Published at The Conversation, Thursday 16 June

Whichever party wins the 2 July election, changes to the Higher Education Loan Programme (HELP) scheme are on their way.

Both parties support lowering the threshold for starting repayment, although by different amounts. Both would abolish HELP debt reductions for some teaching and nursing graduates. But the Liberals are floating more radical ideas for fixing HELP’s financial problems.

The May budget estimated HELP’s 2016-17 costs at A$2.6 billion, mostly in interest subsidies and debt not expected to be repaid, commonly called doubtful debt.

A Parliamentary Budget Office report forecasts rapid escalation of these costs. This is why HELP reform is on the political agenda.

In March, a Grattan Institute report argued that lowering the income threshold for repaying HELP debt was essential for controlling the scheme’s costs.

Different repayment thresholds being proposed

For 2016-17 the threshold is $54,869. Anyone earning less than that repays nothing; anyone earning more repays at least 4% of their income.

Labor says that it would reduce the initial threshold to $50,638, with a 2% of income repayment rate, then the 4% rate kicking in at the current threshold.

The $50,638 threshold is a budget measure from the 2014 Coalition budget. But since then, Liberal thinking has moved on.

In May 2016, the Liberals released a discussion paper on future higher education policy. In it they mooted a much lower threshold of between $40,000 and $45,000.

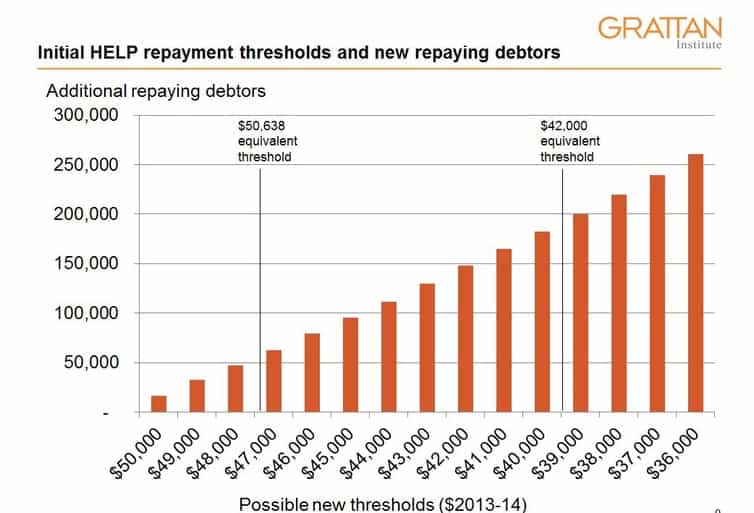

Our Grattan report also suggested an initial threshold in this range, of $42,000. The reason why can be seen in the chart below. It adjusts a $50,638 threshold for 2016-17 back to 2013-14, the last year for which we have income data on HELP debtors, to see how many more people would repay at different thresholds.

A $50,638 threshold does too little to bring more HELP debtors into repayment. With a 2% of income repayment rate, it would increase annual HELP compulsory repayments by only 4%.

Will low-income graduates be more affected?

Labor argues that a $42,000 threshold would affect lower-income earners too much.

Because HELP debtors often live with other people, their personal income is not always a reliable guide to their living standards. They share expenses and sometimes income with others. Grattan’s analysis found that half the debtors who would be affected by a $42,000 threshold live with a partner.

These partnered debtors are of particular interest in HELP policy. The loan scheme is designed to protect people in financial hardship, but 70% of partnered debtors live in households with combined after-tax disposable incomes exceeding $80,000 a year.

These partnered HELP debtors don’t need to work full-time to have a good standard of living, increasing the risk they will never repay.

Basing HELP repayments on family income, as mentioned in the Liberal discussion paper, would fix this problem. But family-income based repayment is unlikely to happen due to major fairness and implementation problems. Reducing the threshold to lift repayments is a better way of reducing doubtful debt.

Of the single HELP debtors affected by a $42,000 threshold, 80% would end up with after-tax disposable incomes between $35,000 and $45,000 a year (including untaxed income). For many in this group, low income is temporary as they transition into full-time work or wait for a pay rise.

While a growing share of first full-time graduate jobs pay less than the threshold, median graduate salaries increase by a third in the first three years after graduation.

Nobody pretends that it would be easy to live on your own earning $42,000 a year. But the threshold would remain well above social security benefits or the minimum wage, now about $35,000 a year. It’s not clear why HELP debtors should be treated so generously compared to other forms of government income protection, especially when many of them are not poor.

A lower threshold of around $42,000 would still achieve HELP’s income protection aims: students would not have to pay their fees up-front, repayments would still adjust to earnings, and HELP debtors on low incomes would not have to repay anything.

Ending HELP benefits for careers already chosen

While differing on thresholds, Labor and Liberal now agree on ending the HECS-HELP benefit. This benefit is a reduction in HELP debt of just under $2,000 a year to people with degrees in certain fields working in related occupations, sometimes in particular locations. In practice, most of the money goes to teachers and nurses.

The main argument against the HECS-HELP benefit is simple: it pays graduates to do what they were going to do anyway. If someone spends three or four years studying to be a teacher or a nurse, do they become a teacher or a nurse because their HELP debt will be reduced by $2,000 a year, or because that is their chosen career?

The benefit is a windfall gain to people who find out they could save money by filling in Australian Taxation Office forms.

Unfortunately, Labor is promising another similar scheme, by writing off the HECS-HELP debts of science, technology, engineering and maths graduates who finish the degree they started.

Neither Labor nor Liberal has confirmed policies on HELP that would significantly affect large numbers of students or graduates, although the Liberals are leaning towards major threshold reform.

But as HELP’s costs steadily increase, it is likely that both parties will develop such policies in the coming years. They just won’t announce them during an election campaign.

![]()