5 steps to better specialist healthcare

by Peter Breadon, Dominic Jones

How’s your health? Have you seen a specialist lately? If so, you probably faced an unenviable choice: pay a hefty fee to see a private doctor or endure a long wait in the public system.

This dilemma is symptomatic of a system that’s been left on autopilot for far too long. The federal government has thrown the kitchen sink at improving access to GPs. Specialists – who bulk-bill less, charge much more, and have longer wait times – have mostly been left in the too-hard basket.

Meanwhile, chronic disease is on the rise. Half of us now live with at least one chronic disease, and one in five Australians have two or more. As our health needs become more complex, specialist care is more important than ever. But seeing a specialist is getting harder.

Since 2010, the cost of a specialist consultation has grown by over 70 per cent. In 2023, an initial consultation with a psychiatrist would typically have left you nearly $250 out of pocket. Unsurprisingly, nearly a million people skip or delay specialist care because of the cost.

If you can’t pay, you’ll have to wait. Across Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide, there are 50 types of specialty – such as cardiology and paediatric medicine – where public wait times are over a year.

High fees and long waits mean nearly two million Australians are delaying or skipping care that their GP has recommended. That can lead to missing a crucial diagnosis or treatment, and more intensive – and expensive – care down the track.

Governments need to take charge. The specialist system needs comprehensive reform to tackle training bottlenecks, failures in planning and investment, inconsistent public services, and outrageous private fees.

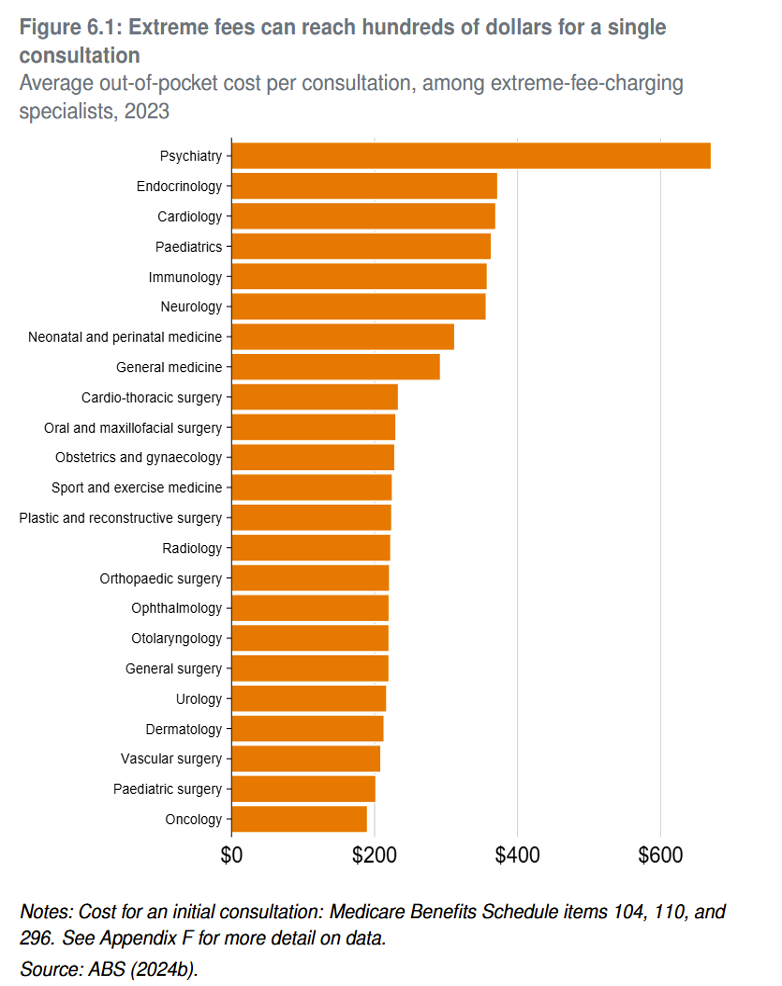

There’s nothing to stop some specialists charging extremely high fees that can be double or triple the fixed schedule fee that Medicare covers.

The first step is training the workforce Australia needs.

For decades, we had too few of some kinds of specialists – such as psychiatrists and dermatologists – and too few specialists overall in rural areas. But there are no clear targets for how many specialists Australia needs, and most training funding is not linked to filling the gaps. Instead, training has been largely based on precedent, and the priorities of specialist colleges and hospitals.

Governments should establish a workforce planning body, boost training funding, and tie funding to that body’s recommendations about what specialist training is needed, and where.

The second step is beefing up public clinics to fill the gaps left by the private market.

For many Australians, private specialists are simply too expensive, or too far away. People in the worst-served areas, such as Wide Bay in Queensland and western Tasmania, get about a third fewer services per person, compared with the best-served areas, such as eastern Sydney. Government investment is driven by inertia, not need.

Better clinics

Essential healthcare shouldn’t be a postcode lottery. Governments should commit to a national minimum level of specialist services and targeted public funding. They should provide around one million extra public appointments each year in the worst-served areas.

The third step is to make public clinics more productive.

There are big differences in how clinics are managed in different hospitals. Evidence suggests there is room to improve, such as by changing workforce roles, improving scheduling and triage, and using technology better. Governments should modernise public clinics by clarifying their role, facilitating the spread of best practices, and publicly reporting waiting times.

The fourth step is to take pressure off the system by helping GPs to do more.

Many costly referrals to specialists could be managed by GPs if they had access to some quick advice. All states should – as Queensland has done and as WA is planning to do – set up a system that allows GPs to easily consult other specialists. This could avoid 68,000 referrals annually and save patients $4 million in out-of-pocket costs.

The final step is to address the exorbitant fees charged by some specialists.

Specialist care is not a normal market. There’s little competition in many parts of Australia, and no easy way to tell good care from bad. Fees are totally unregulated. There’s nothing to stop some specialists charging extremely high fees that can be double or triple the fixed schedule fee that Medicare covers.

The federal government should claw back public subsidies from the 4 per cent of specialists who charge more than triple the schedule fee on average – fees so high that they can’t possibly be justified by higher costs of delivery, or higher quality care.

Specialist care needs an overhaul. Bottlenecks and cost blowouts are hurting Australia’s health and productivity. As the population ages, the problem is only going to get worse. With the National Health Reform Agreement under negotiation, now is the time for federal and state governments to come together and set specialist care on a better course.