Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 13 May

The government promised a “dull and routine” budget. This is one promise it kept. There are relatively few new measures, they are not supposed to cost much, and there were no hidden nasties suddenly announced on budget night. The forecasts imply slightly better economic growth next year, and a return to healthy economic growth thereafter.

Relative to last year, the budget is more likely to keep more people happy. But it does almost nothing to solve our long-term budgetary problems.

The net impact of the budget measures is close to zero by 2018-19. New spending on childcare is paid for by changes to family tax benefits that are yet to pass the Senate. Other than the Netflix tax and the multinational tax avoidance policy (not costed due to uncertainties in its implementation) there is almost nothing in the way of new revenue measures.

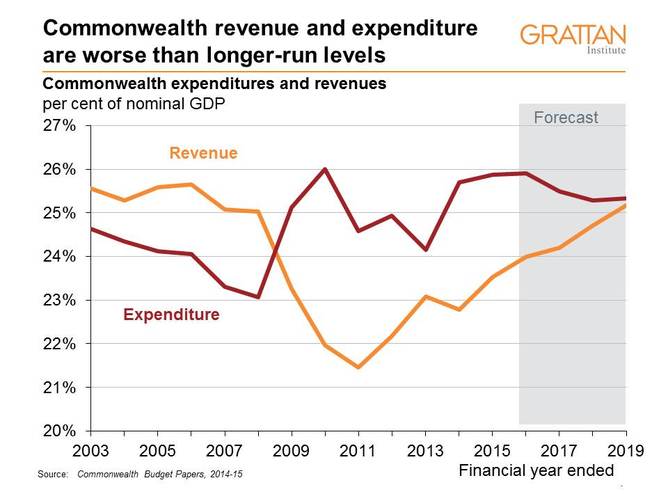

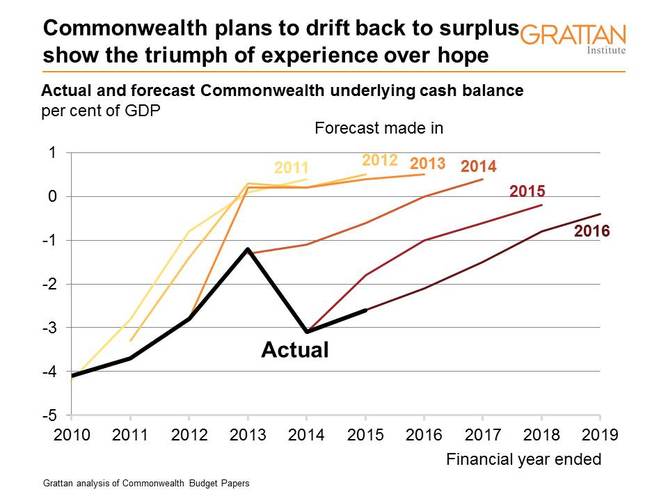

Instead, the budget bottom line improves between 2014-15 and 2018-19 because of rosy forecasts of modest reductions in spending and substantial increases in tax collections relative to the size of the economy. The government forecasts that the deficit will narrow from $41 billion (2.6% of GDP) in 2014-15 to only $7 billion (0.4% of GDP) in 2018-19.

Spending reduces primarily because the budget assumes that without policy interventions, almost every major category grows slower than the economy. And revenue increases, primarily because personal income taxes grow rapidly.

To return to surplus without policy heavy lifting requires a lot to go right. Expenditure growth is forecast to rise by only 1.1% a year on average until 2017-18. This would be remarkable restraint given long term growth is more than 3% each year. It would be particularly remarkable in a period that spans an election year.

Forecast growth in personal and corporate tax receipts rely on a quick economic recovery. Nominal GDP growth is forecast to rise from 1.5% in 2014-15 to 5.5% by 2016-17 – implying both a return to the solid real GDP growth typical of the early 2000s, and an end to the fall in minerals prices. Personal income tax collections also assume that wages again grow faster than inflation when this year there was almost no growth in real wages. And it requires that government resists the inevitable, and not unreasonable, demands for personal tax cuts as a person on average full time weekly earnings moves into the second top tax bracket some time in 2015-16. A lot of things have to go right at once.

This organic drift to surplus has been the underlying strategy of the last six budgets. However, so far, experience has triumphed over hope. Since 2011, each budget has forecast surpluses on the horizon, and each year that date pushed out further. It’s not clear why this time will be different.

As well as asking people to accept these rosy assumptions, the budget also requires impressive mental gymnastics to reconcile this year’s budget with last year’s rhetoric.

Last year the government said everyone should contribute to the task of budget repair through a range of unpopular budget measures. One year later and many of those measures have either been abandoned (GP co-payments, pension indexation and six-month waiting periods for Newstart allowance) or are unlikely to pass the Senate (changes to Family Tax Benefits and higher education reforms). Some groups – particularly small business – are simply winners.

Last year Tony Abbott was the “infrastructure Prime Minister”. In this year’s budget, Commonwealth spending on transport infrastructure falls from 0.5% of GDP in 2015-16 to 0.3% in 2018-19. The largest addition to infrastructure spending is for the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility, which will only cost .02% of GDP per year, and even that relies on the government finding commercial partners yet to be identified.

Last year, a “gold standard” paid parental scheme was a “signature policy”. This year, parental leave payments are in effect being cut for those who already receive them from their employer.

Last year, we were told that government was too large and spending was too high. This budget proposes four years in which Commonwealth spending will be a greater proportion of GDP than all but the two years of financial crisis under the Rudd-Gillard governments.

Last year we were told this government would fix the budget through spending reductions, not higher taxes. This year, budget repair is supposed to result primarily from the tax take increasing by 1.7% of GDP in four years.

But the greatest cognitive dissonance comes from the government’s fundamental approach to budget repair. While doing nothing was not an option in the face of the “debt and deficit disaster” a year ago, the government has done precisely that. This budget recognises that 2014-15 will be much worse than forecast in last year’s budget. It is probably sensible to slow the pace of budgetary repair in the face of a weakening economy. However, if the recovery forecast for 2016-2018 is as strong as the budget forecasts, then there needs to be substantially more budget repair in these later years. Australia cannot afford otherwise.

It remains to be seen if this budget is really different, and if its messages cut through despite the abrupt changes in direction. Its contents might be dull. But the moves it provokes are likely to be fascinating.

![]()