Pointers for improving primary healthcare

by Peter Breadon

When you’re searching for good health policy, America is often the last place to look. But a new way to fund primary care being rolled out there looks promising. It is a long-term commitment, it makes funding more flexible, and it will boost clinics’ ability to provide integrated healthcare. It also targets the social needs that are such big drivers of poor health.

All these ingredients should be part of Australia’s MyMedicare funding changes, which will be designed over the next year.

MyMedicare is one of the building blocks of primary care reform funded in the May federal Budget. Clinics and patients can choose to sign up. If they do, patients will be registered to a practice that will give them ongoing care. In return, clinics will get access to Medicare Benefits Schedule payments for services such as longer telehealth calls and aged care visits.

In the future, participating clinics will also get access to a new ‘blended’ funding model to care for people with complex, chronic disease who frequently go to hospital. The ‘blend’ refers to a mix of flexible, lump-sum budgets for each patient, and ‘fee-for-service’ payments for each visit.

Today, the vast bulk of general practice funding is paid on a fee-for-service basis, with GPs paid for each service they provide. The shorter the patient visit, the better the GP’s pay. It worked well when the system was designed half a century ago, but today the population is older and sicker, and more people need ongoing support to manage their health.

That means the way we pay GPs is past its used-by date. It blocks team-based care, which is the best way to help patients with complex chronic disease. It keeps a lid on the length of GP visits, which have been stuck for years at an average of about 15 minutes. GPs with sicker patients aren’t paid more, and they get little financial reward for taking care of a patient between visits, or over the long term.

MyMedicare will see Australia join many other countries by introducing a blended funding model, but it will not start until 2024-25.

That gives the Health Department time to work with providers and patients to design the approach, and an opportunity to learn from what’s happening around the world, including in the US.

What can we learn from new US reforms?

America’s health system is notoriously wasteful and unfair, and very different to our own. But last month a new primary care funding model was announced that has been welcomed by a range of American doctors’ organisations.

Many aspects of the program align with reforms in other countries, as well as Grattan Institute research on primary care reform, and advice to Federal Health Minister Mark Butler from his expert Taskforce.

The US program, called Making Care Primary, will shift funding from fee-for-service towards patient budgets. It will support clinics to manage chronic disease well, and to join up care with other services.

Change takes time and effort

Making Care Primary will run for 10.5 years. Time is crucial for success.

Australia has had four national trials of primary care reform since the 1990s, each of which lasted for between two and four years. That gives clinics too little certainty to invest in real change, and too little time to test and adopt new ways of working. And it leaves to little time to uncover and fix inevitable kinks in the funding model.

One finding from the damning review of Australia’s most recent big attempt at primary care reform was that there was too little support to help clinics change.

Compared to previous reform attempts in the US, Making Care Primary will do more to help clinics improve in areas ranging from IT systems, to workflows, and working with other teams beyond the clinic.

Practices are different

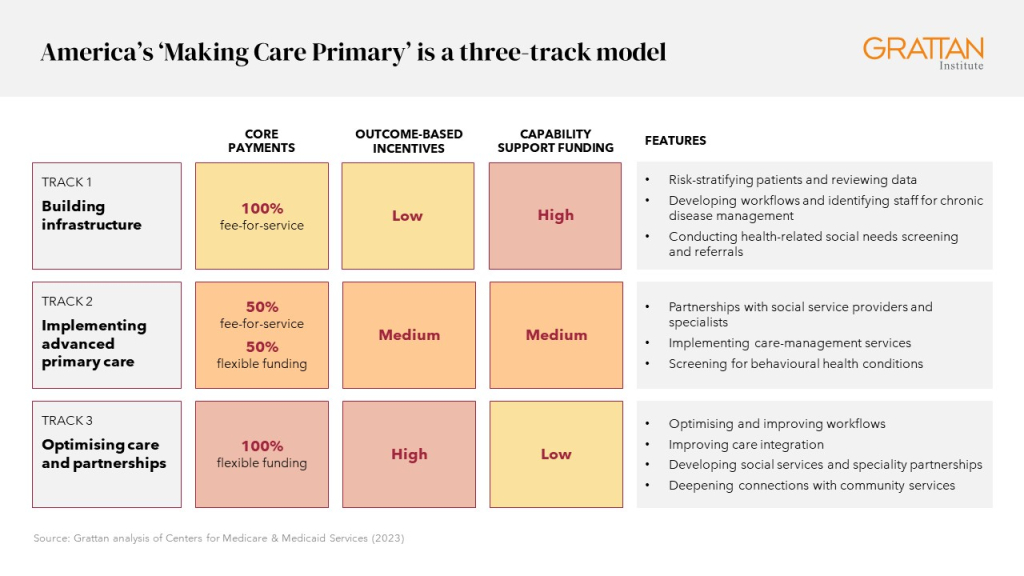

That support won’t be one-size-fits-all. Instead, there will be three ‘tracks’ for clinics, depending on how well prepared they are to provide integrated care, with clinics able to develop and graduate to the next track over time.

Clinics in Track 1 will get support to develop foundational care coordination processes. These include grouping patients by their level of risk, using data to plan and review care, allocating staff to chronic disease management, and identifying and referring patients with social needs. These clinics will keep fee-for-service payments and get financial bonuses for improving health outcomes.

The next two tracks require greater integration of different types of care, and partnerships to address social needs. As the requirements increase, funding changes, with more funding made up of flexible patient budgets and bonuses for improving health outcomes.

Moving from fee-for-service to managing patient budgets is a big change. It requires predicting how much care a patient will need, helping them stay healthy, and avoiding spending too much too often.

One flaw in Australia’s most recent attempt at major primary care reform was assuming that all practices would be able to do this, and not being clear about the skills and systems that clinics would need.

This time around, like the approach being taken in the US, MyMedicare should ensure that participating practices have the right systems and processes in place. The capabilities needed should be made clear, and the clinics that need to change the most should get the most help.

Patient budgets should be big enough to make a difference

Many countries have blended funding models for primary care, but the blend varies a lot.

Flexible patient budgets make up about three-quarters of primary care clinic funding in Denmark, and in Quebec and British Columbia in Canada. In the UK, New Zealand, Italy, Norway, and Sweden, it is closer to one-quarter. Within countries, there is often a menu of options, enabling clinics to opt for higher patient payments and lower visit fees.

Grattan Institute’s 2022 report on primary care reform, A new Medicare, recommended that patient budgets make up 70 percent of funding in Australia. The US model goes a bit further. The minimum level for patient budgets is half of all funding, but it rises to all funding for the most advanced clinics.

Patient budgets are supposed to give clinics the flexibility to plan care, provide it in new ways, and deliver it with a multidisciplinary team.

But if those budgets are too small, they simply won’t give clinics the resources to make it work. Small incentive payments would be a mistake. To support real change, the new type of funding – patient budgets – should be at least 50 percent of the total, as in Making Care Primary.

Equity is essential

The differences in health outcomes between income, regional, and ethnic groups in the US are appalling. Making Care Primary, like funding in other countries such as New Zealand and Canada, will adjust funding so that budgets are bigger for patients with greater health and social risks. For patients with greater needs, there will be more flexibility if a clinic spends more than the patient’s allocated budget.

And the focus on equity goes beyond funding. Each clinic must develop a plan to identify and reduce health disparities. Clinics will be required to assess health-related social needs, such as housing and nutrition, and refer patients to the services they need. More data will also be collected on the social factors that drive patients’ health outcomes, to help guide improvement.

Australia compares well to the US on measures of health equity, but we still need to do much better. There are stark gaps here in life expectancy between people who live in cities and those who live in rural areas, and between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Compared to the most advantaged fifth of Australians, the most disadvantaged fifth are twice as likely to live with two or more chronic diseases, and more than twice as likely to die from avoidable causes.

That’s why MyMedicare should pay more for patients with bigger social and health risk factors, and should encourage clinics to tackle the underlying social drivers of poor health.

MyMedicare is long overdue and Australia should learn from countries that have moved faster.

The policy makers crafting MyMedicare should be studying developments in the US and around the world, to help make sure MyMedicare succeeds where previous primary healthcare reform efforts have failed.

Peter Breadon

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO