Thank you to Allegra Spender for convening this tax forum today, and for the invitation to speak to on the issue of the tax treatment of superannuation.

It’s easy to see why super tax is back on the agenda.

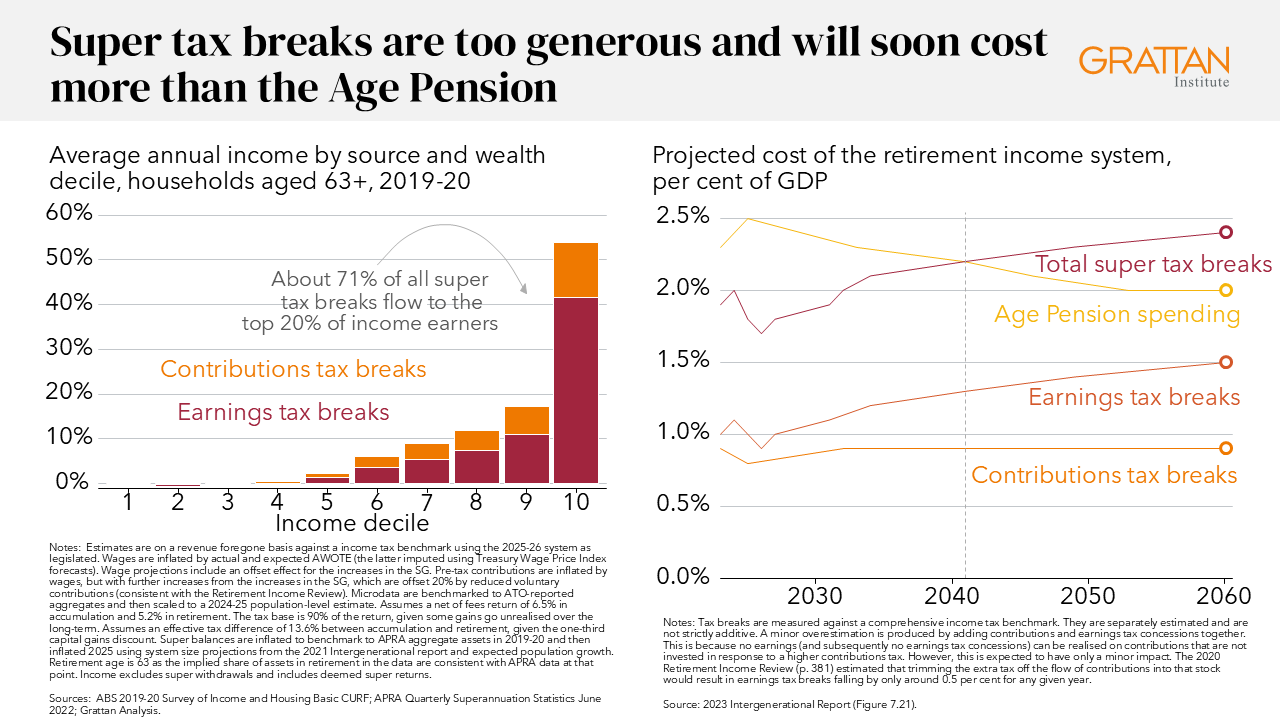

Superannuation contributions and earnings are both taxed more lightly than other income. These tax breaks cost the budget nearly $60 billion a year, or more than 2 per cent of GDP.1$58 billion combined for super contributions and earnings tax breaks as of 2025-26 estimated against a comprehensive income tax benchmark on a revenue gain basis (i.e. adjusted for behavioural change). “Revenue gain” estimates obtained by using revenue foregone estimates in Treasury (2025), Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement, Tables 2.1 and 2.2 and adjusted down reflecting the ratio between the ‘revenue gain’ and ‘revenue foregone’ estimates for super earnings tax breaks last published in Treasury (2022), 2021 Tax Benchmarks and Variations Statement, to generate an updated ‘revenue gain’ estimate 2025-26. Given interactions between separate contributions and earnings tax break estimates, the estimated combined cost of these tax breaks have also been adjusted when combining them here. Callaghan et al (2020, p. 381) estimated that trimming the extra tax off the flow of contributions into the stock would result in the dollar value of earnings tax breaks falling by only about 0.5 per cent for any given year.

Treasury predicts that the cost of these tax breaks will overtake the cost of the Age Pension by around 2040.2Australian Government (2023), Intergenerational Report 2023, Figure 7.21.

More than two-thirds of super tax breaks go to the top 20 per cent of earners.

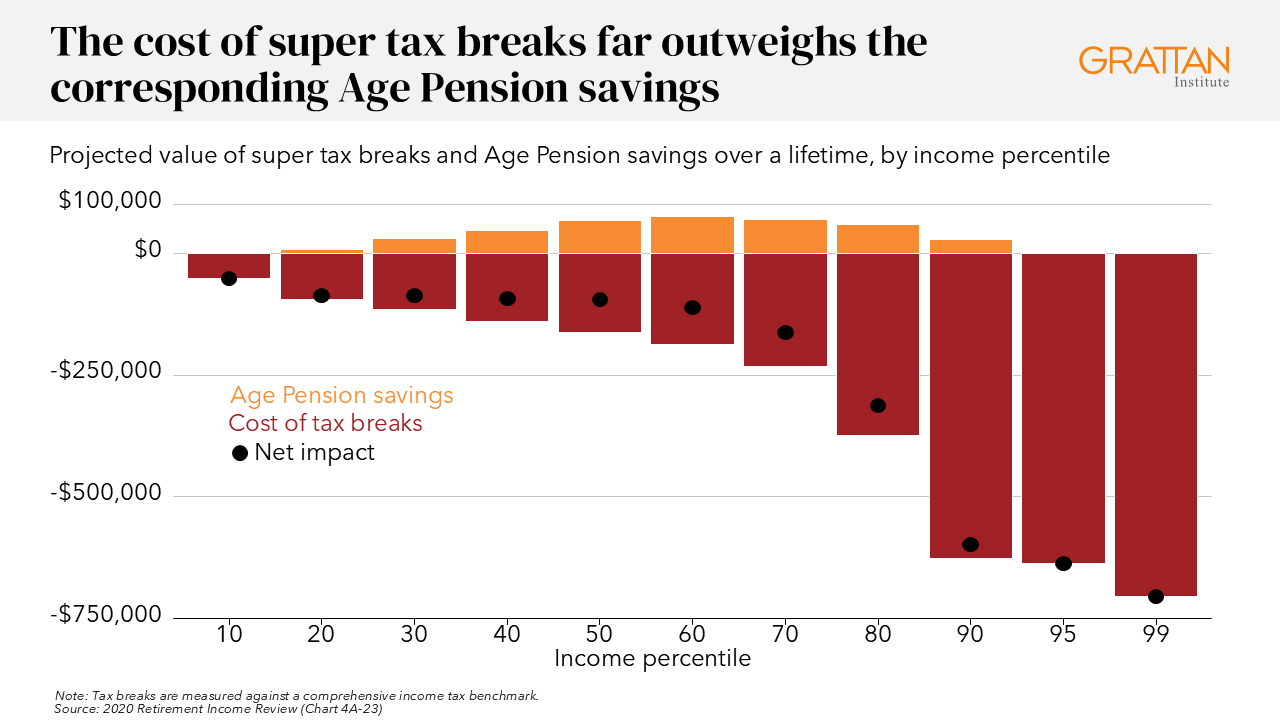

Nor do super tax breaks materially reduce Age Pension spending. Instead, the cost of super tax breaks far outweighing the Age Pension savings they produce. That’s because the bulk of the benefits going to higher-income earners who would never receive the Age Pension.

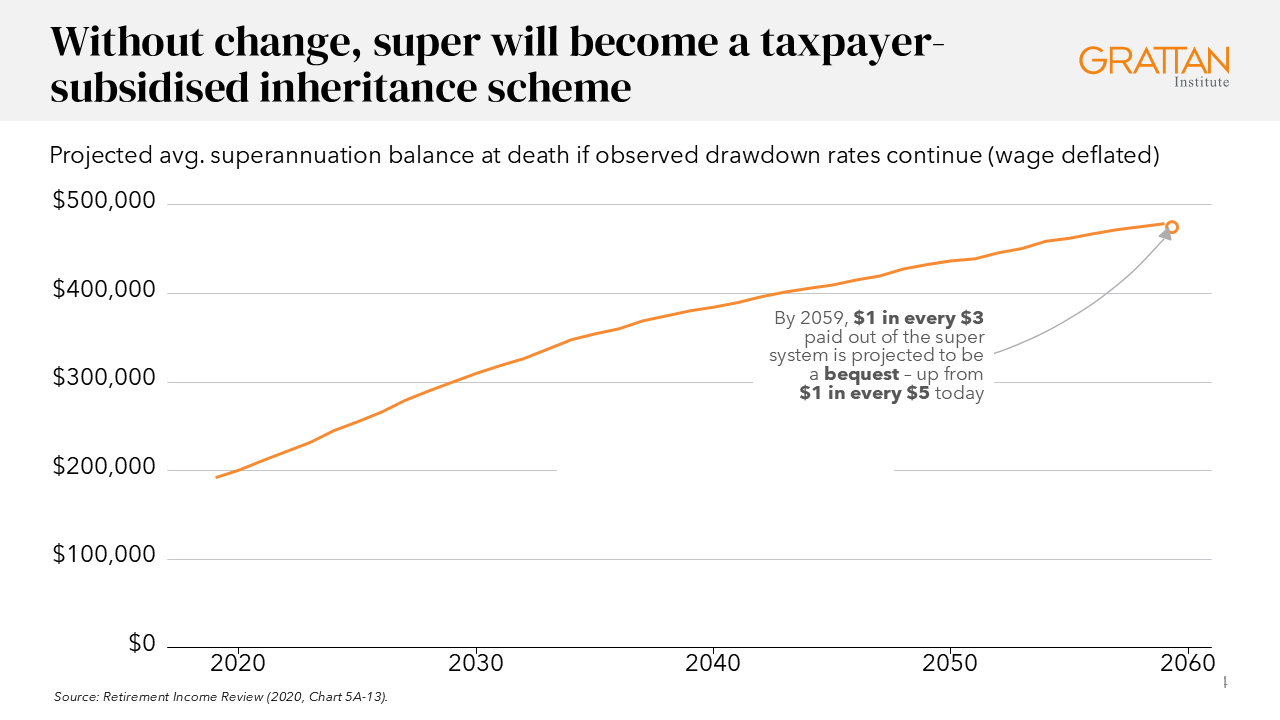

Further, much of what is saved for retirement never actually gets spent.

Few retirees draw down on their retirement savings, and many are net savers. Treasury projects that by 2060, one in every three dollars paid out of the super system will be a bequest, up from one in every five dollars today.

This is turning Australia’s $4+ trillion-dollar compulsory superannuation system into a massive taxpayer-subsidised inheritance scheme.

Super tax breaks should be offered only where they support a policy aim

So, everyone – or almost everyone – agrees that super tax breaks need to be reformed.

But what principles should guide our efforts?

It’s helpful to start by asking why we offer super tax breaks in the first place. That’s because these tax breaks should be offered only where they support a policy aim.

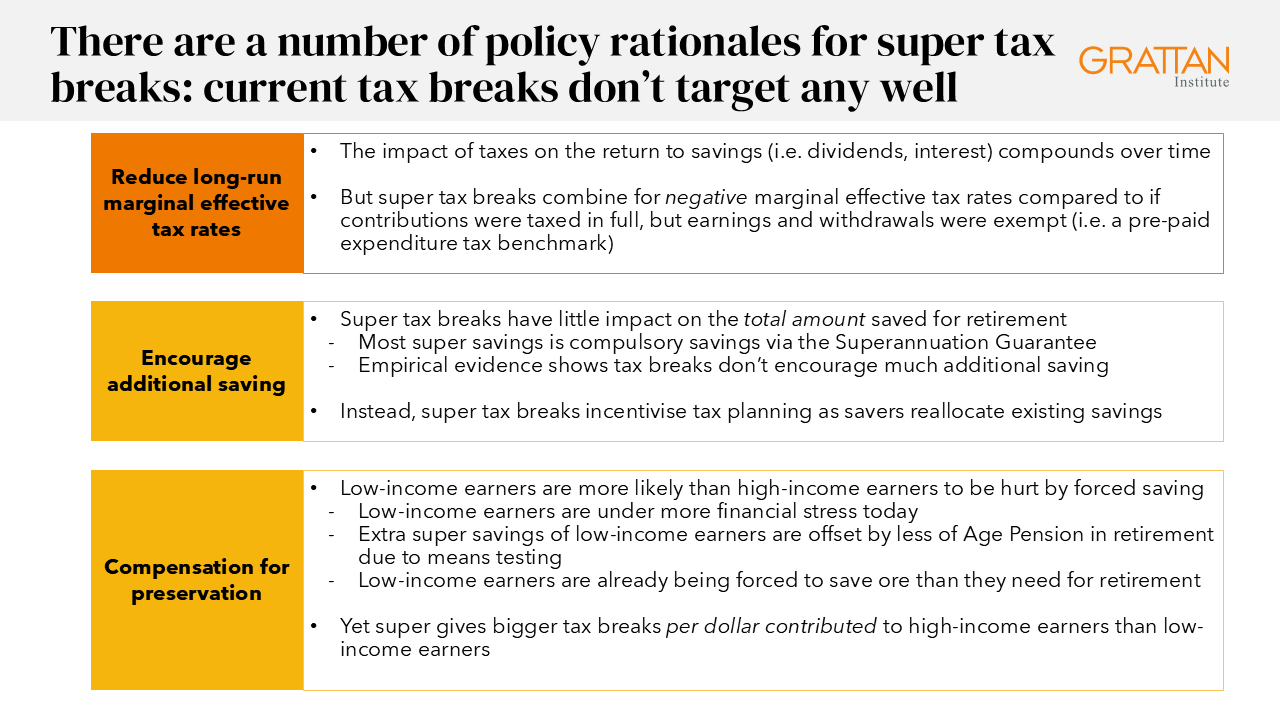

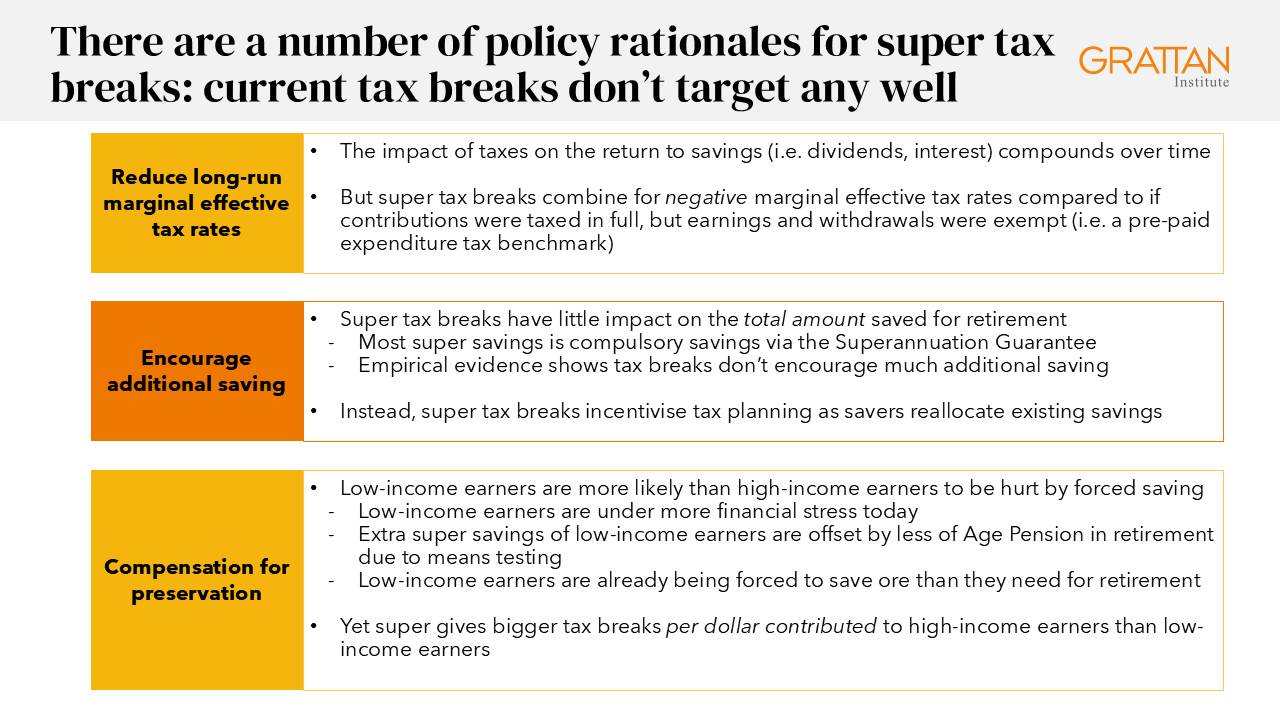

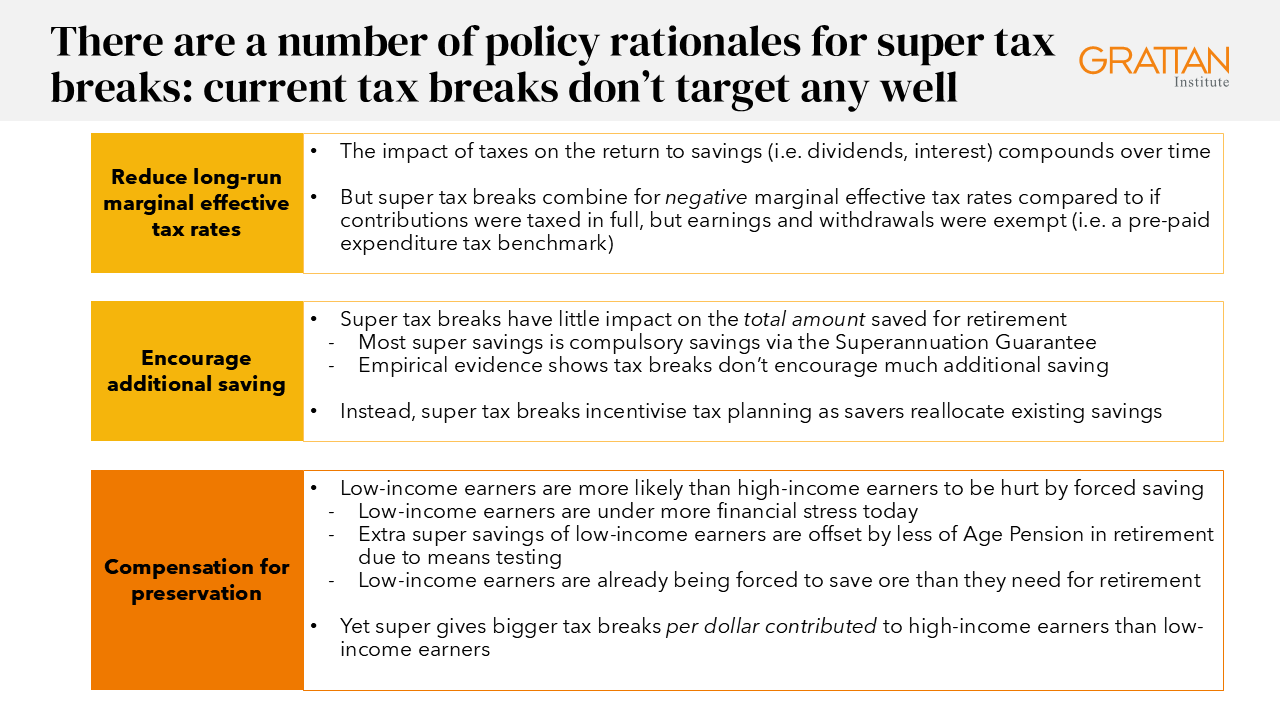

Three rationales are typically put forward.

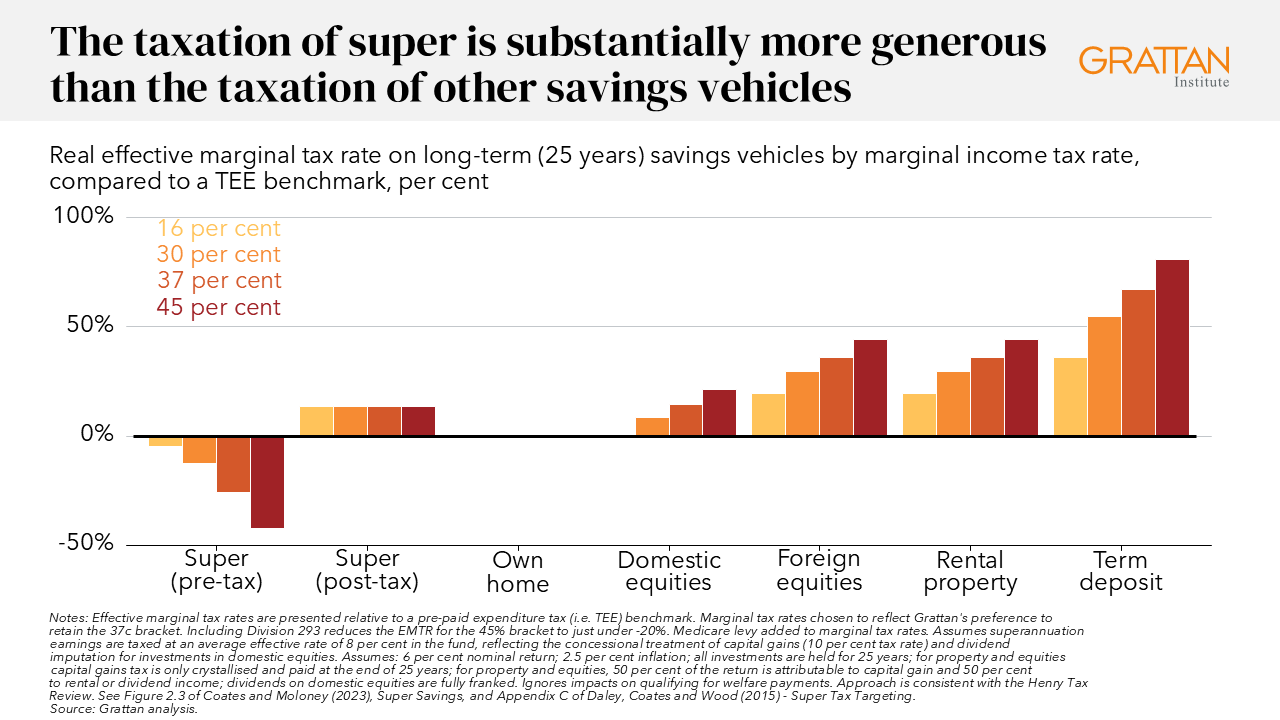

First, it’s generally agreed that tax rates on the return from savings, especially long-term savings such as super, should be lower than taxes on income from working. The impact of taxes on savings compounds over time, so the impact on future consumption can be much larger than the headline rate of tax, the longer savings are held. It’s like compound interest, but in reverse.

Some go further and argue for an “expenditure tax treatment” for savings, where the return from saving (i.e. the dividends, interest, or capital gains) is totally exempt from tax.3For example, see: Carling, R. (2015) Right or Rort? Dissecting Australia’s Tax Concessions, Research Report, April 2015, Centre for Independent Studies.

But tax breaks on super contributions and earnings combine for a negative marginal effective tax rate for most income earners, compared to an expenditure tax benchmark where tax was paid on income when earned, and then both earnings and withdrawals were tax-free.4Treasury estimates showed that Australia’s super tax breaks cost $11 billion more in forgone tax revenue in 2013 (and would cost more today) than if Australia taxed super contributions at full marginal rates of personal income tax but exempted earnings and withdrawals from tax. See: Treasury (2015), Tax Expenditures Statement 2014.

There is no justification for taxing super more generously than an expenditure tax benchmark, and good reasons to accept a much less generous tax treatment of super savings.5The optimal tax treatment of savings remains contested. The UK’s Mirrlees tax review concluded that to avoid bias against savings, only the risk-free component of investment returns need be tax free. However, even that is contested. Recent analyses have concluded that even the risk-free return on savings should be taxed, albeit at a lower rate than other income. Banks and Diamond (2010). Breunig et al (2020, p. 52) recommended a universal tax rate of between 5 per cent and 20 per cent on all savings.

So, super savings should be taxed more, but still at a lower rate than wages.

Second, and relatedly, many argue that super tax breaks are supposed to encourage additional savings, over and above compulsory contributions.

Yet the evidence suggests tax breaks for retirement savings have little impact on the total amount saved.

As the 2020 Retirement Income Review concluded, “tax concessions appear to have a weak influence on overall savings behaviour”.6Callaghan, M., Ralston, D., and Kay, C. (2020), Retirement Income Review, p.58.

Instead, it’s compulsory super that lifts national saving, and reduces pressure on the Age Pension.

But people with higher incomes, and older savers, tend to switch their savings into whichever investment vehicle pays the least tax.7For a more detailed discussion, see: Daley, J., Coates, B. and Wood, D. (2015), Super Tax Targeting, p.21; and Callaghan, M., Ralston, D., and Kay, C. (2020), Retirement Income Review, p.420-423.

The implication is that we should move to harmonise the tax treatment of savings at the same rate, as others have proposed. Therefore, making super tax breaks less generous is a necessary first step towards broader reforms to taxing savings.

Third, super tax breaks also arguably compensate people for being compelled to lock up their savings in super until retirement.

But low-income earners are more likely than higher-income earners to be hurt by forced saving via super. They are under more financial stress while working, and live shorter lives on average, so have less time in retirement to spend their super.

Therefore, the tax break offered on each dollar of super savings should be higher for lower-income earners than high-income earners. Unfortunately, Australia’s current system does the opposite.

Contributions tax breaks are not well targeted at these policy goals

Tax breaks on superannuation contributions cost the budget $30 billion a year.8Treasury (2025), Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement, Table 2.1. Estimate is adjusted down reflecting the ratio between the ‘revenue gain’ and ‘revenue foregone’ estimates for super earnings tax breaks last published in Treasury (2022), 2021 Tax Benchmarks and Variations Statement, to generate an updated ‘revenue gain’ estimate 2025-26.

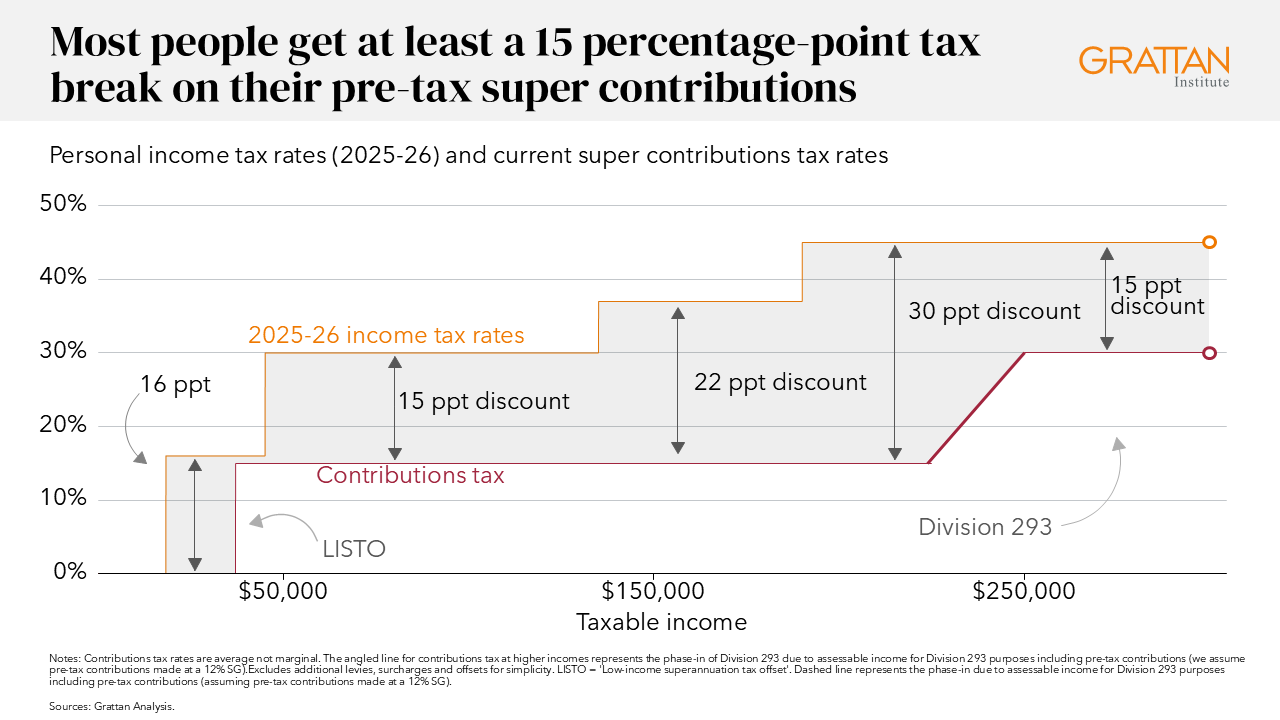

These tax breaks arise because most super contributions – about three quarters – are made from pre-tax income, with most taxed at a flat rate of just 15 per cent.

Tax breaks on contributions are skewed to high-income earners because they contribute more dollars. But this skew is exacerbated because high-income earners receive a larger tax break per dollar contributed to superannuation.

Contributions tax breaks should be better targeted by lowering the value of the tax break offered to high-income earners for each dollar they contribute to super.

Grattan Institute’ 2023 report, Super Savings, proposed doing just that using the existing tools in the system.

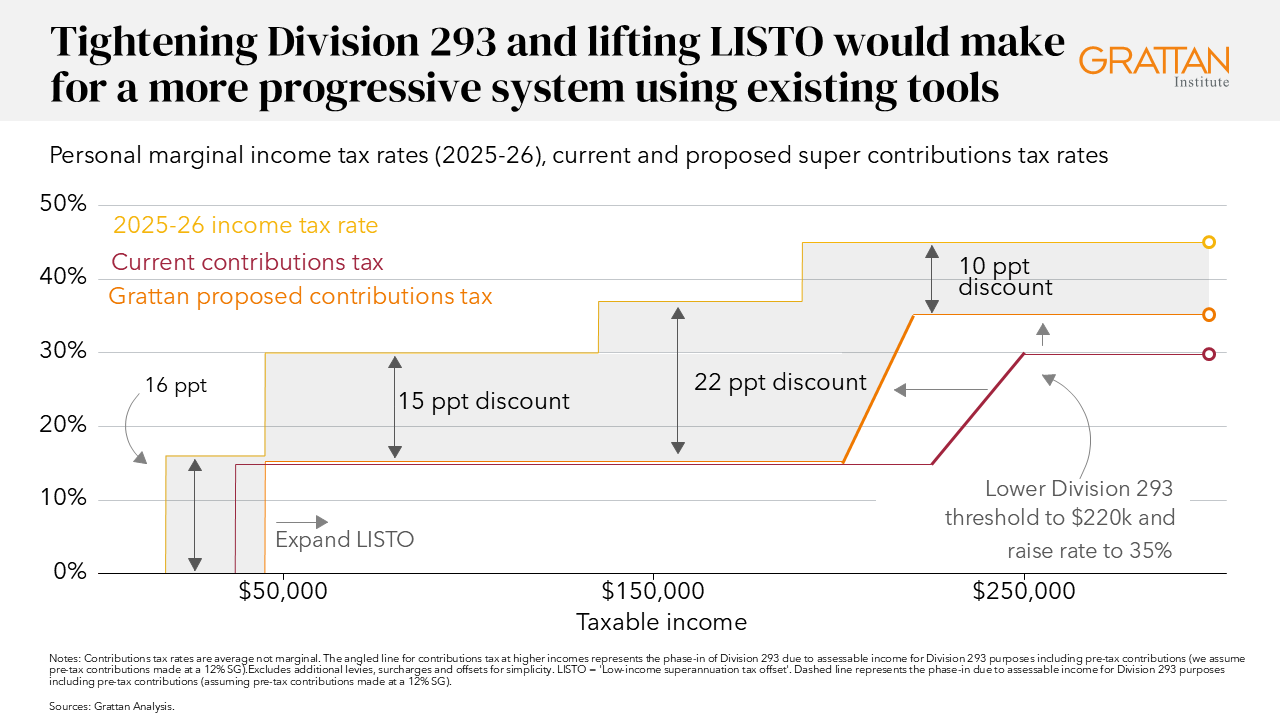

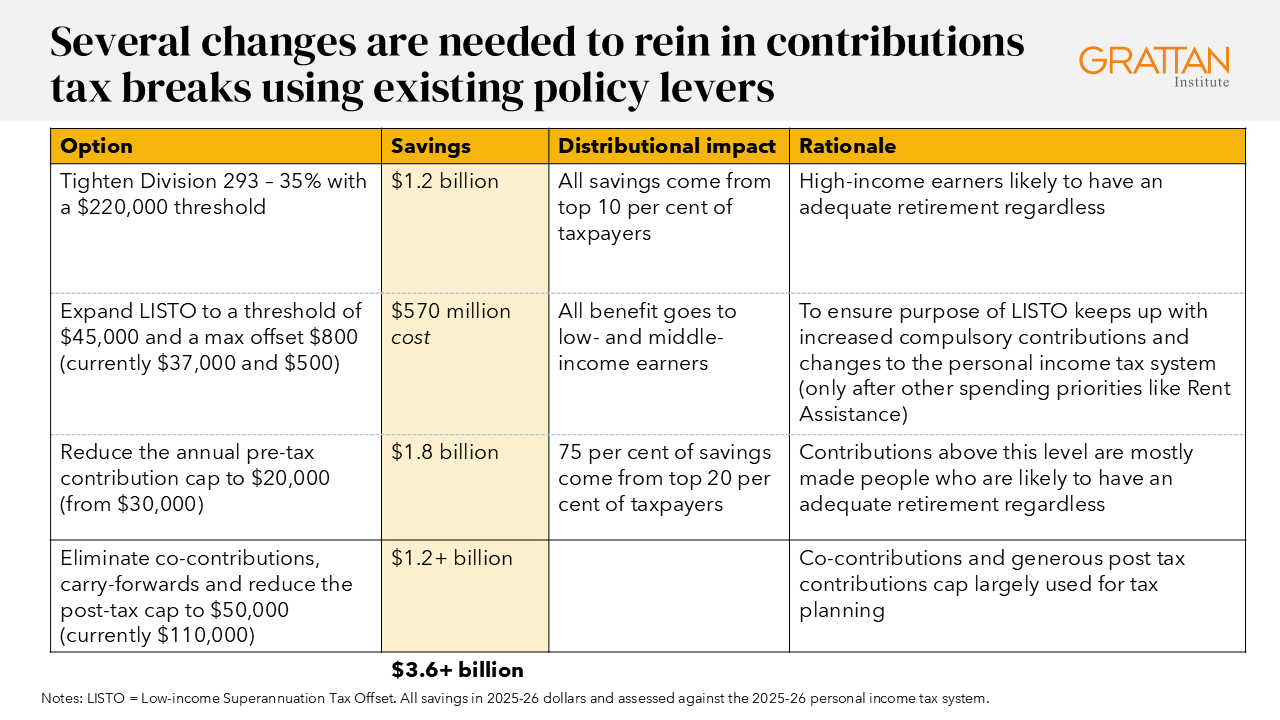

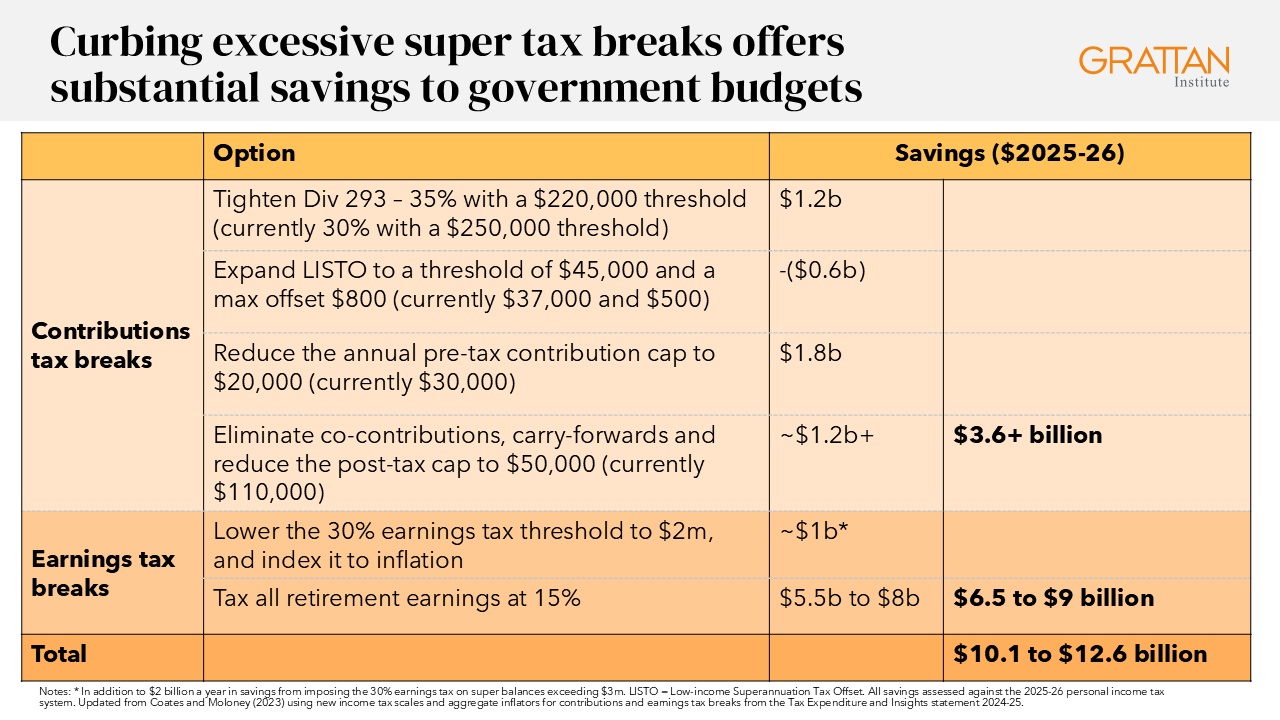

We recommended that the pre-tax contributions of people earning more than $220,000 a year should be taxed at 35 per cent, instead of the 30 per cent rate charged to those earning more than $250,000 currently, saving the budget $1.2 billion a year.

The government should also increase the Low-Income Superannuation Tax Offset (LISTO) to $800 (from $500) and raise the threshold to which it applies to $45,000 a year (from $37,000), costing $570 million a year.

These changes would mean lower-income earners receive at least a 15 per cent tax break on their contributions, vis-a-vis their marginal tax rate, compared to just 10 per cent for people earning more than $220,000 a year.

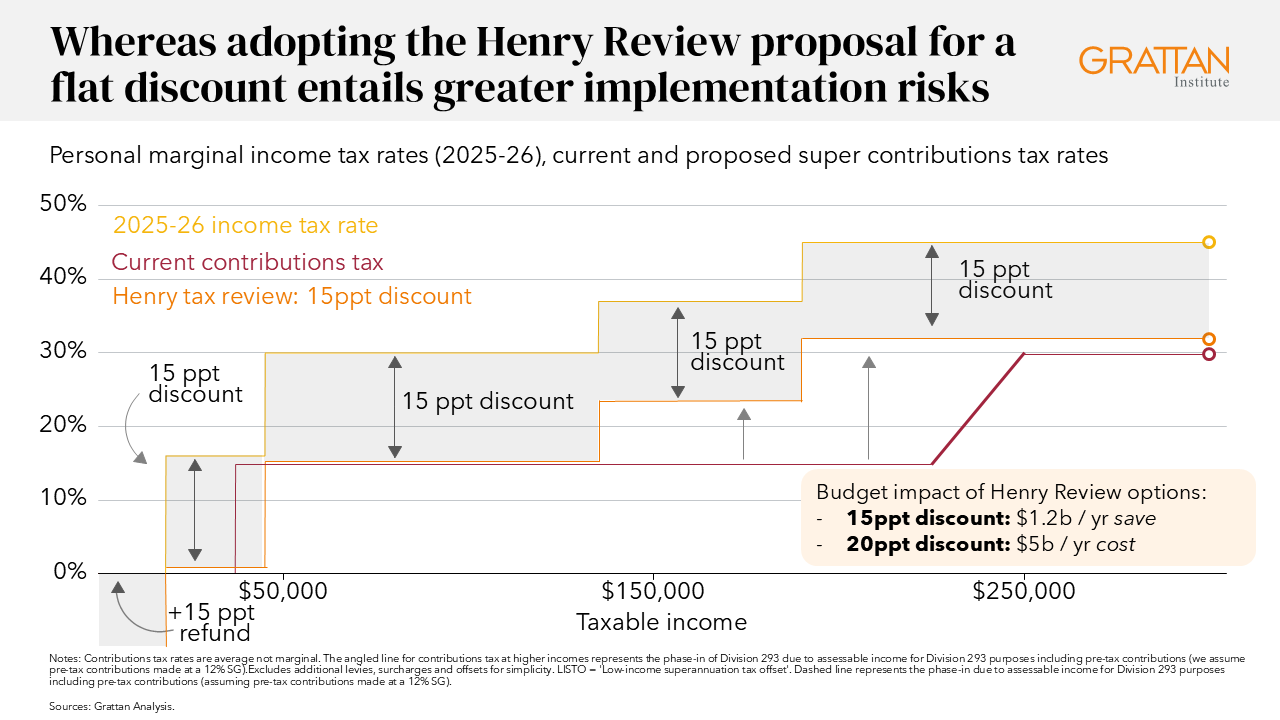

An alternative, put forward in the 2010 Henry Tax Review would be to tax pre-tax contributions at an individual’s marginal tax rate, less a flat-rate refundable offset. Henry proposed that the value of this offset be set to ensure most taxpayers would pay an effective 15 per cent contributions tax rate.

At the time of the Henry Review, it was foreseen that this offset would be a 20 per cent discount to marginal rates of personal income tax, but we estimate such a reform today would cost the budget an extra $5 billion a year.

Whereas a 15 per cent discount to marginal rates would save the budget roughly $1.2 billion a year.

But there’s a catch. The Henry Review model requires greater administrative upheaval – with contributions made from post-tax income and a flat rebate applied — adding both uncertainty and administrative cost to the super tax reform project.

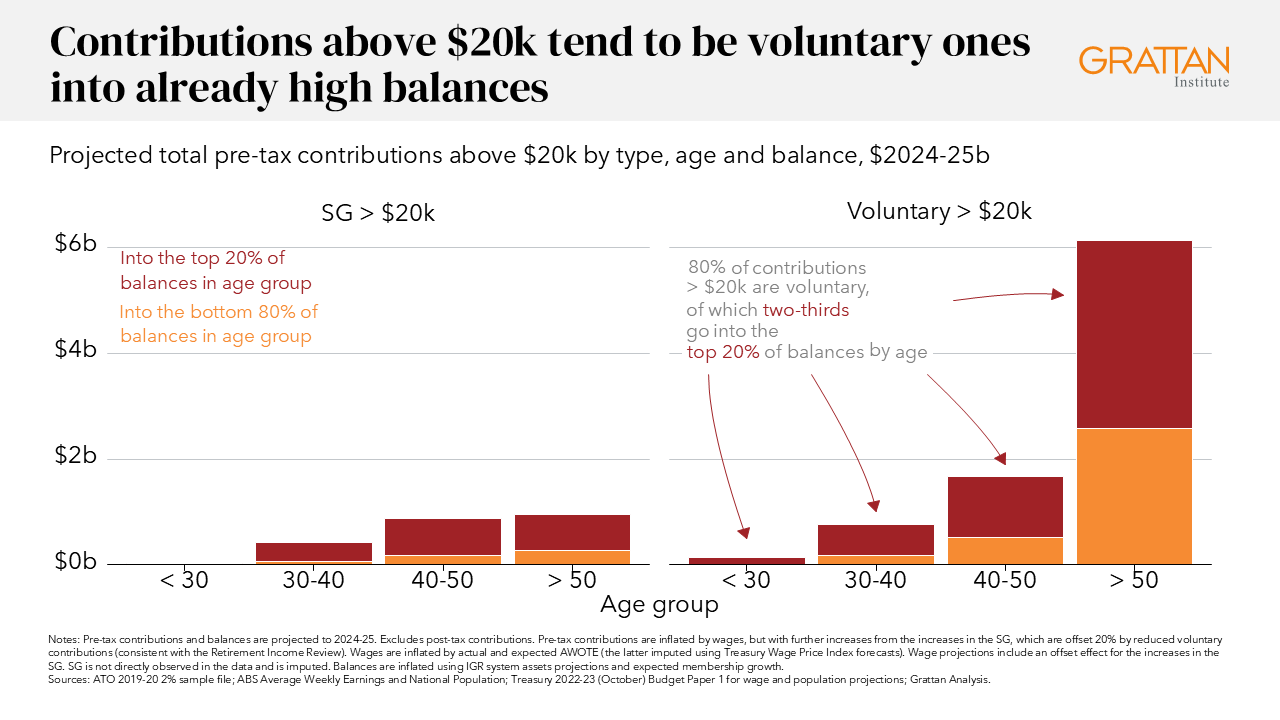

In addition to the value of the concession per dollar of contributions, a lot of those large pre-tax super contributions look like tax minimisation by wealthier, older Australians, rather than genuine retirement saving. So, the cap on pre-tax super contributions should be lowered, from $30,000 to $20,000 a year, saving $1.8 billion a year.

A $20,000 cap on pre-tax contributions would allow someone earning about $167,000 a year – more than twice median full-time earnings – to get tax breaks on all their compulsory contributions.

Even if they make no voluntary contributions, they would retire with a super balance of about $1.35 million in today’s dollars and be ineligible for any Age Pension.

Finally, eliminating co-contributions and carry-forward provisions – both of which are intended to encourage catch-up contributions but instead largely facilitate tax minimisation – would save at least a further $1.2 billion a year. Together these reforms to contributions tax breaks would save nearly $4 billion a year, and do so almost exclusively by reducing the concessions available to the top 20 per cent of Australians by incomes.

Earnings tax breaks

Earnings tax breaks arise because earnings on superannuation balances are taxed less than earnings on most savings held outside super.

These tax breaks at present cost the budget $26 billion a year9Treasury (2025), Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement, Table 2.2. Estimate is adjusted down reflecting the ratio between the ‘revenue gain’ and ‘revenue foregone’ estimates for super earnings tax breaks last published in Treasury (2022), 2021 Tax Benchmarks and Variations Statement, to generate an updated ‘revenue gain’ estimate 2025-26., and their costs are expected to rise sharply in coming decades as the super system matures.

Tax-free super earnings in retirement in particular mean more of the burden of funding public services falls on younger taxpayers.

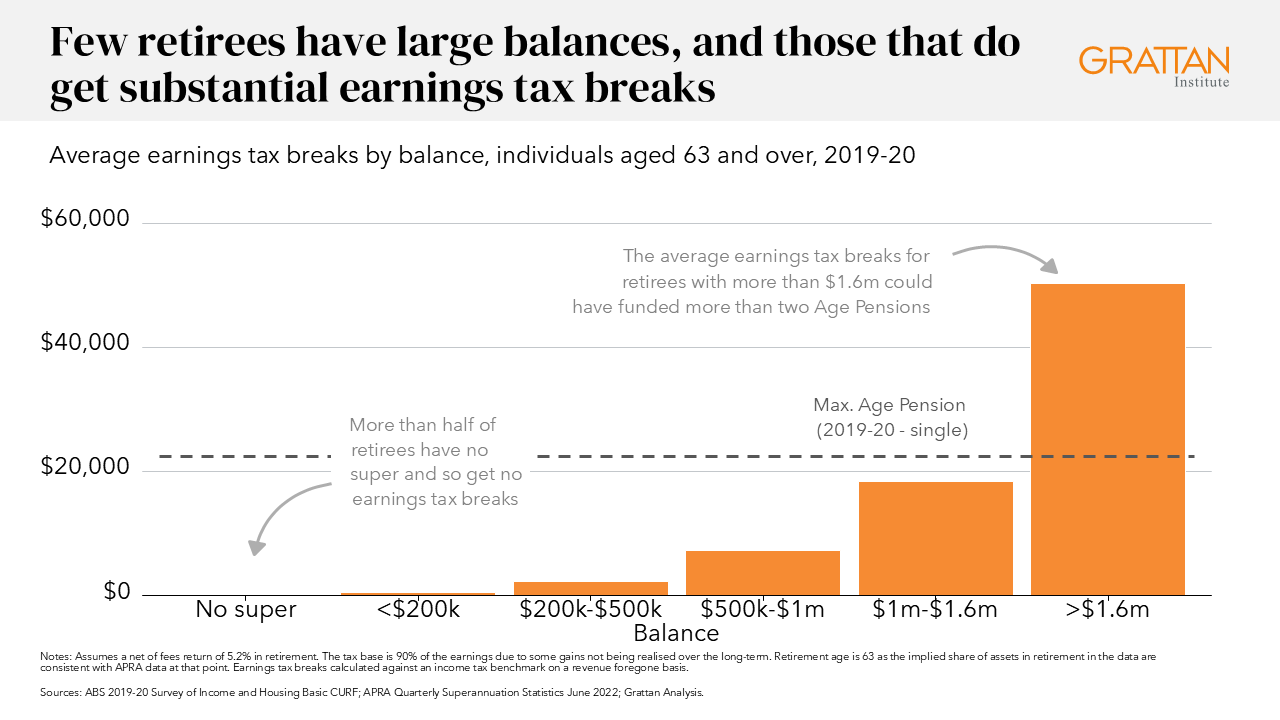

And the annual value of these concessions for someone with more than $1.6 million in super in retirement can easily exceed twice the maximum annual value of the Age Pension.

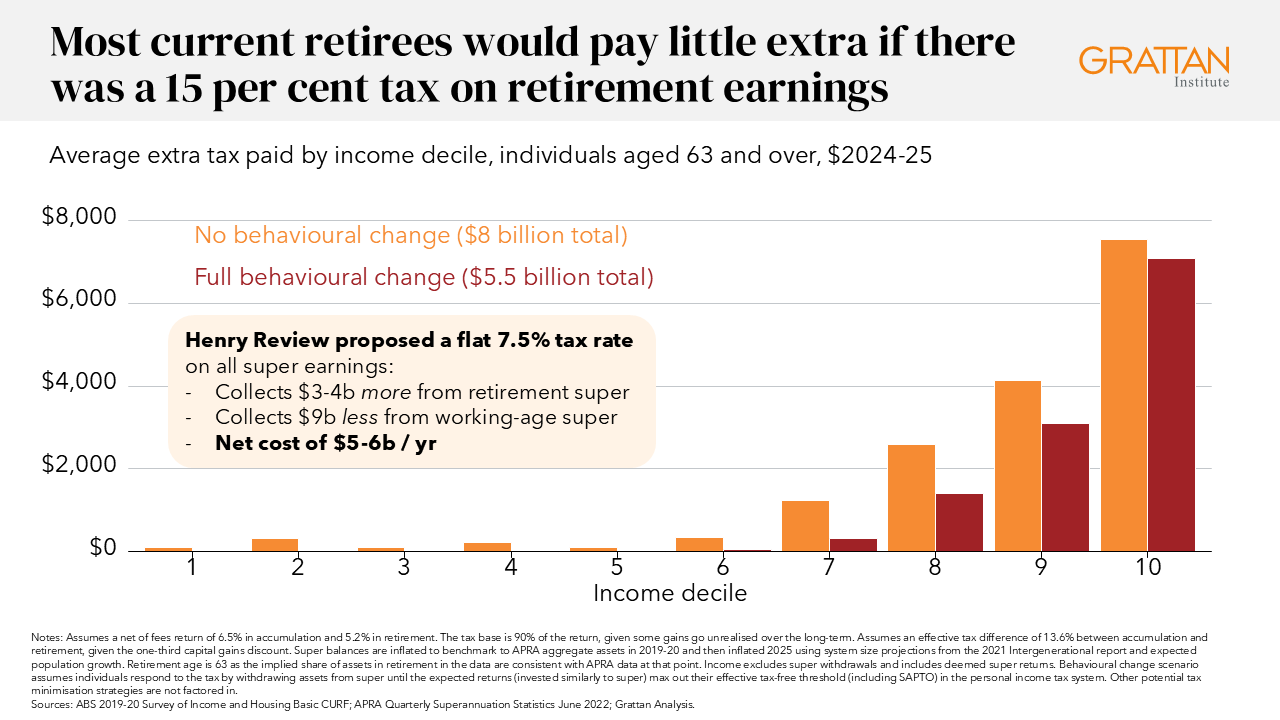

Super earnings in retirement should be taxed at 15 per cent, the same as super earnings before retirement. This would save the budget at least $5.5 billion a year, and much more in future, while also making super simpler.

More than 70 per cent of this revenue would come from the top 20 per cent of retirees. The top 10 per cent would pay an extra $7,000 to $7,500 a year on average, whereas the poorest half would no more than $200 more each on average.

In contrast, taxing all super earnings at 7.5 per cent at the Henry Tax Review proposed is far too generous, costing the budget a further $5-to-6 billion a year.

It would do so by collecting $3-4 billion a year more from the earnings on retirement-phase super, but also by collecting $9 billion a year less from working-age super earnings.

That is, it would make super earnings tax breaks even more expensive and unsustainable than they already are.

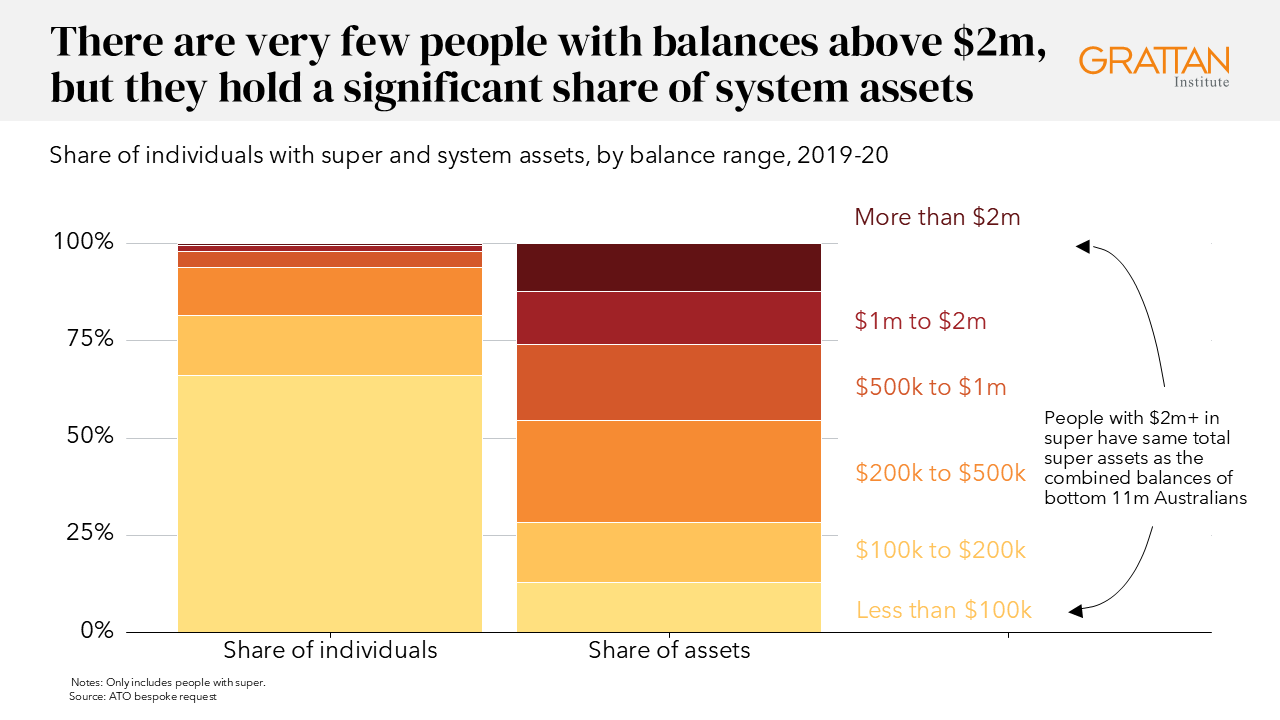

A final issue is that a significant share of superannuation is now held in accounts with very large balances that are unlikely to be spent down in retirement.

For instance, balances of more than $2 million make up a tiny fraction of all accounts, but hold nearly as much money as the two-thirds of Australians with less than $100,000 in super.

And we’ve all seen media reports that the largest single super accounts in Australia hold up to $500 million,10Rashida Yosufzai, “An Australian has over $500 million in super. How is that even possible?”, SBS News which would entitle them to super tax breaks worth $10 million a year, or the equivalent of more than 300 Age Pensions.11Grattan Institute analysis. Assumes rate of return of 6 per cent on super assets.

I’m not going to re-prosecute the arguments for this charge,12See Coates and Moloney (2025), “Actually, Gen Z stand to be the biggest winners from the new $3 million super tax”, The Conversation, 26 May 2025. or respond to critiques of that proposal, other than to say that the proposed change is responding to a real problem, albeit with an imperfect policy design.

A better reform would be to apply the new tax to super accounts larger than $2 million – rather than $3 million as proposed by the government. And then – and only then – should the threshold be indexed.

A package of reforms

In total, Grattan Institute has identified reforms to super tax breaks that would trim the cost of these concessions by upwards of $10 billion a year.

Under our proposed reforms, super would remain highly concessionally taxed, costing the budget more than $40 billion a year.

But those tax breaks that remain would genuinely support Australians’ retirement incomes, not tax minimisation and estate planning.

That includes a package of reforms to contributions tax breaks that would save nearly $4 billion a year, which would appear do so almost exclusively by reducing the concessions available to the top 20 per cent of Australians by incomes.

And it includes taxing super earnings in retirement at 15 per cent – the same rate that applies to working age super today. That’s a harder reform, because it affects many more older Australians across all incomes, even if only very modestly. But tax reform will inevitably require some tough choices. And the inescapable fact is that super tax breaks need to be wound back as part of any serious tax reform package