Why major power blackouts are unlikely

by Alison Reeve

Every year, authorities release a snapshot of how reliable our electricity supply will be in the coming decade. And each time, commentators have divergent takes on what it all means.

So it is with the latest reliability snapshot released by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) on Thursday. Essentially, the report says the national electricity grid – which serves the five eastern states and the ACT – is in a better place than last year. But we’re not out of the woods.

Media coverage interpreted the findings in vastly different ways. Some claimed it was good news for future energy reliability. Others suggested the Albanese government’s renewables strategy had created the risk of power shortages for years to come.

So let’s take a closer look at how the forecast should be understood, and what it means for Australian electricity users.

What has changed since last year?

AEMO manages the nation’s electricity and gas systems and markets. Its annual outlook is known formally as an “electricity statement of opportunities”.

AEMO looks at what’s in the investment pipeline for the next decade, in terms of electricity generation, transmission and storage. It then tests if this combination of assets is able to maintain the reliability of the grid. A potential shortfall is a warning that, without further investment, homes and businesses could suffer electricity shortages.

Last year’s forecast warned of a need for more investment, particularly for transmission lines, to deliver a reliable electricity supply. So what’s changed this time around?

AEMO says the outlook for energy reliability has improved. It pointed to progress on an extra 5.7 gigawatts (GW) of new generation and storage developments since last year. These include:

365 kilometres of transmission connections.

3.9GW of battery storage

1.2GW of large-scale solar

about 400 megawatts (MW) of wind power

The improved forecast also takes account of a two-year extension in the life of the Eraring coal plant in New South Wales and the ongoing rapid increase in rooftop solar capacity. Other projects making progress include a 750MW gas plant in NSW’s Hunter Valley and pumped hydro storage including Snowy 2.0.

In 2023, investment in new large-scale renewable energy slowed, though investment in rooftop solar and large and small batteries remained strong. The government responded by expanding its underwriting program to support large-scale generation projects. This program makes it easier for project proponents to secure financing, by topping up future revenues if they fall below an agreed level.

There’s more good news. The 12GW electricity generation capacity approved last financial year is nearly double the 6.9GW approved the year before.

It’s also worth noting how far Australia has already come in its transition to renewable energy. We’re fast approaching the halfway mark, averaging about 40% renewable generation. Some days, renewables can meet 100% of the demand for electricity.

In 2000, renewables’ share was only 2%. We have seen a huge transformation in just 24 years.

But what could go wrong?

Australia is still heavily reliant on coal-fired power plants, some of which are fast approaching retirement. The next big one due to close is Eraring, the country’s largest, in 2027. Yallourn in Victoria and Callide B in Queensland are due to close in 2028.

The latest forecast assumes the schedule for closures doesn’t change. By 2035, though, AEMO expects 90% of coal capacity to have closed, reducing it from the current 21GW to 1.4GW.

The grid is also facing a rapid rise in electricity consumption in the next decade and beyond. This is a result of the electrification of transport, industry and households. So new generation and transmission must be built to meet this new demand, as well as to replace ageing coal.

AEMO also tests the impacts of all these developments and the inherent uncertainty of events. It does this by modelling project delays and cancellations, power station shutdowns and closures, and changes in demand.

The results of this modelling are presented in its forecasts, according to different scenarios. Often, media outlets pick up on either the most positive or negative of these scenarios, leading to the divergent headlines we’ve seen today.

Insurance against black-outs

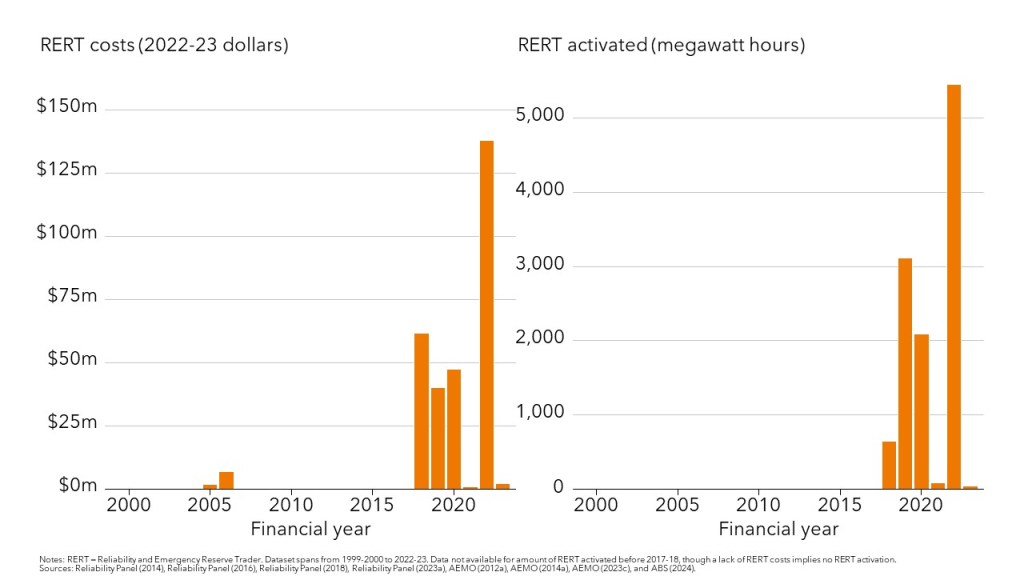

AEMO is taking out a form of insurance against outages this summer by activating the Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (or RERT) mechanism. AEMO will call for tenders for large electricity users, such as aluminium smelters, to agree to power down when the system is under strain, in return for payments. In addition, owners of back-up generators could be paid to turn them on to feed power into the grid if energy demand looks like it might exceed supply.

AEMO has also asked electricity retailers to ensure they have contracts in place for enough supply to meet a one-in-two-year level of peak demand.

Tools like these have been used a lot more often in recent years as the chart below shows.

This suggests the system has been under more stress. It points to the need, as AEMO signalled in last year’s statement, to increase investment in the system.

What does this mean for households?

The statement’s main scenario, the one considered most likely by AEMO, suggests Australia is largely on track for maintaining a stable electricity supply. That’s provided the current pipeline of investment delivers on time and generators aren’t retired early.

The system operates to a very high reliability standard of no more than 10.5 minutes’ interruption to supply across the whole system for the year. The vast majority of outages (97%) are caused by network failures – storms, wind, traffic accidents – rather than lack of generation.

For Australians connected to the national grid, this means it’s still very unlikely their lights will go out in a widespread and prolonged blackout.