Shingles vaccines might come with a bonus

by Peter Breadon

As has been widely reported in the media, a recent study published in Nature found that people who were vaccinated for shingles were much less likely to develop dementia.

While the findings leave many questions unanswered, they are a reminder that Australia should address our low shingles vaccination rates.

The researchers took advantage of a natural experiment in Wales. From 2013, people 79 or younger could get the vaccine, whereas people who were 80 or older would never become eligible.

The academics compared people whose birthdays were within a week either side of the cut-off, 2 September 1933 – two groups that were only slightly different in age, but with very different rates of vaccination.

The health of the two groups could then be compared over time. Years later, a big difference emerged: the vaccinated group were 20 percent less likely to develop dementia.

Protection from dementia could be coming from avoided or less-severe infections, or from increased immune system stimulation, or both.

These latest findings about dementia – which follow several observational studies suggesting an association between shingles vaccination and a reduced dementia risk – aren’t definitive. The researchers stressed that broader confirmation of their findings is critical.

But there are plenty of other reasons to get a shingles vaccine: it protects against the painful rashes and potential nerve damage that shingles can cause. In rare cases, the disease can even cause blindness.

Inequities

In Australia, shingles vaccinations are recommended and free for people older than 65, for First Nations people over 50, and for some younger people who are at increased risk. If it also helps protect against dementia, it makes a good vaccine even better.

But Grattan Institute research has shown that the uptake of shingles vaccines across Australia is troublingly low, with less than half of people in their 70s protected. And the rates for some communities are much lower.

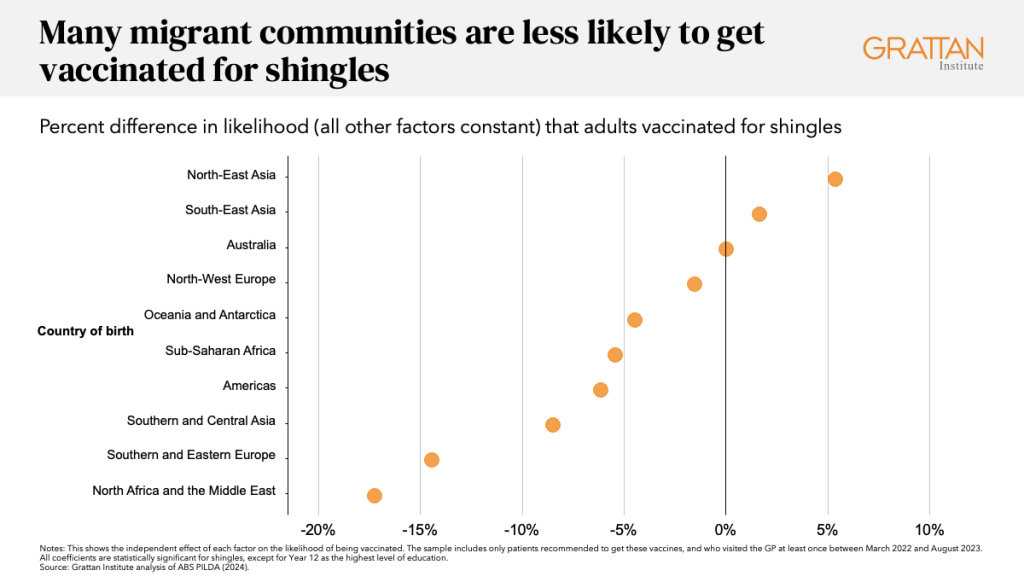

There are big differences between cultural groups.

After adjusting for age, wealth, education, and a range of other factors, people born in North Africa and the Middle East are 17 percent less likely to be vaccinated. If you speak a language other than English at home, you’re eight percent less likely to be vaccinated.

And as with so many types of healthcare, people who are poorer, less educated, and living in regional and rural areas are more likely to miss out.

Variation in practice

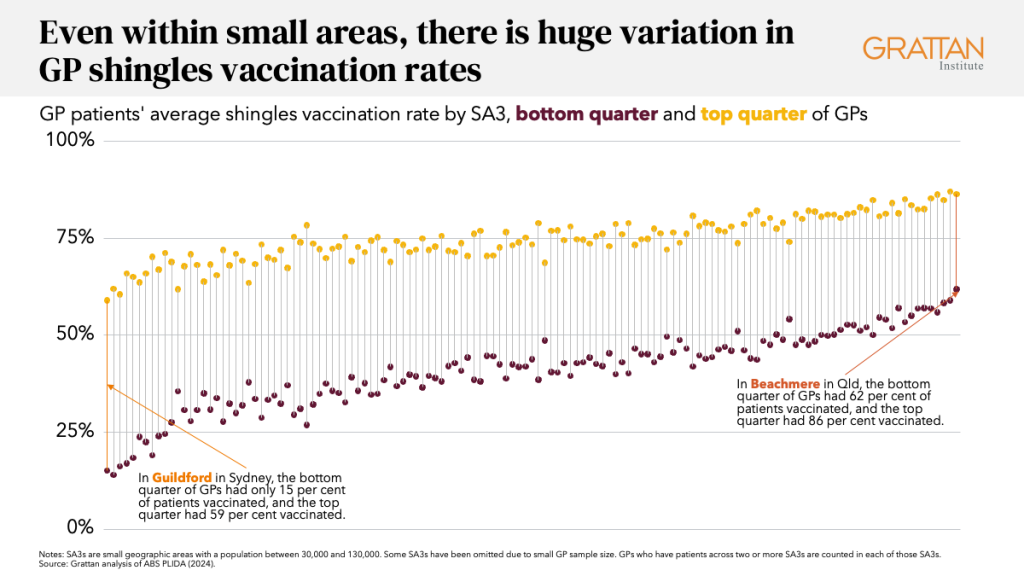

We also found that your chance of being vaccinated varies based on who your GP is.

The best-performing five percent of GPs vaccinate 85 percent of their eligible patients for shingles.

But the bottom five percent of GPs vaccinate only 22 percent of their eligible patients – almost a four-fold difference.

Some of the difference is because of GPs having different types of patients, with different cultural, social, and economic backgrounds.

But there are striking differences even among GPs with similar patients, and among GPs who work in the same area.

In Guilford in Sydney, which has the lowest rate of shingles vaccination, the top quarter of GPs vaccinate 59 percent of their eligible patients, but the bottom quarter vaccinate only 15 percent.

That gap of 44 percentage points is large, but there are areas where the gap is even bigger, and nowhere in Australia is it smaller than 20 percentage points.

Action needed

A national vaccination strategy will soon be released, and it’s an opportunity for a much-needed vaccination policy reset.

The rising threat of misinformation is illustrated by shocking developments in the United States. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Junior, a vocal vaccine sceptic, has downplayed a deadly measles outbreak, promoted unproven treatments, and sacked public health workers.

Our situation may not be as dire, but low and unfair shingles vaccination rates are just one part of a growing problem in Australia. Child vaccination is falling, around one in 20 parents don’t think vaccines work, and aged care vaccination rates remain a scandal.

To overcome these challenges, governments should set targets for adult vaccination, including shingles, to motivate progress. To achieve those targets, the strategy should tackle three levels of vaccination barriers.

For people with low barriers to vaccination, who may just not know what jabs they need, there should be public information campaigns, SMS reminders, and winter vaccination surges.

To help people who need extra support from a healthcare professional to get a jab, governments should galvanise primary care providers. Primary Health Networks should provide data insights, training, and language translation support to GPs, and let GPs know if their vaccination rates are low.

And for local communities, where misinformation and suspicion are holding people back, there should be tailored local programs to overcome those barriers, like those that worked during the COVID pandemic.

The latest findings about dementia are one more reason to be grateful for the underrated medical miracle of vaccination, and to make sure everyone can benefit from it.