Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 7 November

It’s conventional wisdom that Australians don’t save enough for retirement. Most workers themselves think they won’t have enough to retire on, and their concerns are rising.

But the conventional wisdom is wrong.

Our new report, Money In Retirement: More Than Enough shows that most people who are actually retired feel more comfortable financially than the Australians younger than them who are still working.

Retirees of today tend to slow their spending as they age, tend to keep saving in retirement, and often leave a legacy almost as big as the nest egg they had on the day they retired.

When surveyed today the retirees of the future might be worried about their retirement, but economic growth means they will almost certainly be on even higher incomes than retirees today.

These findings might seem surprising: they contradict the repeated messaging from the financial services industry that Australians won’t have enough for retirement.

But that industry’s claims are based on research that overlooks two important points.

Retirees spend less over time

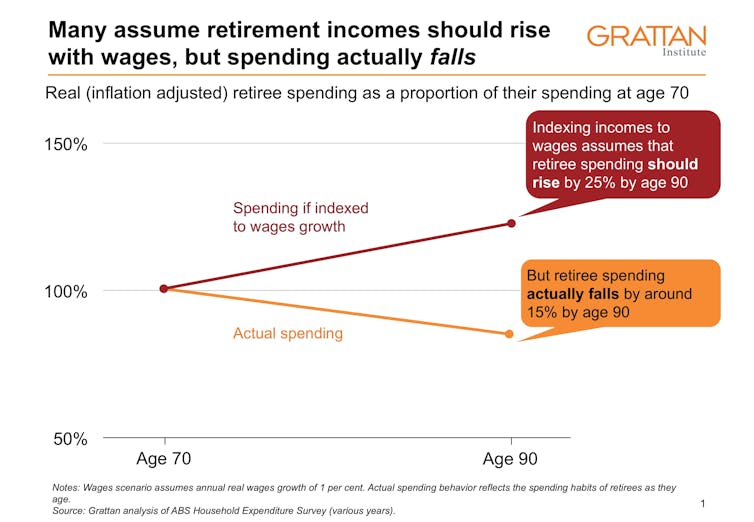

Much of the research assumes that retirees need to save enough to enable their incomes to keep climbing throughout their retirement in line with general wage growth.

Implicitly, it assumes that a retiree needs to spend 25% more at age 90 than at age 70, after accounting for inflation.

But our analysis shows that retired Australians tend to spend less over time, even those who have money to spare.

Young retirees might chalk up frequent flyer points, but they do it less as they get older.

Spending tends to slow at around the age of 70, and falls rapidly after age 80, to just 84% of what was spent at retirement age.

Even the wealthiest retirees spend less as they age. At the other end of the scale, pensioners receive discounts on everything from car registration to rates.

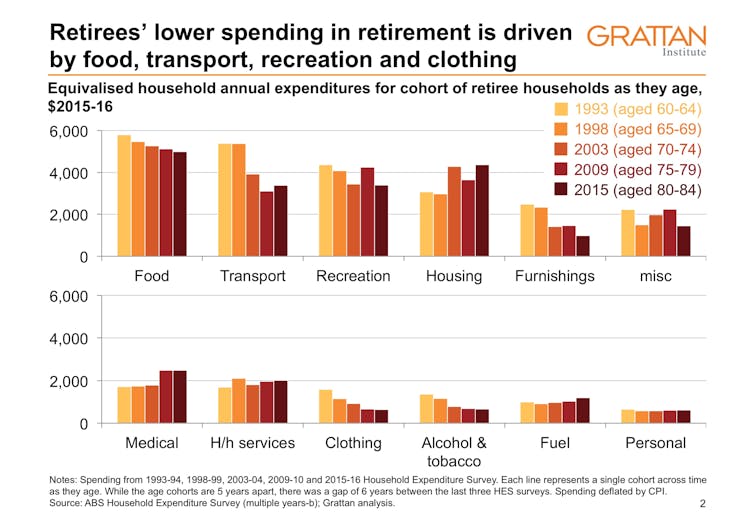

Our research finds that retirees spend less over time on food, alcohol, tobacco, clothes, furnishings, transport and recreation.

They spend more on health care as they age, but Medicare largely shields them from the full costs. The modestly higher out-of-pocket costs they do pay are mainly due to rising premiums for private health insurance.

Not only do most retirees not draw down their savings throughout retirement, many add to them.

Even among pensioners, one recent study found that the median (typical) pensioner still had 90% of what he or she retired on after eight years.

This means that calculations about the adequacy of retirement savings ought to be based on whether they are enough to maintain buying power (at best) rather increase it in line with wage growth.

Many prominent studies also ignore non-super savings, which are material, especially for wealthier households.

They lead to misguided calls for ever-higher super contributions in order to ensure reach the point where super alone is enough to provide an adequate retirement income, even though many households will have income from other sources.

Most will have enough super

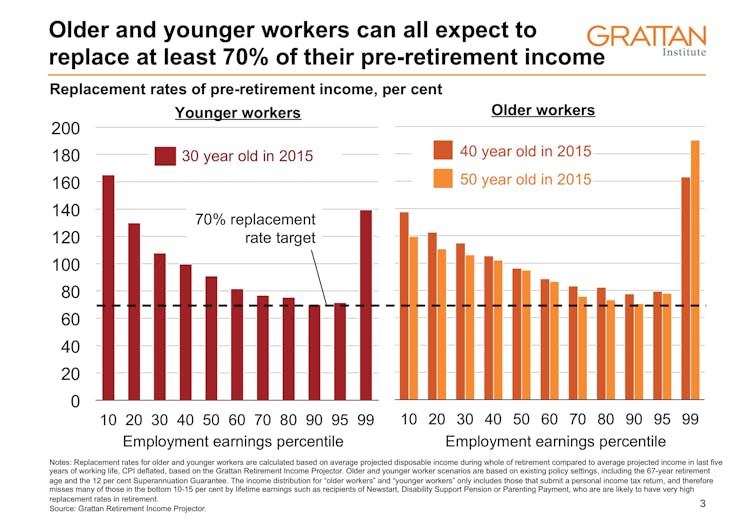

Our modelling shows that people starting work today will have adequate retirement incomes: workers of all income levels will retire on incomes at least 70% of their pre-retirement earnings – the so-called replacement benchmark used by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Mercer Global Pension Index.

In fact the median (typical) worker can expect a retirement income of 91% of his or her pre-retirement income.

This means that many low-income Australians will actually get a pay rise on retirement.

Even workers in their 40s and 50s today – many of whom didn’t benefit from the present high rate of compulsory super contributions for their entire working lives – can expect a retirement income of about 70% of their pre-retirement incomes.

So compulsory super can stay at 9.5%

It means that that there is no obvious case to lift compulsory super contributions from 9.5% to 12% of salary as presently legislated.

Doing so might further boost retirement incomes (especially among those low and middle earners unable to compensate for the higher contributions by winding back other savings), but at the expense of providing lower incomes while working.

As the Henry Tax Review noted, higher compulsory super contributions are ultimately funded by lower wages than would have been the case, meaning lower living standards while in work.

As it happens, higher contributions would do little to change the retirement incomes of low and middle income Australians. Their extra superannuation income they provided would cut their age pension payments.

Higher compulsory contributions would also damage pensions in another way.

The age pension is indexed to wage growth which would be lower if employers diverted a steadily increasing proportion of their employee budget to super.

It means the most fervent opponents of a lift in compulsory super contributions from 9.5% to 12% ought be those people presently on the age pension.

The government ought to oppose it as well. Diverting more of what would have been wages to more lightly taxed super will strain its budget. Scrapping the proposed increase would save it an impressive A$2 billion a year.

We can find better ways to help retirees

Even if governments did feel it necessary to boost retirement incomes, lifting compulsory super contributions would be one of the worst ways to do it.

Loosening the age pension assets test taper could boost retirement incomes of around 20% of retirees, climbing to more than 70% over time. It would cost the Budget just A$750 million a year – less than half the cost to it of the proposed increase in compulsory super.

The real priority – by far the biggest bang for the buck in alleviating poverty in retirement – should be boosting Commonwealth rent assistance by 40%, providing an extra $1,410 a year for retired singles and $1,330 for retired couples.

Senior Australians who rent privately are much more likely to suffer financial stress than homeowners. And renting will become more widespread as younger generations on low incomes find themselves less able to afford homes.

Australians have been told for decades that they’re not saving enough for retirement. Such claims are inconsistent with the facts. Most of today’s workers can already expect a comfortable retirement. Forcing them and future workers to save more money for retirement that they’ll never spend is simply a recipe for larger bequests.