As a recent Grattan Institute report showed, Australian governments face a decade of deficits unless governments make tough decisions to both reduce expenditure and increase taxes. How does the 2013-14 budget measure up?

A key budget aim appears to be getting to a rounding error surplus in 2015-16, and therefore at least appearing to deal with the long-term deficit.

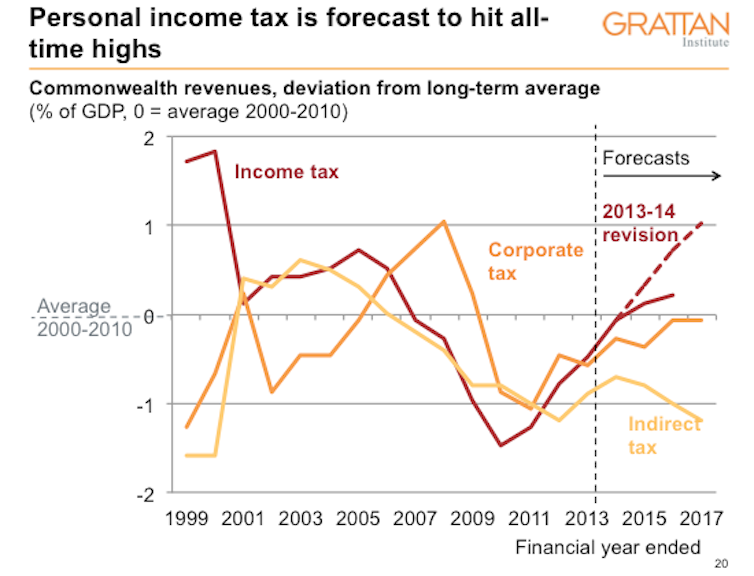

There are some heroic assumptions to get to this result. Personal income tax is projected to jump from 10.3% of GDP this year, to 11.5% in 2015-16 – about an extra $20 billion in 2015-16. The new medicare levy, the deferral of the carbon tax cuts and other minor changes add to about $5 billion, and bracket creep will help as well. But still, it would amount to the highest level of income tax since as a percentage of GDP since 2000.

Meanwhile, on the expenditure side there are equally optimistic forecasts. Overall real expense growth is happily constrained to 2.2% in 2014-15, 1.4% in 2015-16 and 2.1% in 2016-17. This would be a radical change from the last 15 years.

Through the ups and downs of the financial crisis, long-run expenditure growth was 3.4% year on year. The last time real expense growth was less than 2.5% was the Costello “tough budget” in 2002-03. If expense growth is closer to historical trends – and there are not obvious savage cuts in this budget to change things materially – expenses could be much worse than forecast in 2015-16.

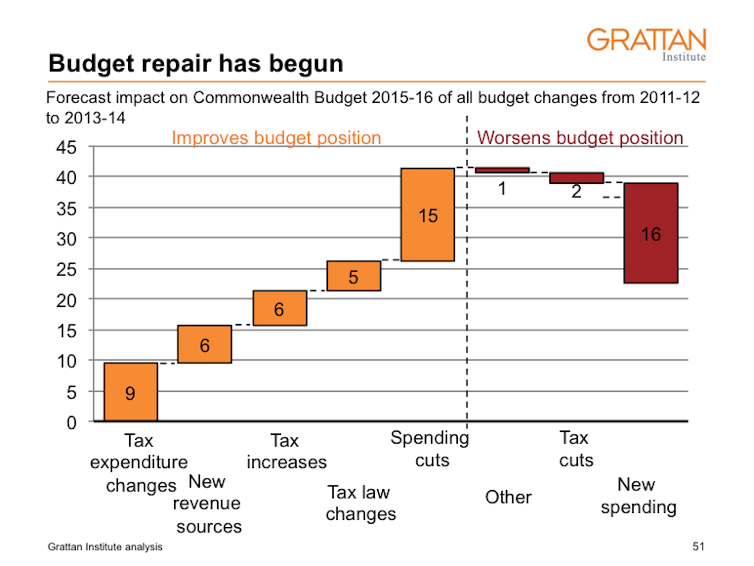

However, there are some improvements to the underlying budget position. Policy measures in the last three budgets introduced spending cuts that will roughly equal the policies that increase spending for the 2015-16 year. The bottom line has been substantially improved by tax measures that increase revenues by about $22 billion per year in 2015-16. This is a material step in the right direction towards structural budget repair.

Nevertheless, eliminating the structural deficit will require much more of this. From the optimistically balanced budget in 2015-16, future budgets will have to absorb a series of hits.

Most of the spending for DisabilityCare – $9 billion per year – will start after 2015-16. Many believe that the carbon and mining tax will raise $6 billion per year less than the already-reduced forecasts. Expenses could be $14 billion per year higher if growth is closer to historic trends than forecasts.

And of course, if minerals prices are lower than forecast, the budget hole could be even bigger. A future Commonwealth Treasurer may have a lot of work to do, both reducing spending and increasing revenue.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.