We are delighted to announce our Prime Minister’s Summer Reading List for 2024.

Each year, Grattan Institute selects its best books of the past 12 months – recommended reading for the Prime Minister, and indeed all Australians, over the summer holidays.

This year’s list is:

- Näku Dhäruk The Bark Petitions: How the People of Yirrkala Changed the Course of Australian Democracy, by Clare Wright

- Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space, by Adam Higginbotham

- Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World, by J. Doyne Farmer

- Seventy Miles in Hell, by Caitlin Dickerson

- Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI, by Madhumita Murgia

- Only the Astronauts, by Ceridwen Dovey.

It was a rigorous selection process: the Grattan staff book club read, loved, loathed, and debated an extensive array of novels, non-fiction books, essays, and articles.

The six we landed on are all cracking good reads. And they all (well, mostly) have one other thing in common: they put humans squarely in the centre of the frame.

Näku Dhäruk and Challenger are case studies in how a handful of people can shape the course of history, for better or for worse.

Making Sense of Chaos argues that we can glean new insights into the economy by modelling individuals’ behaviour from the ground up.

Seventy Miles in Hell and Code Dependent remind us of the human consequences of our high-level policy choices on migration and AI.

Our last pick, Only the Astronauts, is a little different: it’s a series of vignettes about inanimate space objects. But it too offers a new perspective on the human experience by looking in from the outside.

Here’s why we chose our six books of the year.

Näku Dhäruk The Bark Petitions: How the People of Yirrkala Changed the Course of Australian Democracy

Clare Wright

Historian Clare Wright knows a thing or two about Australian democracy. In The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, she told the story of the Southern Cross flag, challenging the traditional narrative of the Ballarat goldfields as an exclusively male domain. Wright’s You Daughters of Freedom portrayed the Australian-made women’s suffrage banner as a symbol of a young democracy, leading the world by giving women the vote. And now, in this third and final instalment of her Democracy trilogy, Wright describes the creation of Näku Dhäruk (the Yirrkala bark petitions) as a pivotal moment in Indigenous-settler relations. Flag, banner, and bark: physical artefacts of Australian democracy.

The petitions – written in Yolŋu Matha and English, pasted on bark, and framed in ochre designs of animals, plants, and ancestral beings – were presented to Parliament in 1963 and protest against the encroachment of mining onto North-East Arnhem Land. They were the first petitions presented to Parliament in an Australian language and a sophisticated act of diplomacy and statehood. The petitions make several requests, consultation with the Yolŋu land-owners key among them. The requests went unheeded. Some media outlets and MPs even questioned the petitions’ legitimacy.

Wright’s work is a masterclass in storytelling. She draws from an extensive array of primary sources – diaries, notebooks, letters, photographs, oral histories. In particular, readers get to experience the events surrounding the petition through the eyes of Yirrkala superintendent Edgar Wells and his wife Anne Wells, whose private collection Wright is the first person outside the family to view.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart calls for a Makarrata Commission to oversee a process of treaty and truth telling. The truths told in Wright’s Näku Dhäruk make it essential reading for the Prime Minister and the Australian people. If studying history helps us learn from our mistakes, Australia’s dismissal of the bark petitions is a chapter worth poring over.

Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space

Adam Higginbotham

What is an acceptable risk? This is the question that propels Adam Higginbotham’s riveting retelling of story of the Space Shuttle Challenger, which exploded just after take-off on 28 January 1986, killing all seven crew.

Higginbotham starts the story back in the heady days of the 1960s space race, when NASA developed a reputation as the global leader of manned space flight. But that success obscured the huge risks involved in rocketing humans into the unforgiving environment of space – and successfully bringing them home.

As NASA turned its mind toward the Space Shuttle program that was designed to fly into space ‘on an airline schedule’, these risks only continued to mount. Higginbotham charts a litany of failures that contributed to the ultimate disaster, from designs that were compromised to better serve US national security interests, to a sclerotic NASA bureaucracy that strained under the weight of high expectations and ever-shrinking budgets.

At its heart, Challenger is a human story – an exploration of the trials faced by individual NASA engineers and astronauts in their quest to reach space. The frozen rubber O-rings that ultimately led to the disaster were a known problem. But a flawed decision-making process allowed it to become merely one ‘acceptable risk’ among many.

As demands on governments grow even as trust in institutions declines, Higginbotham provides a timely reminder of the role of individual agency in shaping the success or failure of humanity’s greatest endeavours.

Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World

J. Doyne Farmer

What do a dripping tap, an ant colony, and the Global Financial Crisis have in common? According to J. Doyne Farmer, they are all best understood through complex systems science – the study of how simple interactions between many parts leads to chaotic behaviour and unexpected patterns.

In Making Sense of Chaos, Farmer argues that traditional economics fails to grapple with the complexity and uncertainty of real-world economies. He makes the case for complexity economics, a new approach that draws insights from biology, neuroscience, and physics. This framework models the economy from the ground up, simulating the dynamic web of interactions between people, goods, and institutions.

Trained as a physicist, Farmer’s journey into chaos began at the roulette table, where he and his colleagues used Newton’s laws and a tiny computer to beat the odds. Years later, he co-founded Prediction Company, applying statistical forecasting to consistently outperform the stock market – a feat most thought impossible without insider trading.

Since then, Farmer has been a central figure in the growing field of complexity economics, offering a new perspective on sticky questions that traditional methods have long wrestled with. For example, why do markets crash? Farmer and his team showed that treating the stock market as an evolving ecosystem of investors can reveal the feedback loops and tipping points that drive sudden collapses.

These models aren’t just theoretical. Farmer’s team made strikingly accurate predictions about the UK economy during the pandemic, helping the government plan its response. With vast data and computational power now available, complexity economics could be the next testbed for evidence-based policy.

Accessible and thought-provoking, Farmer’s book blends stories from his remarkable career into a comprehensive introduction to the field. Whether you’re new to economics or a seasoned expert, this book will inspire you to embrace a little bit of chaos.

Seventy Miles in Hell

Caitlin Dickerson

Seventy Miles in Hell was written for The Atlantic magazine by Caitlin Dickerson, investigative journalist and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism in 2023.

For this piece, Dickerson travelled the Darién Gap, a dense stretch of jungle between Colombia and Panama known for its extreme terrain, and the only land bridge connecting North and South America.

Thought for centuries to be impassable, given the deadly dangers and absence of even a basic road, it has become a route for thousands of people desperate to reach the US, as the US shuts established routes and denies visas to people from nearby countries.

In contemporary debates, where migration policies are entwined with political positioning, easy scapegoating, and a way for politicians to signal ‘toughness’, migrants are often treated as numbers, inputs into an economy, or worse, rather than as human beings with their own hopes, strengths, and impossible choices.

Dickerson’s extraordinary account shows us what it takes to traverse the Darién Gap, but also gives us a rare look at the people who find themselves on this route. Her first travelling companions are a Venezuelan nurse and engineer, and their two small children, whom they physically carry through the jungle.

Dickerson’s account draws the reader in, compelling you to bear witness to what humans have borne as the result of failed policies. Her writing is crisp, holding you until the end, and the accompanying photographs from Lynsey Addario complete the vivid picture.

Dickerson’s message is clear and should not be ignored despite the politics of the age: ‘What I saw in the jungle confirmed the pattern that has played out elsewhere: The harder migration is, the more cartels and other dangerous groups will profit, and the more migrants will die.’

Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI

Madhumita Murgia

Artificial intelligence is everywhere. It is used by Google Maps to find the quickest route to our destination, it curates the ads we see on Instagram, and it helps children with their homework.

AI is also used for making predictions, such as which children will commit crimes, or which teenagers will fall pregnant.

But as AI is increasingly embedded in our systems and decisions, what does this mean for our society? In Code Dependent, Madhumita Murgia argues that our blindness to AI systems and how they work makes it harder for us to understand when they go wrong or cause harm. And there’s a risk that those harms disproportionately affect marginalised groups.

We meet Helen, a victim of deepfake technologies; Hiba, who is training AI algorithms in Bulgaria; and Karl, an AI model designer. These human stories, and others throughout the book, point to the varied effects of AI technologies across the globe.

We also see the variety of human responses to AI technologies: a sense of powerlessness for some, but for others, a resolve to fight back, reclaim their autonomy and control over their lives.

The questions that policymakers must grapple with are almost as numerous as the possible uses of AI: How do we know if AI technologies are safe, or if they are being manipulated or used in discriminatory ways? Which laws need to be amended to take AI into account? More broadly, who is ultimately responsible when AI technologies cause harm?

Code Dependent is a book for our times – a thought-provoking read for anyone interested in how AI technologies are reshaping the world around us.

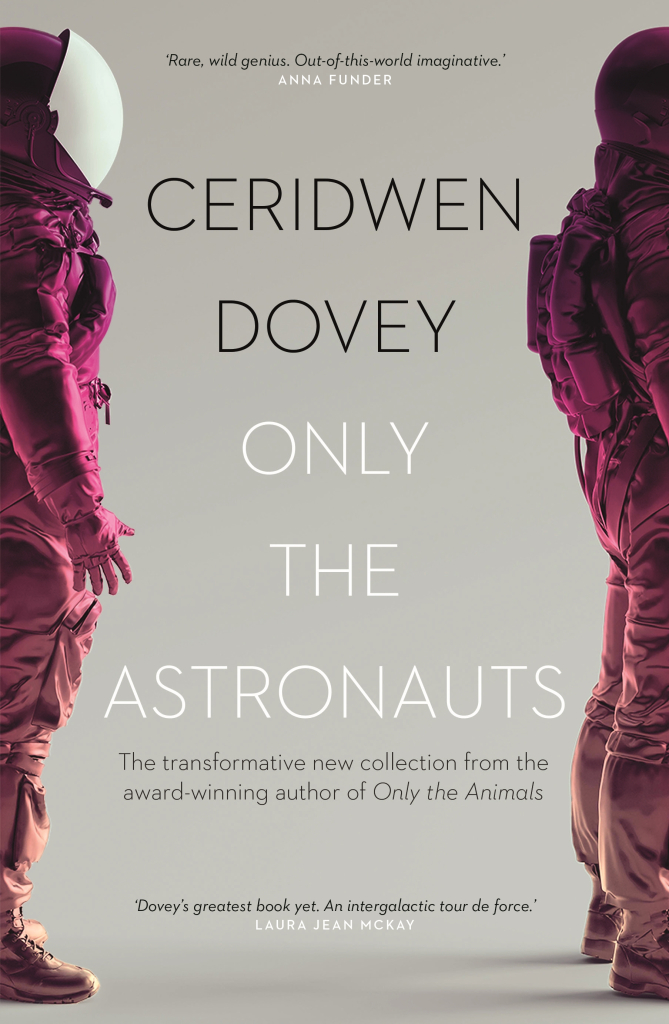

Only the Astronauts

Ceridwen Dovey

Mundane summer chores sapping your spirit? Take a weight off and escape to the cosmos with Ceridwen Dovey’s newly launched book, Only the Astronauts.

The book comprises five short stories, each from the perspective of different space objects, real and imagined (a mannequin set adrift by Elon Musk, a team of tampon-astronauts or ‘tamponauts’).

Dovey, an Australian science writer as well as novelist, shows us humans as they might appear to the objects we create and use.

Like Adam Higginbotham in Challenger, Dovey critiques the masculine bravado of the space race. In one story, an astronaut, watching a comedy in her bed, cries tears of laughter. As they drift up through the vents of the International Space Station, she wonders if her all-male crew of fellow astronauts will mistake them for tears of sadness and think her weak.

In another vignette, Dovey pokes fun at the true story of the all-male engineering team preparing a spaceship for a voyage involving Sally Ride, the first female American astronaut in space. They design space make-up and ponder how many tampons to pack. ‘Will 100 for one week be enough?’ they ask. Dovey brings to life the ‘ancestor’ of one of these hundred tampons, who pens a tongue-in-cheek screenplay in which a group of tamponauts (tampon astronauts) sets off on a perilous mission to Mars. One of the group is a surly menstrual cup, who, despite not being a tampon, calls herself a ‘tamponaut’ out of solidarity.

This inventive collection of stories has moments of beauty, as well as laugh-out-loud fun. It’s perfect for dipping into this summer (even better while dipping your toes in the lapping ocean).