Rents are skyrocketing and public anxiety about migration is on the rise. Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has responded by proposing to cut migration.

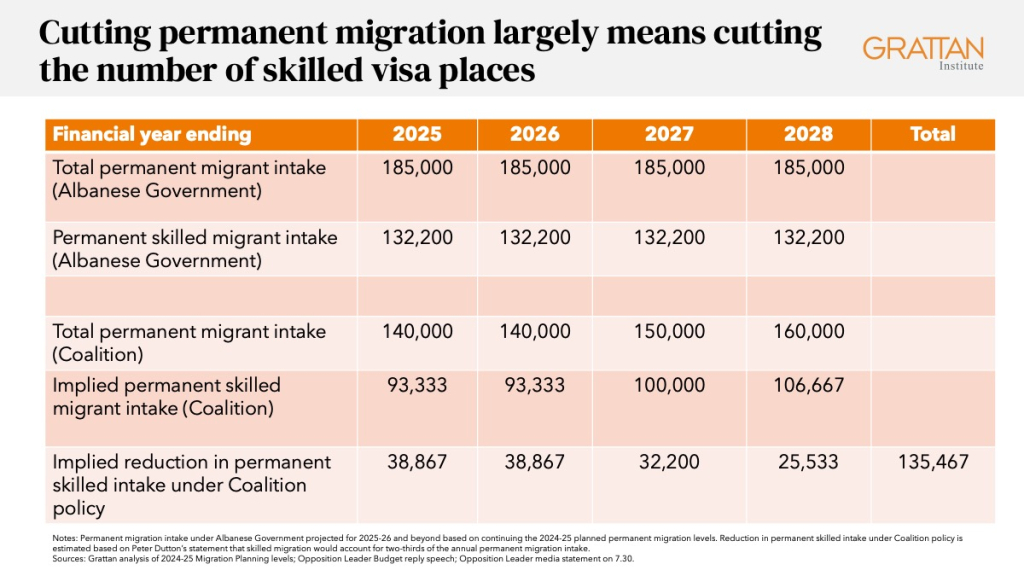

The Opposition plans to lower the number of permanent visas offered each year, from 185,000 to 140,000 for the next two years, 150,000 in 2026-27 and 160,000 per year after that, and to reduce the number of humanitarian visas issued each year from 20,000 to 13,750.

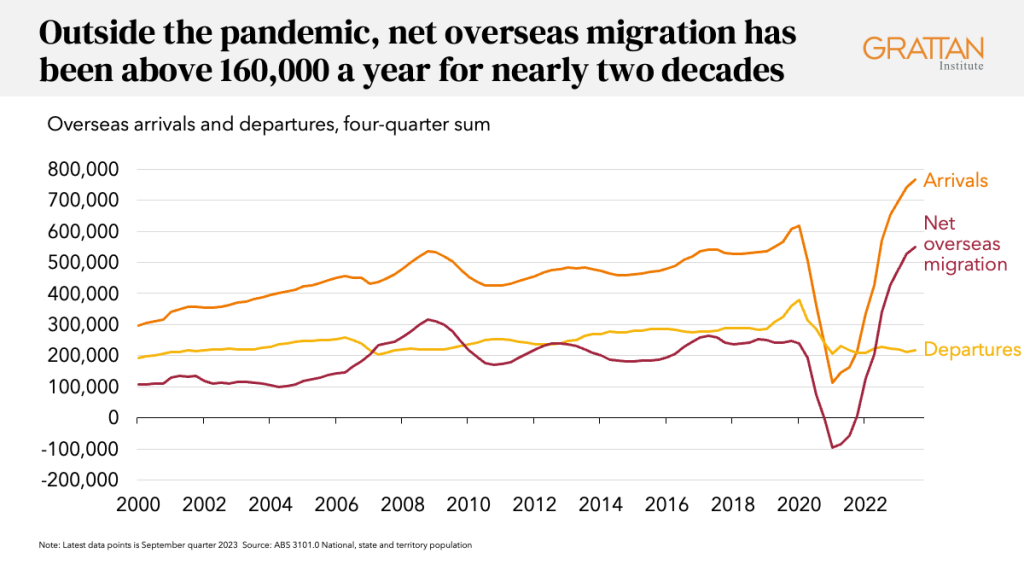

The Opposition has also pledged to reduce net overseas migration, that is, the net gain in population through immigration to Australia and emigration from Australia. The Coalition plans to cut net overseas migration to 160,000 next year, 100,000 lower than the Government’s forecast. And over the next five years, the Coalition plans to reduce net overseas migration by one quarter, compared to the Government’s forecasts.

What would these cuts to migration mean for Australia?

Cutting permanent migration would make housing a bit cheaper

Migrants need somewhere to live, and more than four-in-five migrants settle in capital cities. So, slowing the pace of migration would ease pressure on rents, especially since very few migrants arriving in Australia come with the skills to build the extra homes we need.

But cutting the permanent migrant intake wouldn’t do much to ease demand for housing, at least not straight away. That’s because nearly two thirds of permanent skilled visas go to migrants already in Australia.

The Opposition’s policy to lower the permanent intake to 160,000 a year and cut humanitarian visas would have a bigger impact on Australia’s population in the long term. More temporary visa-holders in Australia would eventually leave, because fewer permanent visas would be on offer. We estimate that cutting permanent visas would, over a decade, would leave rents about 2.5 per cent lower than they otherwise would be.[1]

Cuts to net overseas migration would have a bigger housing impact, but will be harder to achieve

The Coalition’s pledge to cut net overseas migration to 160,000 next year, or nearly 100,000 fewer people than the Government plans, would have a more immediate impact on rents. As would the Coalition’s pledge to lower net overseas migration by 25 per cent on the Government’s levels over five years, which would require net overseas migration to average 190,000 over the following four years. If a Coalition government were to keep net overseas migration at 190,000 permanently, rents and house prices would be about 4 per cent lower than otherwise after a decade. And if net overseas migration were to be cut to 160,000 a year permanently, rents would be about 6 per cent lower after a decade.[2]

But cutting net overseas migration to 160,000 in 2025-26 will be very difficult. The federal government has much less control over net overseas migration, which is affected by uncapped temporary visa programs, as well as the decisions Australians make to move abroad or return home. Outside the COVID years, the lowest rate of net overseas migration recorded in the past decade was 181,000 in the year to March 2015. And net overseas migration hasn’t fallen below 160,000 a year since the mid-2000s.

Pushing net overseas migration down to 160,000, and even 190,000 thereafter, would mean much steeper cuts to international student enrolments, unless the Coalition also plans to tighten other temporary visa programs such as working holidaymakers and temporary sponsored workers.

A Dutton government could also give preference to onshore applicants for the remaining permanent skilled visa intake, to avoid the permanent intake adding further to net overseas migration. But this could mean Australia missing out on the most highly-skilled migrants.

Cutting permanent skilled migration probably means fewer skilled migrants

While fewer migrants would mean cheaper housing, it would also make Australians poorer, especially since it would mean cutting the number of permanent skilled visas offered.

The Opposition Leader has said a Coalition government would aim for skilled migrants to make-up two-thirds of the permanent intake – down from 71 per cent planned for 2024-25. That implies about 135,000 fewer skilled migrants over the next four years alone, compared to the existing plan.

Cutting permanent migration would be a big hit to government budgets

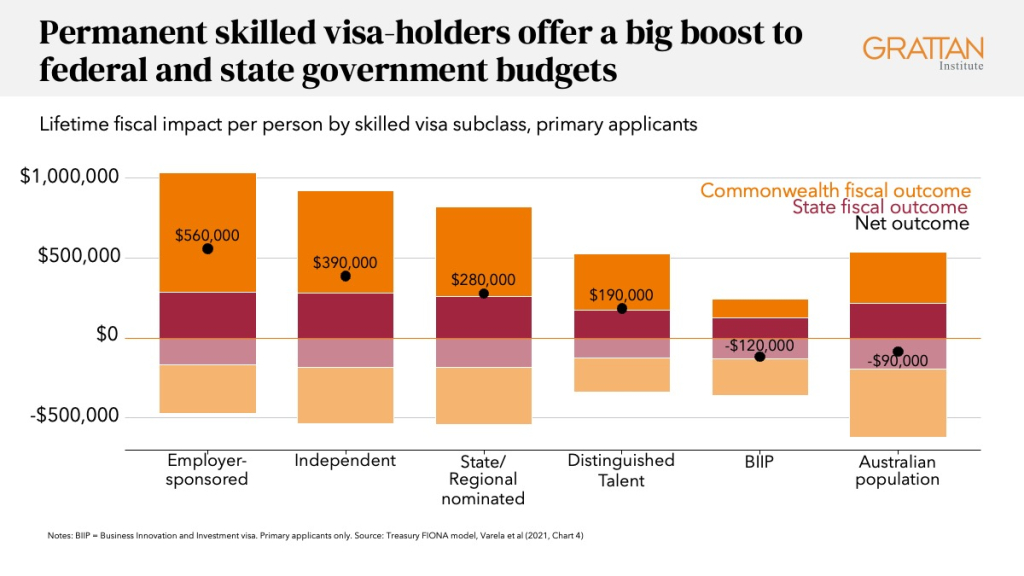

Skilled migrants provide a large boost to government budgets over their lifetimes, because they pay more in taxes than they receive in government services. And that’s after accounting for the budgetary cost of extra spending on infrastructure and services to accommodate a larger Australian population.

Our modelling shows that every permanent skilled visa-holder offers a fiscal dividend to Australian governments of $249,000 (in today’s dollars) over their lifetimes in Australia. Therefore, reducing skilled migration by 135,000 over the next four years alone would cost Australian government budgets $34 billion in lost taxes (net of the services they draw) over those skilled migrants’ lifetimes in Australia.

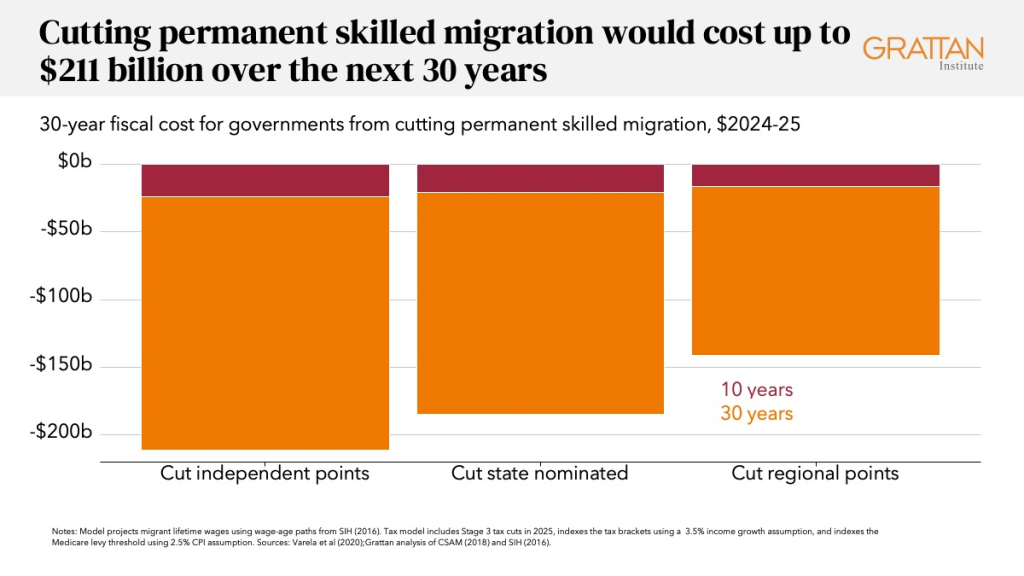

But if permanent migration were to remain at 160,000 a year in the long term, compared to 185,000 intake adopted by the Albanese Government for 2024-25, the long-term costs would be far larger. We estimate that change would cost Australian governments up to $211 billion (in today’s dollars) over the next 30 years, depending on which skilled visas stream was cut.

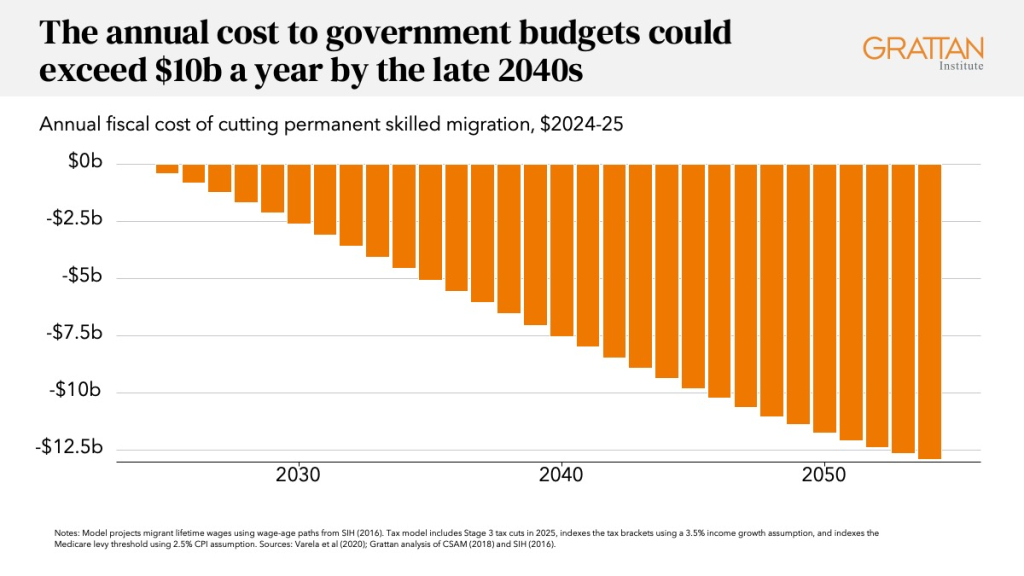

And the annual cost to Australian government budgets from cutting the permanent skilled intake could exceed $10 billion a year by the late 2040s.

Cutting permanent migration would leave Australians poorer in the long term

Cutting the permanent skilled migration program would therefore result in Australians having to pay higher taxes, or get fewer services.

In addition, skilled migrants lift the productivity of incumbent workers, especially through the adoption of new technologies and business practices, and generate the spread of knowledge, which raises incumbents’ incomes. Recent OECD research found that Australian regions with a higher share of migrants tend to have more productive local workers, and that this effect is larger for higher-skilled migrants. On average, a region with a 10 per cent larger migrant share reports wages 1.3 per cent higher. And each 1 per cent rise in the share of university-educated migrants in a region sees patent applications rise by 4.8 per cent over a 5-year period.

But cutting migration is unlikely to have a big impact on skills shortages. That’s because when there are more migrants there are also more jobs. Recent migrants spend more in Australia than they earn, adding as much to labour demand as labour supply. That’s why studies repeatedly find migration has little to no overall impact on the wages of local workers.

Migrants contribute greatly to Australia’s prosperity and shape our diverse society. Skilled migrants in particular lift the productivity of local workers and boost government budgets, raising Australians’ incomes.

Cutting migration, and especially permanent skilled migration, may make our housing a bit cheaper. But it would definitely make us poorer.

Footnotes

- Grattan analysis of ABS Dwelling stock. Assumes a 0.36 per cent increase in quality-adjusted housing stock in response to a 1 per cent increase in housing demand as per Gitelman and Otto (2012, Table 2). Also assumes an average of 3 people per extra home since recent migrants tend to establish larger households on average when they first arrive in Australia. See National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, Box 2.2.

- As per footnote 1.