Published at The Conversation. Monday 17 December

The Morrison government wants next year’s election to be about economic management. So understandably, it’s using the improved bottom line in the Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) to talk up its economic credentials. But the numbers in MYEFO show it has failed to hit many of its own targets.

Target 1: Surpluses on average over the cycle

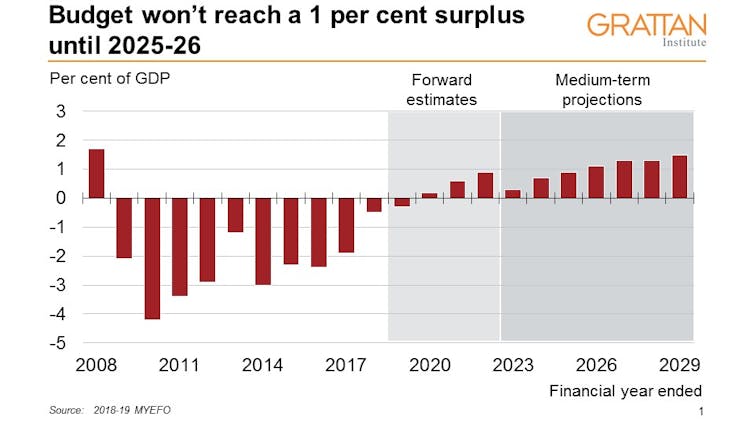

The government’s overarching fiscal objective is to deliver budget surpluses: not just in one year but on average over the economic cycle. MYEFO indicates the government is expecting a $5.2 billion deficit in 2018-19 (0.3% of GDP). It will be the 11th consecutive deficit for the Commonwealth budget. Deficits have averaged $33.2 billion (2.1% of GDP) over those 11 years.

Yes, a $4.1 billion surplus is forecast for next year, with surpluses projected to reach $19 billion (0.9% of GDP) by 2021-22. But so big have the recent deficits been, that even if everything goes well and the fiscal position continues to improve, the budget would need to be in surplus for decades to produce a surplus on average over each year, far longer than what most economists consider a typical economic cycle.

A related fiscal target is that budget surpluses will build to at least 1% of GDP as soon as possible. Despite revenue windfalls from income and company taxes (discussed below), the government is still forecasting it won’t reach that 1% of GDP surplus target until 2025-26. Policy decisions in this year’s budget and MYEFO – including income and company tax cuts, additional funding for independent and Catholic schools, and changes to the GST formula to placate Western Australia – have weakened the bottom line in 2021-22 by $10.5 billion. Hardly the actions of a government in a hurry to deliver a sizeable surplus.

Verdict: Fail.

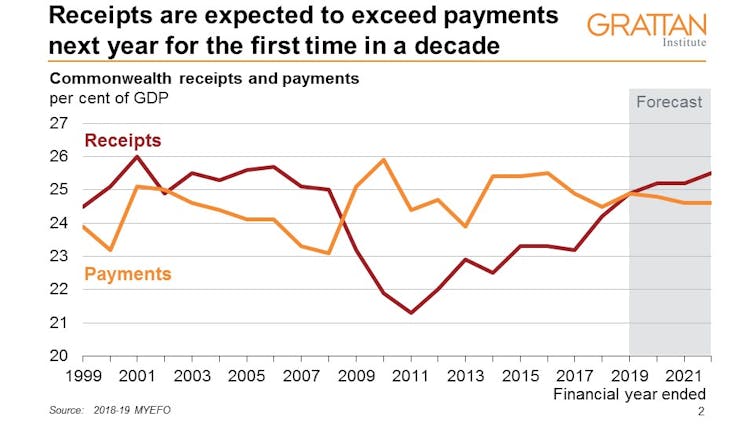

Target 2: Reduce the payments-to-GDP ratio

The government’s policy is also to maintain strong fiscal discipline by controlling expenditure, with a falling payments-to-GDP ratio its measure of success. Whether it has met the target depends on the starting year. Governments payments are forecast to reach 24.9% of GDP in 2018-19, up from 23.9% in 2012-13 before the Coalition took office. The government prefers the starting point of its first year in office 2013-14 where payments were 25.5% of GDP. Either way, payments in 2018-19 remain above the 30-year historical average of 24.7% of GDP.

While the government projects that spending will fall slightly further to 24.6% of GDP by 2021-22, this relies on spending growth across the government’s major programs falling substantially compared to the previous four years – without major policy changes to help facilitate the fall.

Verdict: Debateable pass.

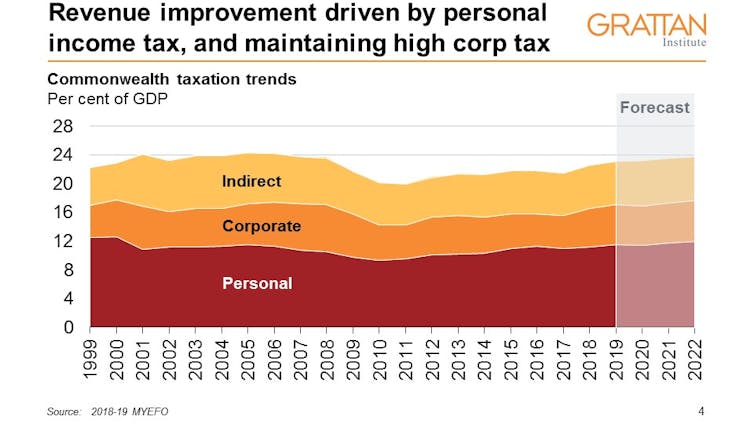

Target 3: Tax-to-GDP ratio below 23.9% of GDP

In last year’s budget, the government introduced a new target of capping tax collections at 23.9% of GDP. Why 23.9%? That was the average level of tax during the final two terms of the Howard/Costello government. While the Coalition is understandably keen to follow the lead of one of its most electorally successful governments, that was also a period where tax collections were historically high.

Tax collections are projected to reach 23.8% of GDP in 2022, on the back of stronger than forecast personal income tax and company tax receipts.

Verdict: Pass.

Target 4: New spending measures more than offset by reductions in spending elsewhere

Since becoming prime minister, Scott Morrison has sent mixed signals about whether his government will adhere to the longstanding budget rule that all new spending proposals be matched with budget savings. At the MYEFO press conference, Finance Minister Matthias Cormann said it was a “matter of balancing competition priorities”. Here’s the straight answer – the net effect of policy changes announced in MYEFO are an additional $12.2 billion in spending over four years. In other words, the government has not offset new spending with cuts to other spending programs. The Turnbull government similarly failed to offset its new spending in 2017-18 (although it succeeded in prior years).

There have been some reductions in spending because of improvements in the economy. The government claims these reductions offset its recent spending announcements. But genuine offsets come from policy changes, not economic good luck.

Verdict: Fail.

Target 5: Shifts due to changes in the economy banked as an improvement in budget bottom line

This objective is key to the government’s fiscal conservative credentials. If it has some economic good luck, it commits to use the proceeds for budget repair rather than new spending or tax cuts.

This rule has been irrelevant for most of the past decade, because almost every budget had revenue collections falling short of forecast. But the Morrison government is in the middle of a mini revenue boom – revenue collections were higher than forecast in both the 2018-19 budget and MYEFO. Company tax collections are higher largely due to strong commodity prices. Income tax collections are up and government spending is down because of improvements in the economy.

So has the government used this chance to show off its fiscal prudence? Not exactly. It will spend around $11.8 billion of this windfall, give away another $19.3 billion in tax cuts and bank just over half of it ($35.2 billion) to the bottom line. And in the shadow of an election, we can almost certainly expect further spending. The $9 billion in decisions taken but not announced – potentially a pre-election warchest – suggests that more tax cuts could also be on the way.

Verdict: Fail.

Our final verdict

The challenge in assessing budget management is separating good luck from good management. Governments will always seek to take credit for economic upswings that boost the bottom line. Fiscal targets are there to keep them on the straight and narrow. An objective assessment of the government’s performance against its own key targets suggests its good news budget is more mirage than magnificent management.