Low job mobility is holding Australia back

by Trent Wiltshire

The federal government is searching for ways to lift Australia’s sluggish productivity growth, and one key lever is making better use of people’s skills and talents.

When workers can more easily move into jobs where they are most suited and productive, there is a large economic payoff: Higher wages and productivity, and a more dynamic and prosperous Australia.

But low job mobility – mostly driven by structural problems in the economy – is holding Australia back.

Job mobility has declined

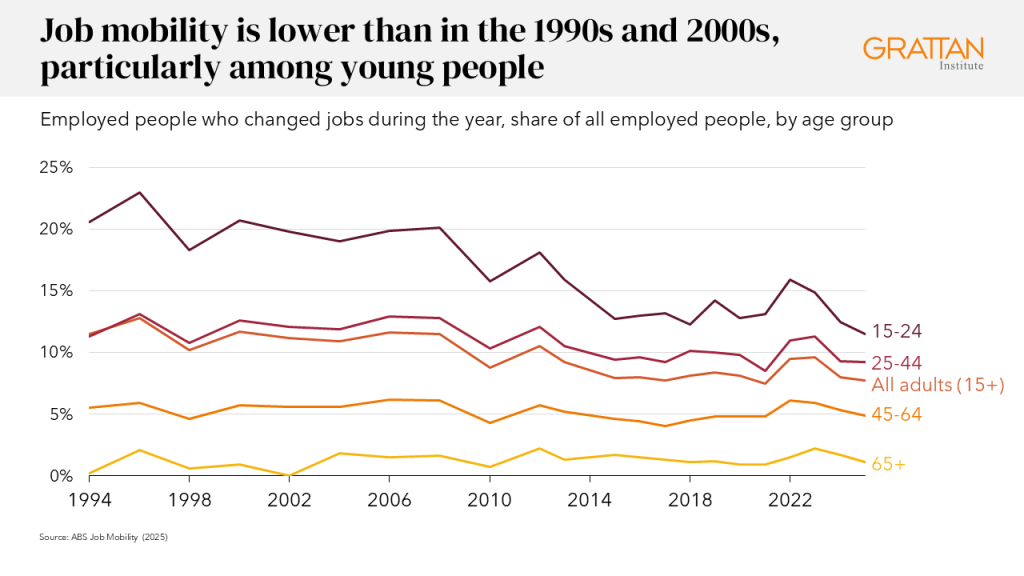

The proportion of workers in Australia who change jobs each year has fallen since the 1990s (see chart below).

In the year ending February 2025, 7.7 per cent of employed adults changed jobs. This proportion has been broadly steady over the past decade, except for a temporary rise post-pandemic due to a catch up in job changes and a strong labour market. But it is well below the 10-13 per cent who changed jobs each year in the 1990s.

Lower job mobility is especially evident among young workers. But the decline in job mobility is also partly due to the ageing of the workforce – older workers tend to change jobs and locations less often.

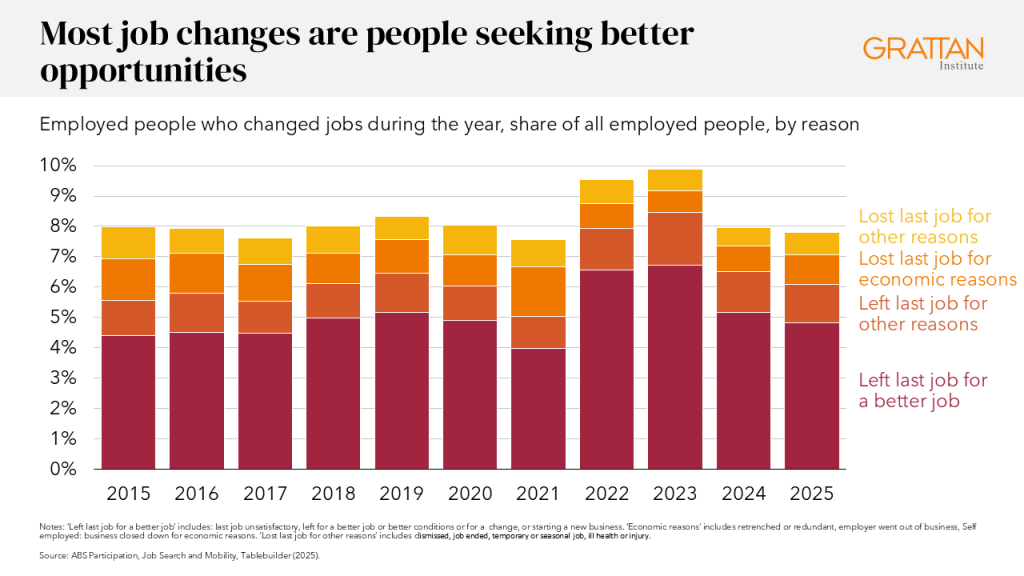

As the below chart shows, most job changes are people moving to a better job for them. In recent years, about two-thirds of people who changed jobs did so for a better job (including because they were looking for a change or to start a business).

Only about 10-20 per cent of job changes were due to people losing their job for economic reasons, such as redundancy, a lack of work, or because their employer went out of business.

When people move jobs, it’s typically a drastic change. The Productivity Commission found that about 70 per cent of occupation transitions and 80 per cent of industry transitions were big changes, such as from manufacturing to professional services.

Lower productivity growth

Subdued job mobility has been a factor in Australia’s weak productivity growth since the mid-2010s.

Higher job mobility means more people in higher-paying, more-satisfying jobs. It also means higher productivity growth, as more workers move into more productive jobs and more productive firms.

Job mobility also boosts productivity by contributing to knowledge spillovers.

Other forces also weigh on better allocation of talent. Notably, persistent gender segregation in Australia’s workforce limits people’s choices, often channelling women disproportionately into lower-paid caring roles and men into technical and trade jobs.

How to boost job mobility

Governments can support job switching and boost productivity by addressing some of the underlying problems in the economy that are impeding job mobility.

High housing costs, particularly in our major cities, is one factor.

High property prices mean higher stamp duty, which discourages people from moving to better jobs (although recently it has meant more people renting, which may have supported mobility because renters are more mobile).

Improving housing affordability by encouraging more home-building would enable more people to move and live closer to jobs that better suited them.

The decline in competition and business dynamism in Australia is also contributing to lower job mobility. Fewer new start-ups mean fewer opportunities for workers. And if weak competition means lower-productivity firms are less likely to go out of business, then there is less movement of workers to higher-productivity, growing firms.

The low rate of JobSeeker is a barrier to some people finding a job, as the it means people may not have the resources to effectively search for a suitable job.

Our weak safety net may also be a deterrent to moving jobs. For example, a worker could be discouraged from moving to a new, high-paying job with a start-up due to the risk they will potentially lose their job if the business fails, and they end up on JobSeeker struggling to make ends meet.

As the Grattan Institute has previously argued, the federal government should increase JobSeeker by at least $60 a week and index the payment to grow in wages, to keep pace with community living standards.

The federal, state, and territory governments should also lower regulatory barriers that make it harder for workers to move to a better job.

First, governments can support mobility by reforming occupational licensing.

The federal government should work with state and territory governments to streamline occupational licensing by expanding automatic mutual recognition, creating a national licensing regime for specific occupations (particularly in construction trades), expanding international mutual recognition schemes, and abolishing occupational licenses where the costs exceed the benefits.

The Productivity Commission estimates that removing unnecessary occupational licensing requirements would increase productivity and boost GDP by up to 0.4 per cent.

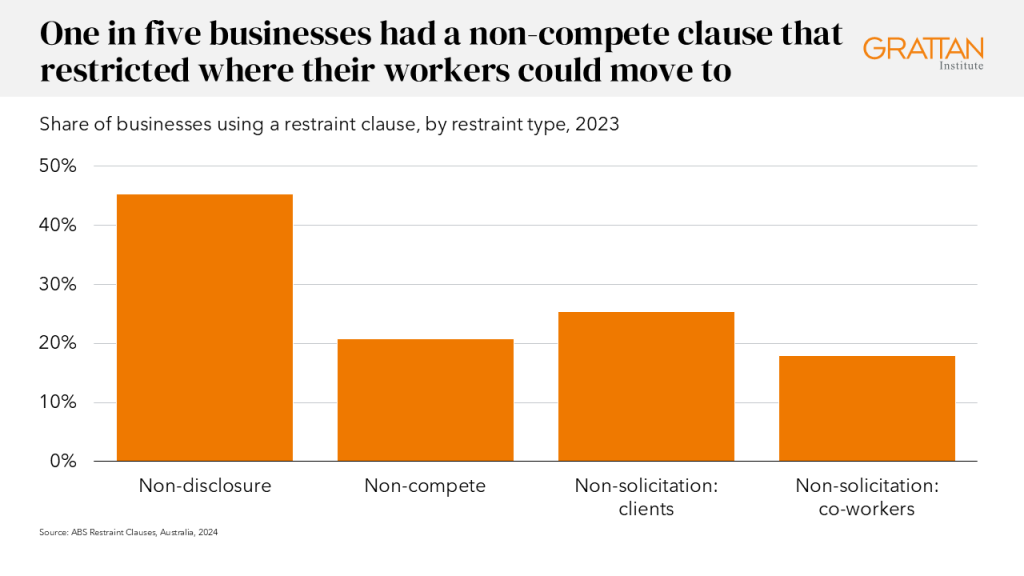

Second, the federal government should proceed with its proposal to ban non-compete clauses for workers earning less than the high-income threshold defined in the Fair Work Act (currently $183,100).

Non-compete clauses limit mobility and hold back productivity gains, and are used by about 20 per cent of businesses (see chart below).

The federal government also plans to amend the Competition and Consumer Act to stop anti-competitive practices among businesses, such as ‘no poach’ agreements that stop workers from being hired by competitors.

The government’s proposals seem a reasonable compromise between protecting business interests and allowing workers greater freedom to find a new job.

The Albanese government has put boosting productivity growth at the top of its second-term agenda. Removing barriers that stop workers moving to the most suitable jobs is a great place to start to make Australia more prosperous.