. Bachelor degrees more than halve their risk of unemployment, as the table below shows.

Full-time work has also become harder to find. In 2016, about 70% of graduates looking for a full-time job found one within four months of graduation. This was a little better than in the preceding years. But their rate is still well below the full-time employment rates of the pre-2008 cohorts.

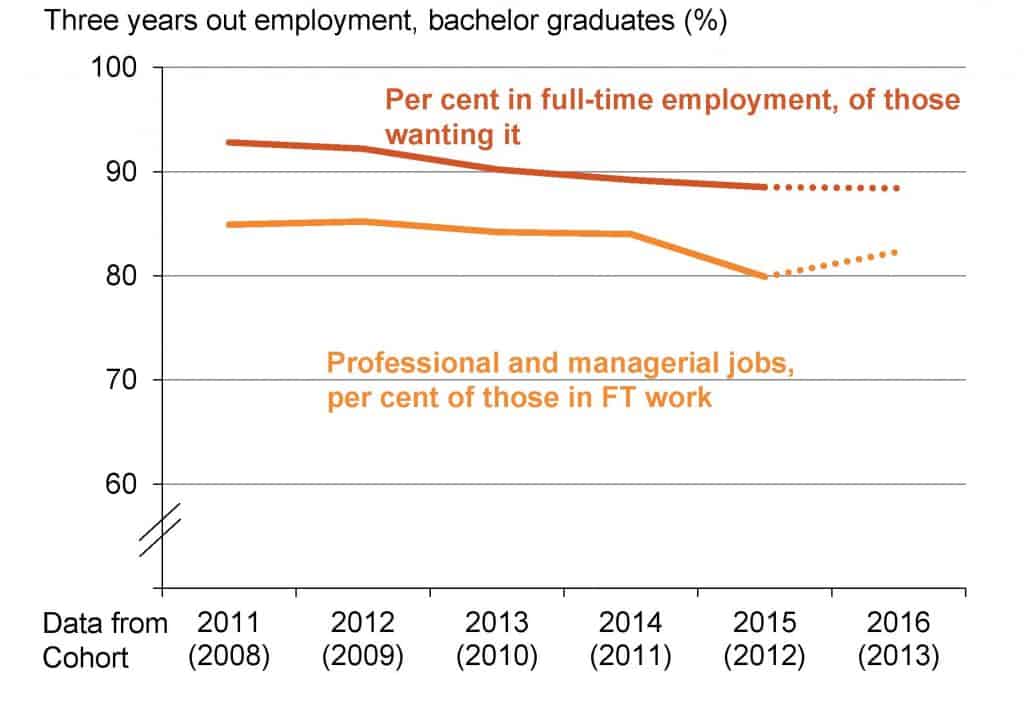

As graduates stay in the workforce, full-time employment rates improve, but remain below those of earlier graduate cohorts, as the graph below shows.

Professional jobs

Job quality is also an issue, with students who graduated after 2008 making slower transitions to full-time professional or managerial jobs, as shown in the graph above. Our most recent data from 2016 shows a mildly positive trend.

But as with the four-months-out figures, the overall trend for three years out is down over time. Despite this, graduates still have better access to professional jobs than people with other qualifications.

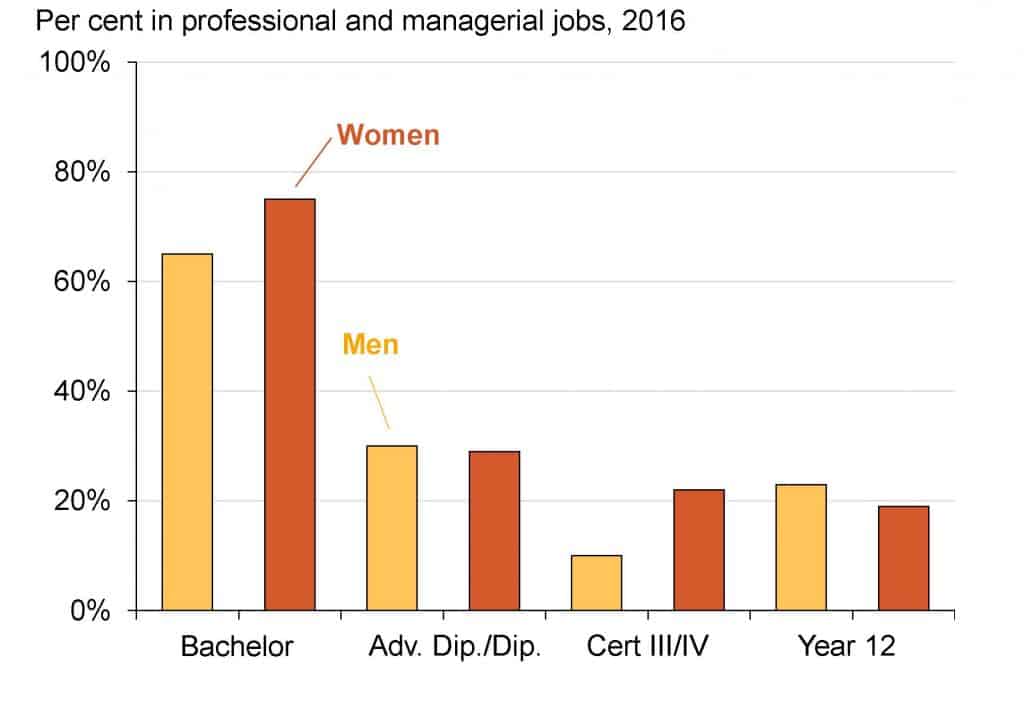

Among younger cohorts, three quarters of employed female graduates have a professional or managerial job – more than twice the proportion of their contemporaries with upper-level vocational qualifications or Year 12.

As the figure below shows, the professional and managerial share for male graduates is lower at 65%, partly due to more men than women working in technical occupations.

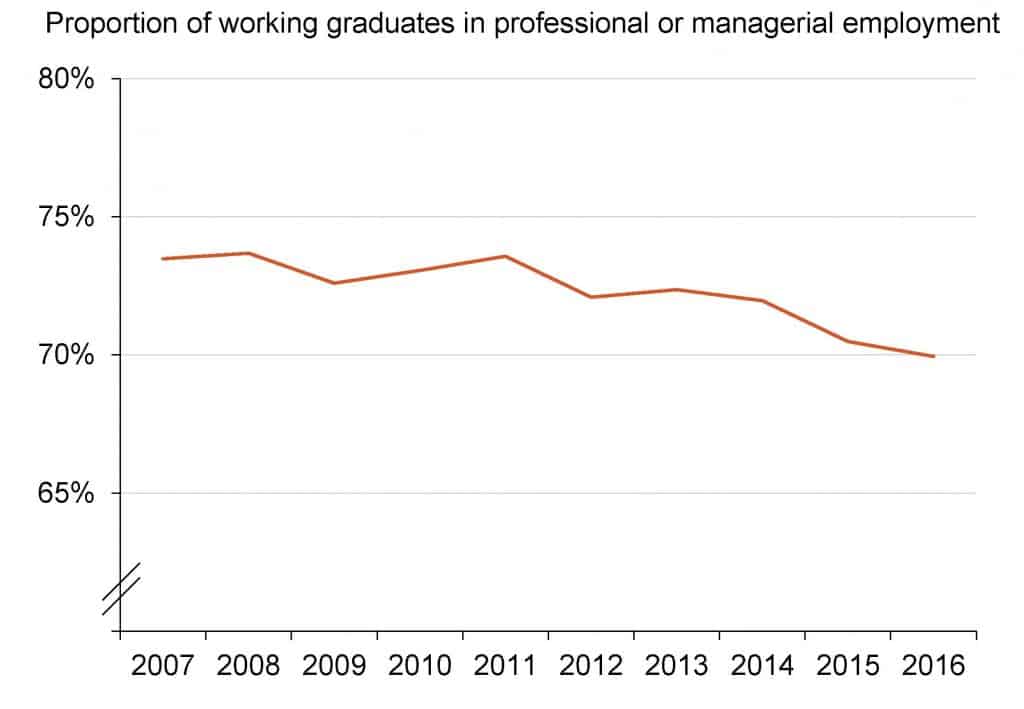

Yet because graduate numbers have been growing faster than professional jobs, the share of graduates in these jobs is not as large as in the past, as shown below.

Earnings

Previous research finds those with a bachelor degree earn more than those with Year 12 or vocational post-school qualifications.

Based on 2011 Census data, a male graduate was expected to earn 20% more than a diploma holder and 61% more than a school leaver.

The premium was higher for women. A median female graduate was expected to earn 31% and 70% more than a diploma holder or a school leaver respectively.

Given the changes to the economy and growth in graduate numbers, the premium is expected to be lower now than in 2011. While waiting for the 2016 Census income data, the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Characteristics of Employment survey gives us a guide to what is happening.

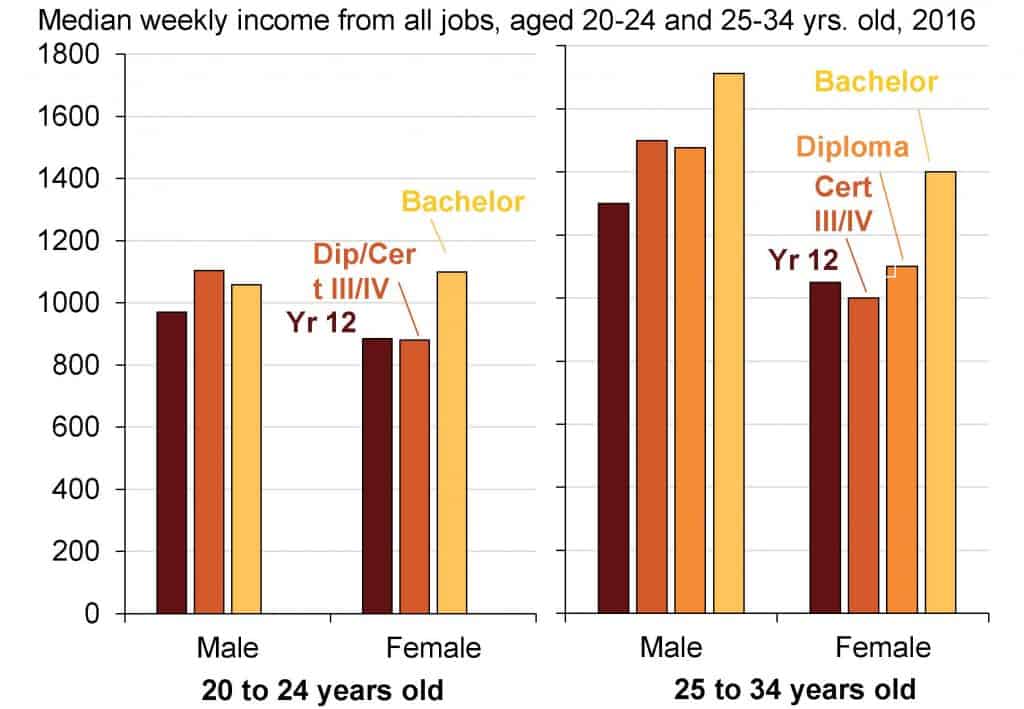

At ages 20 to 24, both male and female graduates earn more than their counterparts with only Year 12. Women earn $215 more a week and men earn $90 more, as shown below.

In this age group, men with upper-level vocational qualifications earn slightly more than male graduates. This is not the case for women, who gain little, if any, financial benefit from vocational qualifications compared to finishing their education at Year 12.

By age 25 to 34, bachelor degrees typically offer higher pay for both men and women. Women earn $350 a week more and men earn $410 more compared to Year 12, as shown in figure 4.

By this age bracket, men with bachelor degrees earn more than those with upper-level vocational qualifications. However, the benefit of having vocational qualifications over year 12 was apparent only for men. As with their younger cohort, women aged between 25 to 34 gain little from upper-level vocational qualifications compared to Year 12 only.

Overall, the earnings data suggest higher education remains financially attractive for most students, and the small proposed fee increases should not materially affect that. The extra fees are equivalent to about a week’s pay for most graduates.

Yet employment outcomes are not as good as in the past, which increases the risk that higher education will not pay off, at least in a financial sense. This will be true for the foreseeable future whether university fees increase or not.

Young people who are less academically inclined need carefully to consider which educational option is best for them. Especially for men, vocational qualifications may be lower-risk options than a bachelor degree.

![]()

Published at

Published at