Published at The Conversation, 6 October 2020

After two decades equating budget surpluses with good economic management, it might seem convenient that the federal government has changed its fiscal strategy just before the budget to focus on jobs over keeping the deficit in check.

But it’s the right move. The world has changed in ways that make government spending more necessary and government debt more sustainable than ever.

Debt talk still dominates newspaper headlines and many of Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s media appearances. But it shouldn’t. Here’s why.

We are in the middle of a major economic shock

The COVID-19 recession is the biggest economic shock since the Great Depression. GDP fell 6.3% in the year to June, the worst annual result since 1929.

The federal government should use its balance sheet to spread the costs of such a large shock over time. The alternative would be to leave those who lost their jobs or businesses in poverty.

The government’s emergency response saved businesses and jobs from going under in the short term. Now, as we emerge from the crisis into the recovery phase, large-scale stimulus is needed to boost demand and create new jobs.

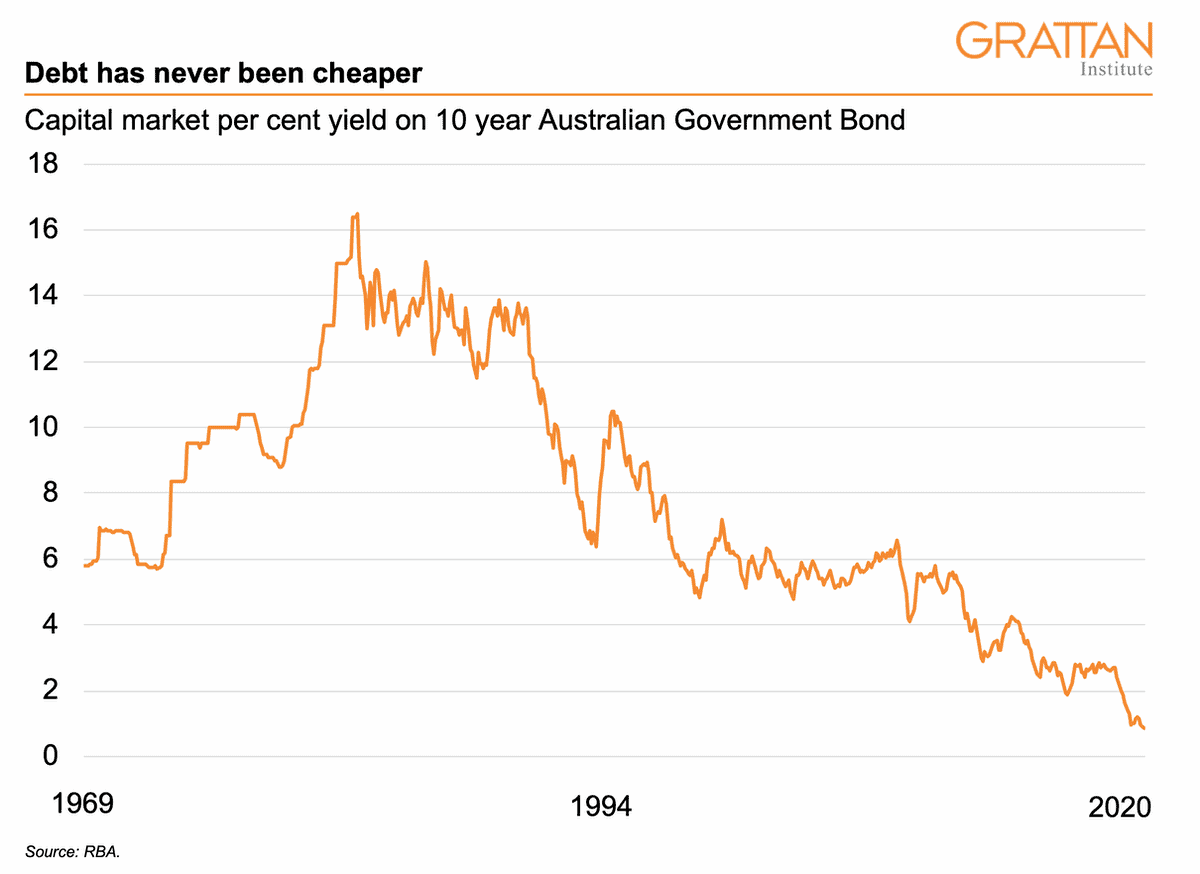

Debt has never been cheaper

It has never been cheaper for governments to borrow. As the next chart shows, the interest rate on 10-year Australian Government Bonds is less than 1%. If inflation stays above 1%, as the Reserve Bank and Treasury expect, the “real” interest rate the federal government pays on the bond will be negative. That is, it will effectively be paid to borrow.

These very low interest costs change the dynamics of managing debt we accrue now. Investments that boost future growth – including spending to reduce unemployment and close the output gap – will pay for themselves.

This is the fiscal “free lunch” spoken about by the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, Olivier Blanchard, and the deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Guy Debelle.

Extra stimulus won’t spook financial markets

To get the unemployment rate below 5% by the end of 2022, the Grattan Institute estimates a further A$100 billion to A$120 billion of fiscal stimulus is needed on top of what governments have already announced.

This is unlikely to cause financial markets to break a sweat. Even if gross debt was to nudge 50% of GDP in the next few years, it would still be far below that of most other developed nations before the COVID crisis. At the end of 2018-19, the gross public debt in the UK was 85% of GDP, in the US 103%, and in Japan more than 200%. All have borrowed substantially more since then at very low rates.

There’s also no risk that significant government spending will cause wages or inflation to rise dramatically. In fact, Australia has the opposite problem. Wages were stagnant before the crisis and are forecast to remain so for years. Inflation has been persistently below the Reserve Bank’s inflation target and is forecast to remain so for years.

We can manage debt without austerity

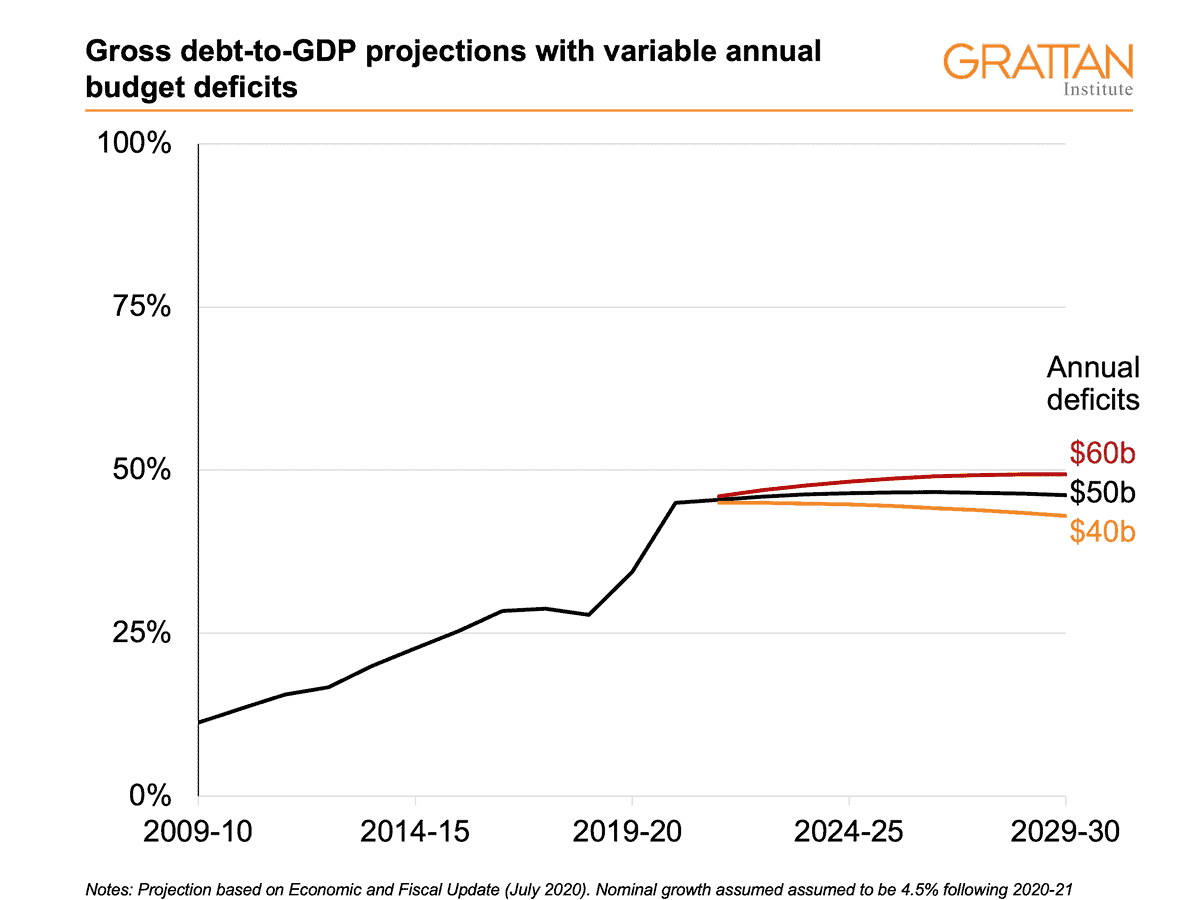

Frydenberg has signalled that, as employment recovers, the government’s fiscal strategy will shift to stabilising and then reducing debt as a share of GDP. Although his stated threshold of “well under 6% unemployment” is not ambitious enough, the idea makes sense.

The good news is that with interest rates on government borrowing so low, debt as a share of GDP can be reduced without pursuing austerity in the form of deficit reduction.

The interest rate is one of three factors that affect the size of debt relative to GDP. The other two are the budget balance (the incremental contribution to debt) and nominal GDP growth, which depends on economic activity and inflation.

Even if interest rates were a little higher than now (say, 1.5%), the government can reduce debt relative to GDP even while continuing to run large deficits, provided that nominal GDP growth returns to a moderate level (say, 4.5%, as it was before the pandemic).

The next chart shows that under these circumstances the government can run deficits of up to $50 billion and still reduce debt as a share of GDP.

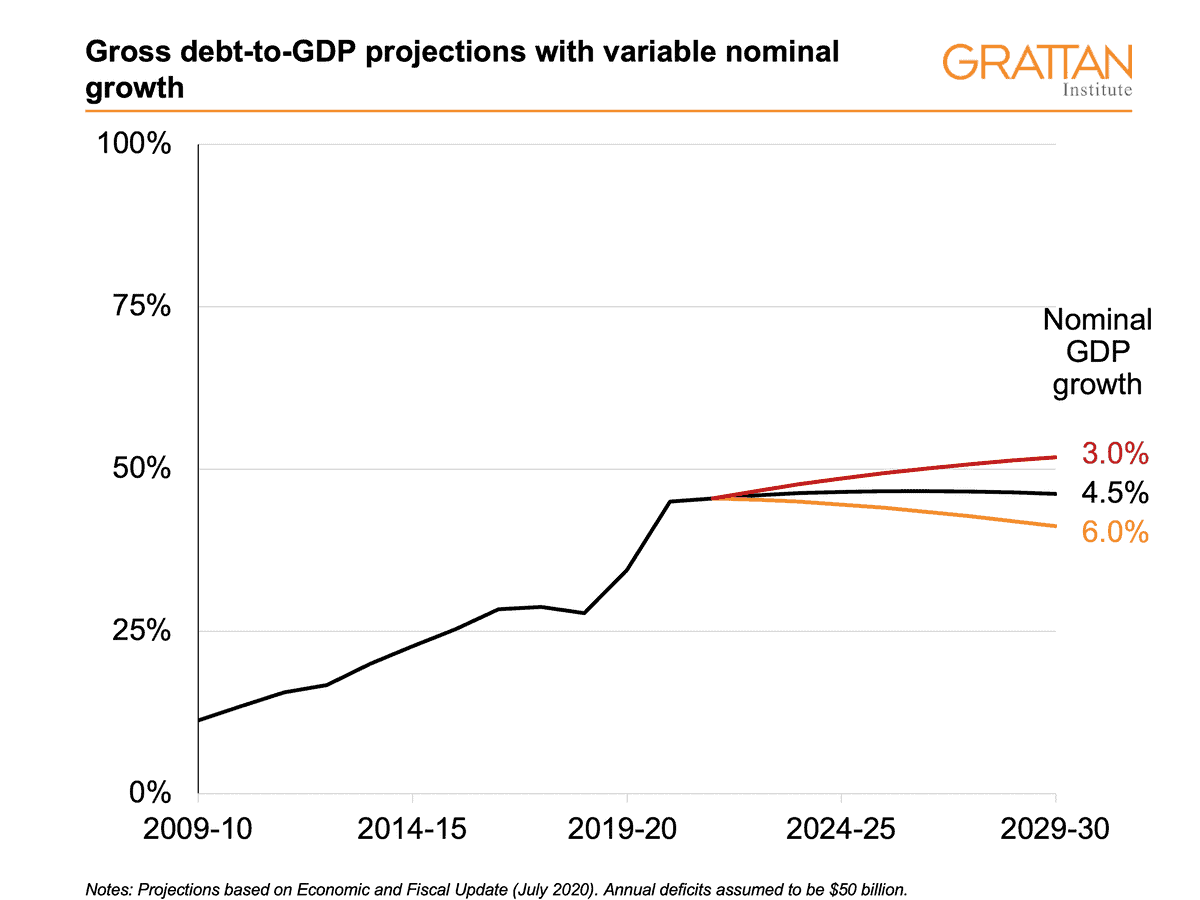

Different rates of GDP growth would change this story, as the next chart shows. With an even higher nominal growth rate, debt would shrink even faster relative to GDP. In a scenario of prolonged low growth, debt would increase relative to GDP a little, but remain very modest.

The government can do things to boost nominal growth in areas such as tax reform, education and skills, workforce participation, energy and climate policy, and land-use planning. The Reserve Bank should also do more by boosting inflation, which would support nominal growth.

Don’t scrimp on stimulus

There are many urgent and valuable priorities for government spending right now, such as permanently raising JobSeeker, boosting child-care support and building more social housing.

More debt might impose a small cost over a very long time. But the cost of insufficient stimulus and a prolonged recession would be vastly bigger.

The choice is simple. We should not let debt panic distract us from making it.

![]()