Published at The Conversation, Friday 16 May 2014

It was only seven years ago, but it seems like a lifetime; then-opposition leader Kevin Rudd was promising to end the “blame game” in health-care funding.

Fast forward a few years, he’d received a report from the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission and embarked on a disorganised caravanserai around Australia to work out his next steps. To cut the long story that followed short, his proposals didn’t fly.

But former prime minister Julia Gillard was able to negotiate a deal with the states which stuck. Or so we thought. Now, this week’s budget has reneged on the deal.

Adding some dignity

The Gillard deal was enshrined in the National Health Reform Agreement signed by all states and territories (and the Commonwealth) in 2011. It changed hospital funding arrangements in profound ways.

Hospital funding by the Commonwealth used to be based on weighted population (recognising that older people use more health care than younger people), CPI and a “betterment factor” of around 2% per annum to take account of the fact that hospital admissions grow faster than the population.

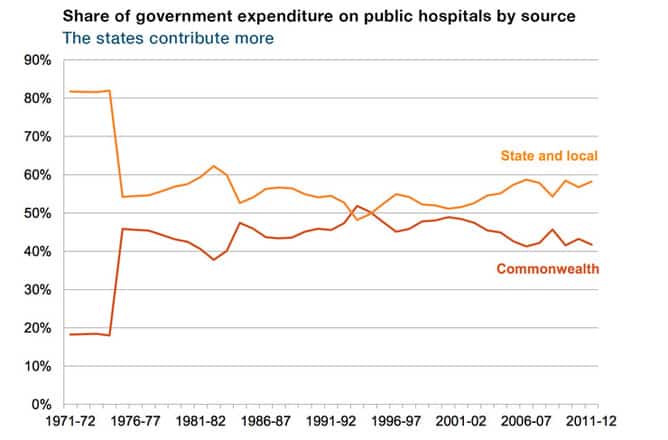

So, prior to the agreement, it was insulated from the cost impact of changing patterns of hospital care. Indeed, since the early 1990s, the Commonwealth’s share of government funding of public hospitals had eroded from just over 50% to 40%.

The states contribute more to public hospitals than the Commonwealth.

Under the old system of periodic health-care agreements, there was an undignified public stoush (aka “negotiation”) at renewal time, which usually resulted in a slight uptick in the Commonwealth share. But the general pattern was still a steady decline in its share.

The Gillard solution had two main components. First, the Commonwealth would share the costs of growth, paying for 45% of new costs in the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2017 and 50% of new costs thereafter.

Second, the costs to be met by the Commonwealth would be based on an efficient level of costs, as measured using a “national efficient price” of caredetermined by an independent body.

Other elements of the deal (and previous deals negotiated by Rudd when he was prime minister) poured substantial funds into hospitals to fix problems, such as long waiting times for elective procedures, and to facilitate other system reforms.

But the current government condemns the rapid growth in Commonwealth funding of hospitals in the last few years as if it were uncontrolled, rather than the result of specific, purposive policy initiatives.

The states’ options

The new Gillard-negotiated scheme will start in six weeks (July 1). Under the budget announcements, it will last for three years and the clock will then be turned back to a CPI plus population, with no mention so far of a betterment factor.

All the states are moving in the opposite direction by linking hospital funding to the average cost of care instead of mindlessly ratcheting it up in line with inflation. The budget changes will save the Commonwealth over $1 billion a year, at the cost of a substantial breach of faith with their Coalition (and occasional Labor) colleagues in state government.

The states have three options to address the funding shortfall:

- look for more revenue to fill the gap – increasing or broadening the GST is one option, as is creating a state income tax;

- look for efficiencies – there’s certainly scope to improve the efficiency of public hospital care but, unfortunately, the places for efficiency gains don’t necessarily line up with where the revenue losses occur and the savings won’t be sufficient to meet costs of future demand growth; or

- allow services to get worse – waiting times for admission or in the emergency department could increase, states could attempt to shift the blame for this onto the Commonwealth but patients would suffer.

Under the arrangements the government is scrapping, both the Commonwealth and state governments have a common interest in controlling hospital cost and admission growth. This gives the Commonwealth, which controls policy for primary care, a direct financial stake in getting primary care to reduce potentially preventable hospital admissions. That’s now gone.

Reopening old wounds

Turning full circle on public hospital funding will reopen old wounds. The blame game will be back, with states attempting to shift responsibility for public hospital deficiencies to Commonwealth parsimony.

The budget changes are clearly a retrograde step. Funding incentives that had been brought into alignment are now out of kilter. An agreed, equitable and efficient cost-sharing arrangement, which should have ended the blame game, has been dumped.

Conservative and Labor premiers alike are crying foul, and legitimately so. And their cries of outrage will probably fall on deaf ears.

But something good could still come out of this budget. It has completely evaded the big question of how Australia should fund health care. But if we all work at it, maybe the shouting match between the Commonwealth and the states can stimulate a meaningful discussion about real, long-term solutions.

In the meantime, even if it rips money out of the state system, the Commonwealth government should rethink dumping efficient hospital funding. Its decision means a big chunk of hospital funding will go back to being arbitrary. But governments need a rational way to set an efficient price, which is perhaps their most powerful tool to control costs.

If it wants to find savings, the government could keep the emphasis on efficiency but reduce the share of activity growth it would meet (subject to some form of negotiations).

In some ways, funding care the wrong way is more insidious than simply cutting funding. In the short-term, it skews the debate away from treating patients and into the murky realm of indexation formulae. And in the long-term, it takes away pressure to keep hospital costs under control.

The federal budget makes the wrong choice: it shifts costs rather than controlling them, and achieves a short-term Commonwealth budget fix at the cost of potentially creating longer-term problems.