Interest rates are about to rise. How worried should you be?

by Brendan Coates, Joey Moloney

When Reserve Bank governor Phil Lowe cut the cash rate to just 0.1 per cent in the early days of the pandemic, and promised to keep it there until 2024, many Australians took him at his word. House prices rose higher than ever, and many people took on unprecedented debts.

Now interest rates are expected to rise, as soon as next week when the Reserve Bank meets.

Inflation is now running at 5.1 per cent, the highest level in more than 20 years. The big four banks expect borrowers will be paying an interest rate of about 5 per cent by the end of next year, up from 3 per cent today. If bond markets are right, borrowers could be paying more than 6 per cent. It’s enough to give recent homebuyers whiplash.

So, how worried should borrowers be as interest rates rise? It depends a lot on when you bought.

Most homeowners who bought before the pandemic don’t have too much to worry about. Rising house prices and stagnant incomes mean loans are larger – relative to incomes – than they were during previous eras when rates rose. But most borrowers’ interest payments will probably just revert to where they were before the pandemic-era rate cuts.

Plus, many homeowners have used the past two years to get ahead on their mortgages – making the same repayments even after interest rates fell. The typical homebuyer today is nearly two years ahead on their mortgage repayments, up from just 10 months at the start of the pandemic.

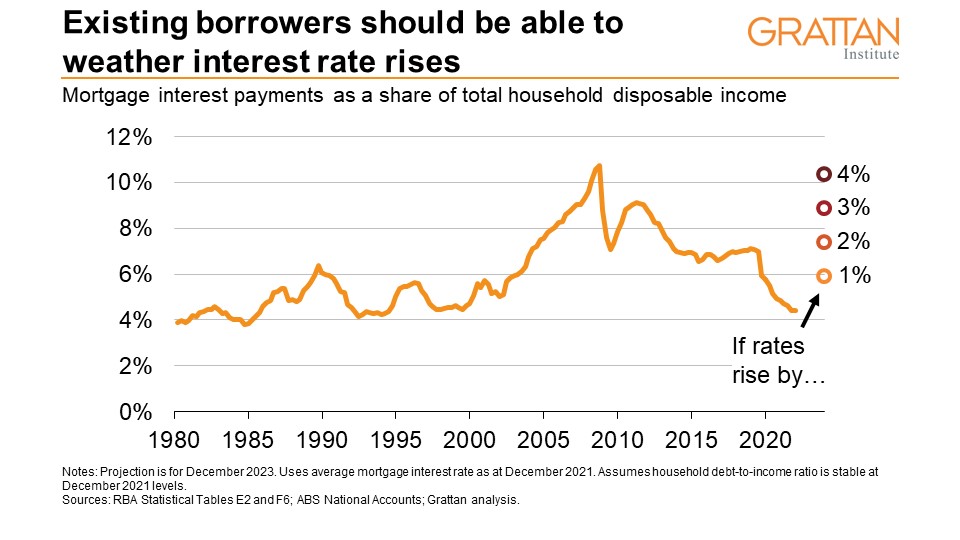

In total, interest payments now comprise just 4 per cent of Australians’ total disposable incomes. If interest rates rise by 2 percentage points, Australians would still be spending less than 8 per cent of their incomes on interest payments – the same level as in June 2019. Interest rates would have to rise by 4 percentage points – to an average mortgage rate of more than 7 per cent – before interest costs would return to the peaks, as share of total household income, that they hit just before the global financial crisis in 2008.

This suggests that higher mortgage rates won’t crimp the spending of most borrowers.

For many Australians, the bigger question is not whether they can afford their mortgage, but what happens to the value of their home as interest rates rise.

The Reserve Bank predicts that a 2 per cent increase in interest rates from current levels would lower house prices by about 15 per cent, undoing most of the rises over the past two years. The long-term impact could be even greater, given many people had expected interest rates to remain lower for longer. Falling house prices result in homeowners feeling poorer. This may reduce their spending by more than the impact of higher interest rates.

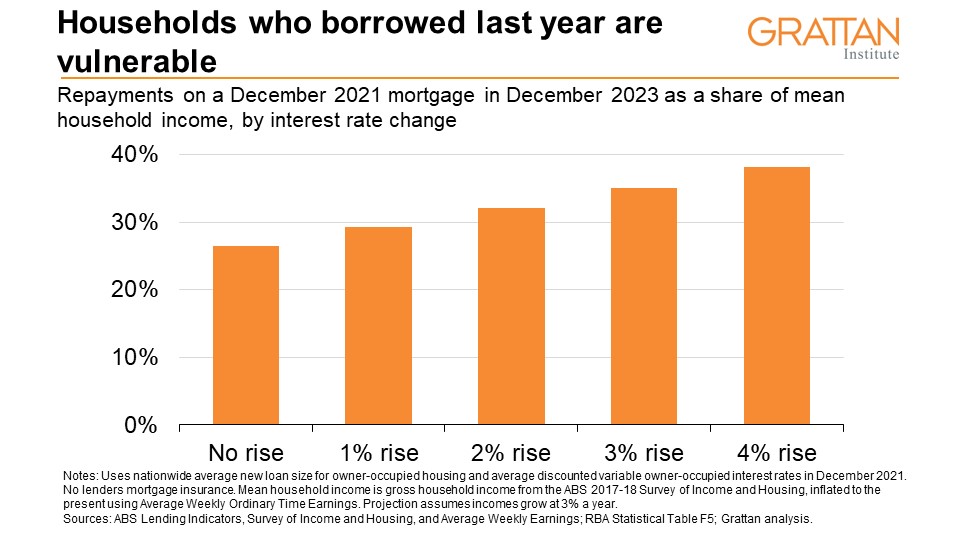

But one group is especially vulnerable to higher interest rates: people who bought a home recently, and borrowed to the max to do so. The average size of new housing loans rose by more than 20 per cent in the past two years alone, peaking at $605,000 in December last year. A quarter of recent new buyers have borrowed more than six times their annual incomes. They face a double-whammy: higher interest rates on big loans. If house prices fall, many of these borrowers will be left with negative equity in their home.

Take the example of a recent homebuyer who took the average loan and earns the average pre-tax household income of $128,000 a year. A 2 per cent rise in their mortgage rate would result in their repayments as a share of their income rising from about 26 per cent to housing-stress territory of 32 per cent. A 3 per cent rise would push them to 35 per cent.

An unexpected fall in income or increases in other expenses could lead them to miss a mortgage payment, increasing their risk of default.

Here’s the bottom line: For most borrowers, the return of higher interest rates won’t cause too much pain. But many recent borrowers will soon be feeling the pinch. And if older borrowers don’t feel much pain, that could encourage the Reserve Bank to raise rates even faster should inflation prove hard to tame.

Brendan Coates

Joey Moloney

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO