Of Australia’s 32 biggest transport projects, just eight had a public business case

by Marion Terrill

Politicians love the vote-pulling power of major transport projects. They also quite like to keep details of how they’ve decided to fund a project under wraps, avoiding the pesky scrutiny the public deserves.

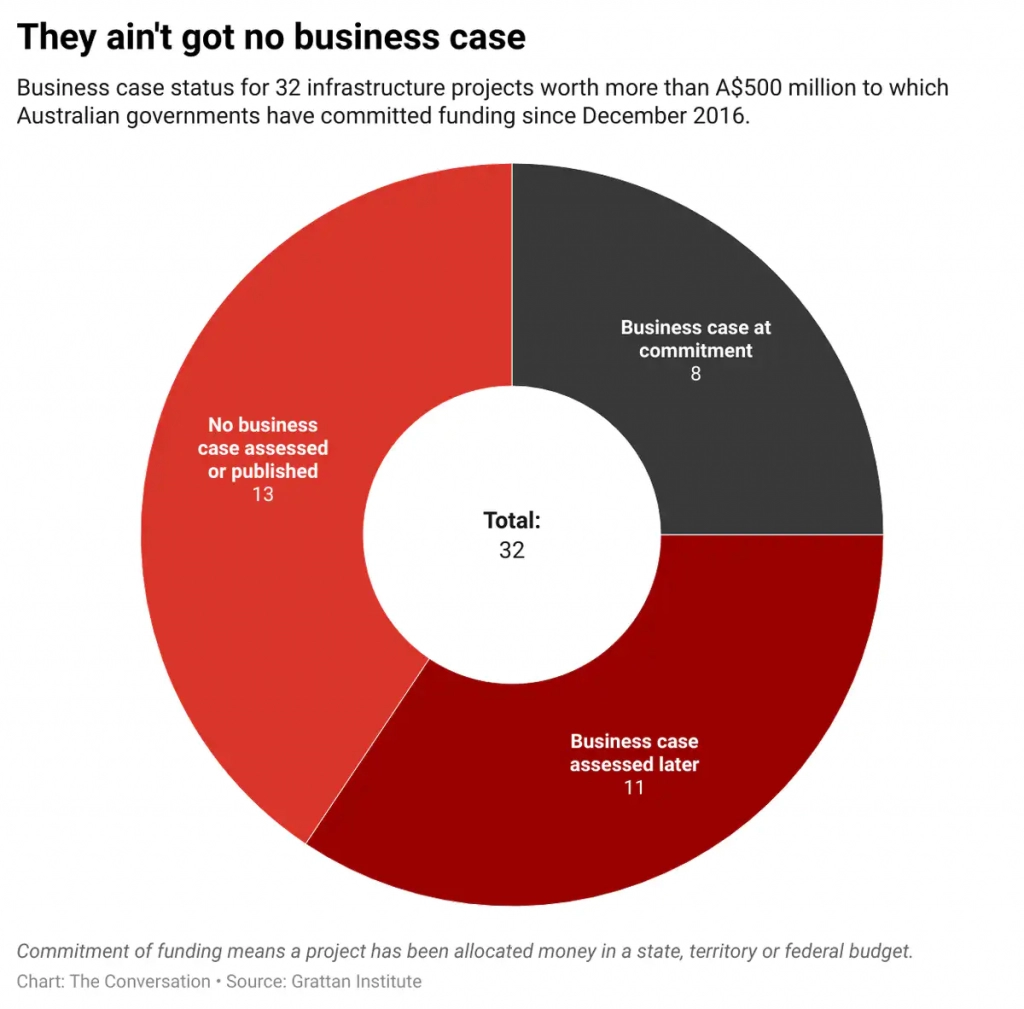

Of 32 projects larger than A$500 million Australian governments have committed to since 2016, the Grattan’s Institute’s analysis shows just eight had a business case either published, or assessed by a relevant infrastructure body at the time money was committed.

A business case documents the essential elements of an argument that a particular project is worth building, and is the best available option to solve a specific problem.

Business cases should be essential to any government considering a large spending commitment. They enable decision makers to establish whether a particular project (or other policy) is a worthwhile investment, and if it is more worthwhile than alternatives. It is reprehensible that federal and state governments so often decide to invest in major projects without publishing such assessments – and often without doing them.

Even the biggest lack business cases

Size is no barrier. There was no published business case at the time of commitment even for the biggest $5 billion-plus projects, such as the 24 km Sydney Metro West rail tunnel between Sydney’s CBD and Parramatta, the Melbourne Airport Rail and the 10 km Torrens-to-Darlington section of Adelaide’s North South Corridor.

This means politicians committed to these projects without being willing to share – or even without knowing – if those projects are in the community’s interest to build, let alone if they are the best choice for the money.

Most of these 32 projects received federal as well as state funding.

Of the 22 large projects to which the federal government has committed a contribution since 2016, just six had a business case published or assessed by Infrastructure Australia, the federal agency established in 2008 to provide independent advice to governments on infrastructure.

Of the 16 projects without business cases, 14 were listed as “initiatives” on Infrastructure Australia’s priority list, indicating they had “the potential to address a nationally significant problem or opportunity”. But their assessment had not yet been completed when committed.

The remaining two projects are Stage 2 of the Monash Freeway Upgrade in south-east Melbourne, and the Albion Park Bypass on NSW’s Princes Highway, south of Wollongong. These two projects, worth more A$2 billion between them, had not appeared on any Infrastructure Australia priority list at the time the state governments committed to them.

As Infrastructure Australia put it in a 2018 report on decision-making principles: “Too often we see projects being committed to before a business case has been prepared, a full set of options have been considered, and rigorous analysis of a potential project’s benefits and costs has been undertaken.”

Cases after the facts

It’s true that 11 major transport projects ended up with a business case later on.

Just last month, for example, the Victorian government released the business and investment case for the first stage of its massive Suburban Rail Loop, expected to cost $30 to $34 billion — three years after it announced its commitment to the project.

We’ve also seen business cases after the decision to invest on Stage 1 of Sydney’s F6 motorway, several sections of Queensland’s M1 Pacific motorway, and on Tasmania’s biggest project, the $500 million Bridgewater Bridge across the Derwent River in Hobart.

Too much secrecy

It isn’t just business cases where there is a lack of transparency. Information about tender processes – who bid, who won, by what process, and the contract value – is not routinely published in Australia. Even when it is, it can be hard to find.

The Grattan Institute’s research shows NSW discloses more information than other states, publishing contract and tender information as a matter of routine in a central register. Queensland discloses the least information, and less of what it does publish is available in a central location.

Politicians may defend their secretive practices by pointing out they are elected to make decisions. But even those who you might imagine would be most likely to side with governments in preferring the shadows — those who build and advise the big projects – disagree with this.

In August the Grattan Institute hosted a webinar with two respected representatives of construction companies, Acciona Geotech’s Bede Noonan and McConnell Dowell’s Chris Lock, and an expert legal adviser, Infralegal’s Owen Hayford. All emphatically agreed governments should have and make public business cases – at the very least.

Not only was this a question of public accountability, they argued, but an opportunity to persuade the community of the merits of a proposal, and a chance to bring in more innovative ideas.

They are right. Transparency is not everything, but it is important. Governments should publish it all: business cases, tender documents, contract values, the basis on which claims for major projects are settled, evaluation criteria, post-completion reviews.

Politicians should welcome the scrutiny. In these fractured times, transparency builds trust.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO