Published at The Conversation, 19 April 2020

We knew it would be bad. But we’d hoped it wouldn’t be quite this bad.

Over the past few weeks, we at Grattan Institute have been working on ways to estimate the impact of the COVID-19 shutdown on jobs in Australia.

It’s a complex task, with few obvious precedents.

The results, detailed in our new working paper, Shutdown: estimating the COVID-19 employment shock, are worrying.

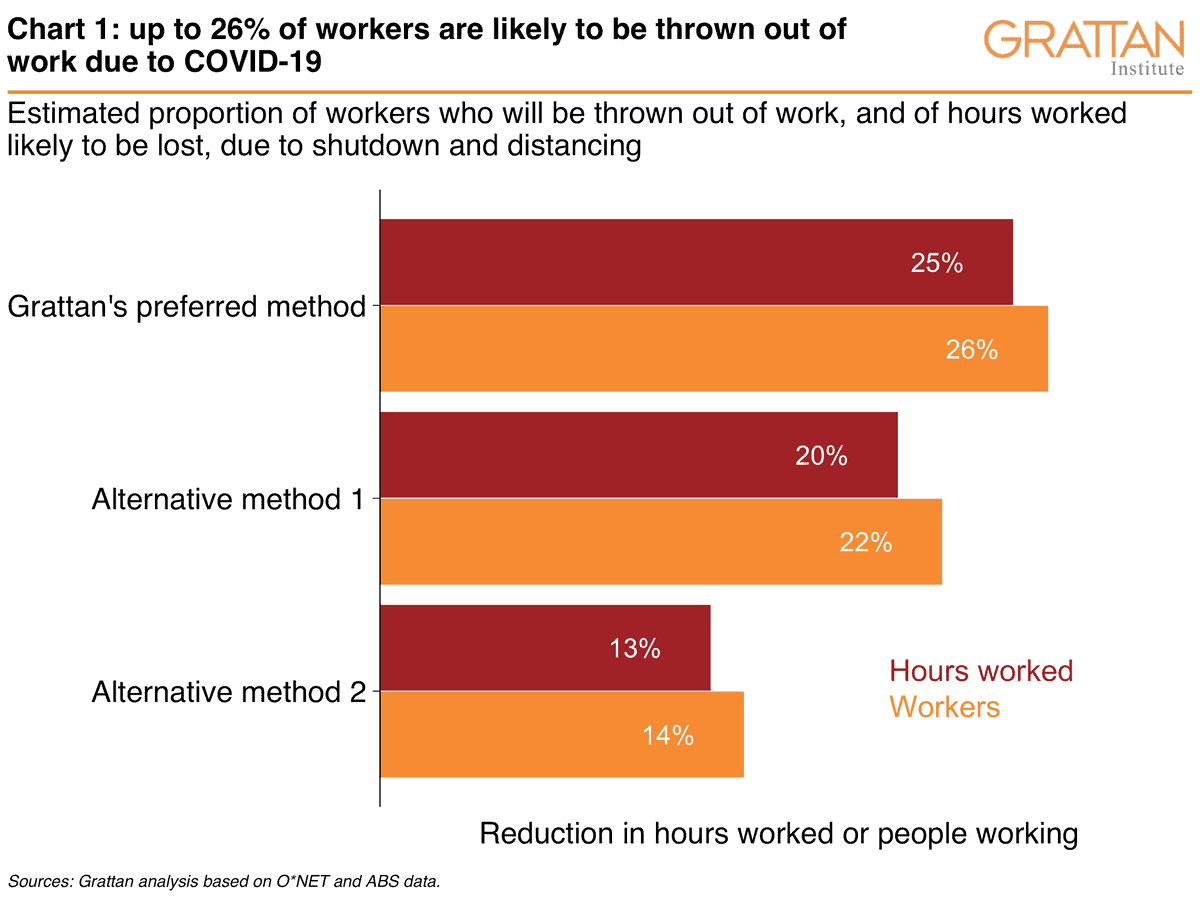

Our estimate is that between a sixth and a quarter of Australia’s workforce is likely to be out of work because of the COVID-19 shutdown and social distancing.

It derives from two sources of information.

The first is data from the United States on the extent to which each occupation requires workers to be near other people.

The “physical proximity” requirements of a job are generally likely to be a good guide to how likely it is the job can continue during the shutdown.

The second source of information is a set of estimates by Grattan researchers of the extent to which jobs are under threat in each of 88 industries in Australia.

Our preferred method for estimating the hit to jobs combines both these sources.

We also use two alternative methods, each of which relying on a single source of data, which are outlined in our working paper.

Our preferred method finds that about 26% of workers – 3.4 million Australians – could be thrown out of work as a direct result of the shutdown and social distancing.

The alternative methods produce figures that are lower, but still distressingly high.

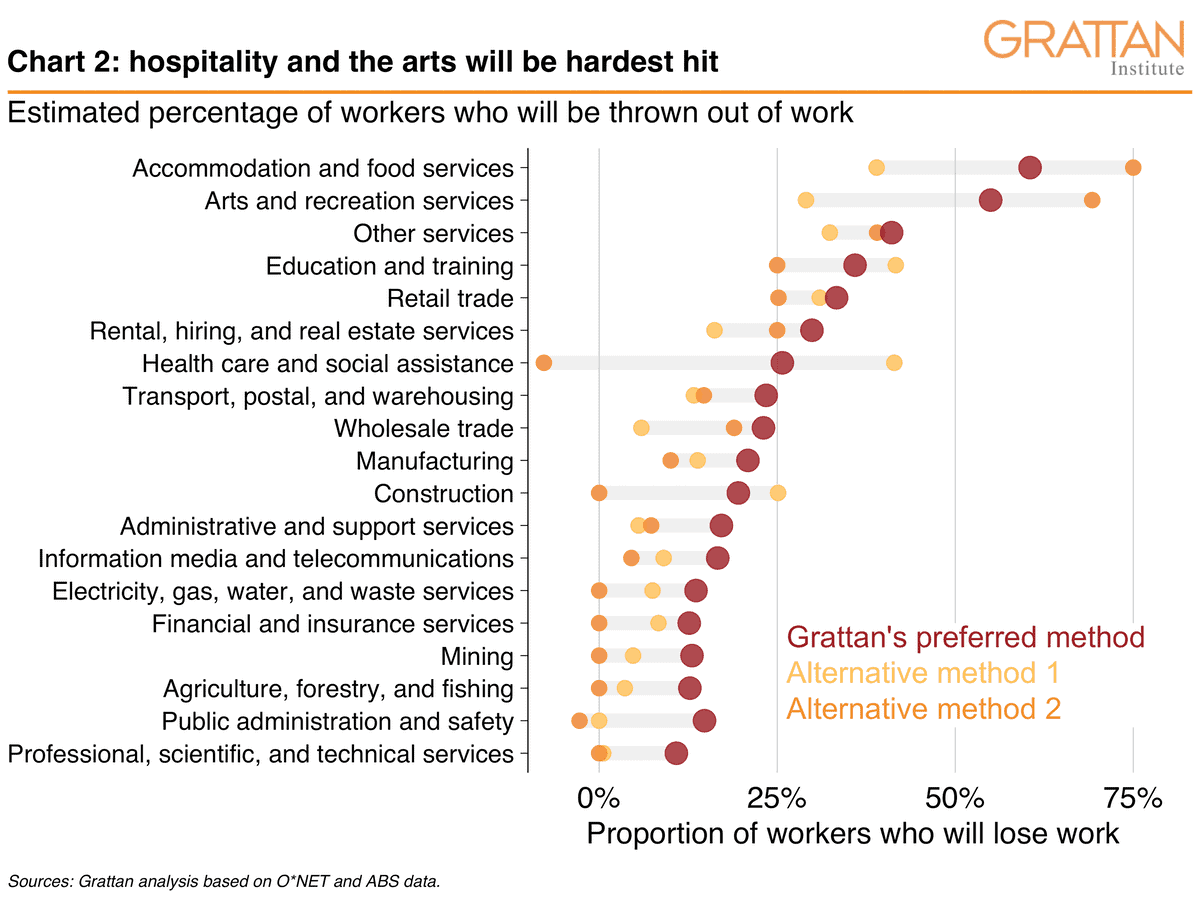

Unsurprisingly, we find the hospitality industry will be hardest hit. More than half of workers in the “accommodation and food services” industry are likely to be out of work as a result of this crisis.

The “arts and recreation services” industry is not far behind.

A range of professional industries – where people are more likely to be able to work from home – are much less likely to shed jobs in the weeks and months ahead.

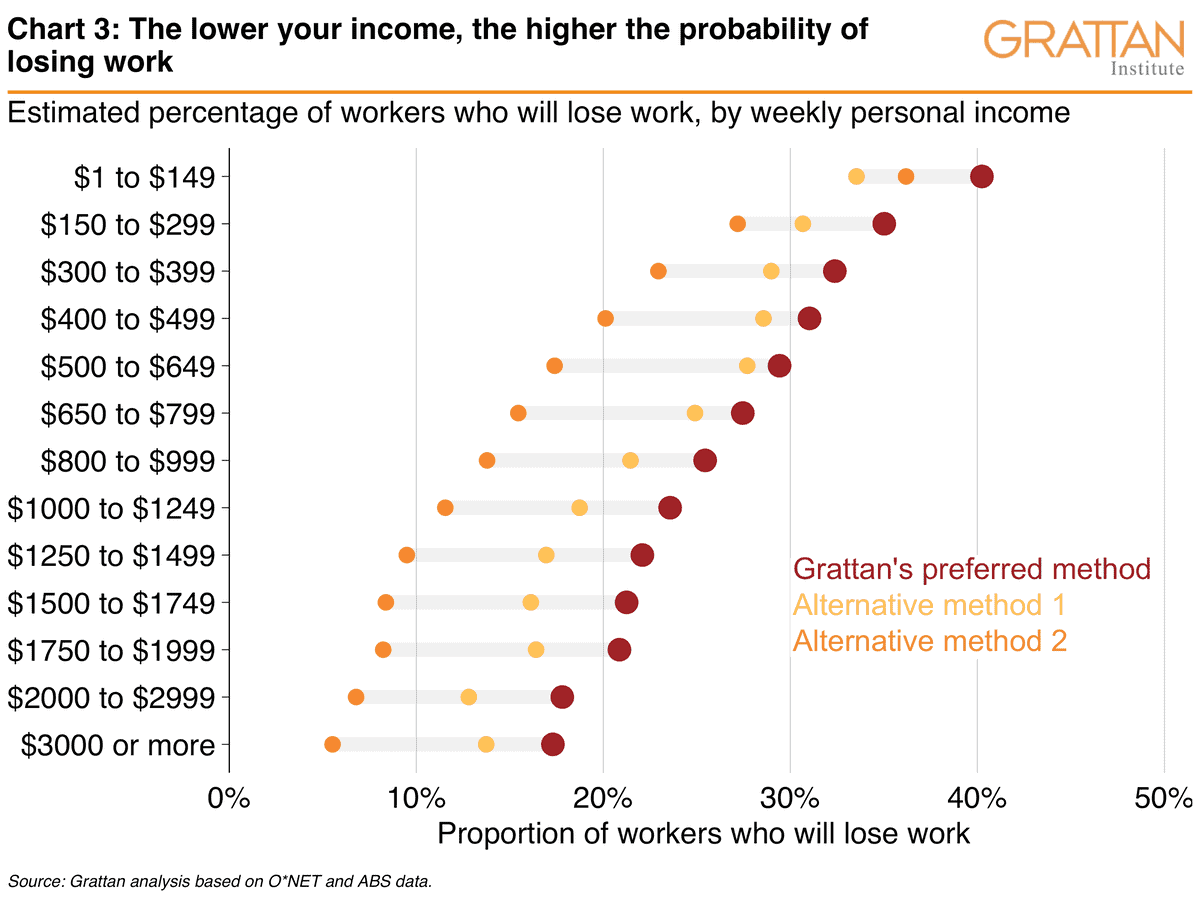

People on low incomes will be hardest hit, because the jobs in hospitality, retailing and the arts tend to pay less than the sort of professional jobs people can do from home.

Those in the lowest income are likely to be off work during this crisis. They are more than as likely to be without work as the highest-income workers.

As a general rule, the higher your income, the lower your chance of being affected by the crisis.

There is of course considerable uncertainty around our estimates of the job losses from COVID-19, especially by industry.

In some cases, the ‘preferred method’ yields results that are likely an over-estimate of the proportion of people who will lose work, such as in the finance and mining industries. In others, such as hospitality, the ‘preferred method’ figures may be too low.

Nonetheless our estimates strongly correlate with the share of firms which report that they have reduced worker hours in response to COVID-19.

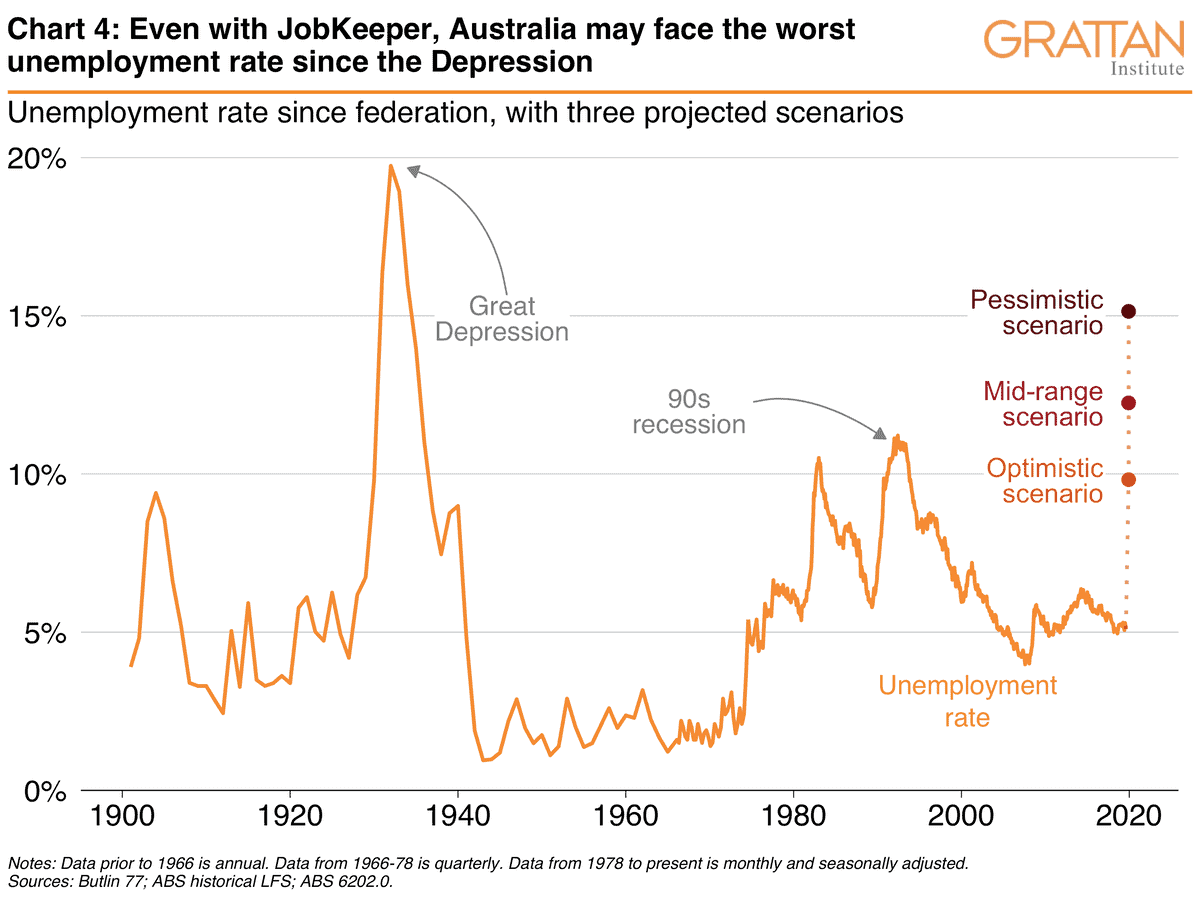

If all of those 3.4 million Australians moved from being “employed” to “unemployed”, the unemployment rate would spike to 30%.

But this extreme outcome won’t happen, because not everyone who loses work will cease being categorised as “employed”, and not everyone who ceases being “employed” will become “unemployed” – some will stop looking for work.

Some workers thrown out of work by the COVID-19 shutdown will still be classified by the Bureau of Statistics as “employed”.

Why? Because they may only be laid off for a short period. And because some people who lose work will continue to get paid thanks to the government’s A$130 billion JobKeeper program, and if you’re still being paid by your employer the Bureau of Statistics counts you as still “employed”.

Our expectation is that only about half of the people out of work will cease being “employed”. And of those who do completely lose their jobs – that is, stop being paid by their employer – about half will give up looking for jobs and not be counted as unemnployed, perhaps because they have “retired” or decided to concentrate on home duties.

If these assumptions are right, the unemployment rate will climb to about 12% in the June quarter encompassing April, May and June – the highest rate since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Under a more optimistic scenario in which more people continue being paid by their employers, the rate will still climb to about 10%, in line with treasury forecasts.

Under a more pessimistic scenario, the unemployment rate will leap to 15%.

Whichever assumptions are made, whatever methods are used, it is clear Australia now confronts one of the worst employment shocks in its history.

![]()