*An edited version of this article appeared in The Conversation, Tuesday 13 March

Bill Shorten has announced that Labor will abolish cash refunds when investors, such as retirees, who pay little or no tax get dividends from companies that have paid company tax. It’s not first-best comprehensive tax reform. But in the absence of that holy grail, it is a piecemeal move towards a more equitable tax system that collects enough revenue given current spending commitments.

Australia’s dividend imputation system was designed to stop shareholders having to pay tax twice on corporate profits. When a company pays tax, it generates franking credits that can be attached to dividends. When dividends are paid, Australian shareholders can offset the tax already paid by the company against their personal income tax.

Cash refunds were introduced in 2001 for shareholders who had more franking credits than the tax they owed. The theory was that people will no or low income should have the same incentives to invest in Australian companies as other investors. At the time, the decision cost the budget little – around $550 million a year – because very few people with low income also owned shares.

But things have changed and the decision now costs the budget more than $5 billion a year. In 2006 new superannuation rules relieved retirees from paying any tax on their superannuation withdrawals – which had effectively been a tax on earnings. An increasing number qualify for this benefit as more people with significant super balances retire. And a series of changes to the Seniors and Pensioners Tax Offset increased the proportion of over-65s paying no tax on earnings outside of super.

Labor proposes to abolish cash refunds for individuals and superannuation funds (not-for-profits and universities, which do not pay income tax, will continue to receive cash refunds for franking credits). Of the $5 billion a year in extra revenue, about 33 per cent will be paid by individuals (presumably mostly retirees with some of their investments held outside of super), 60 per cent will be paid by self-managed superannuation funds (typically held by wealthier retirees), and the remaining 7 per cent will be paid by APRA-regulated superannuation funds.

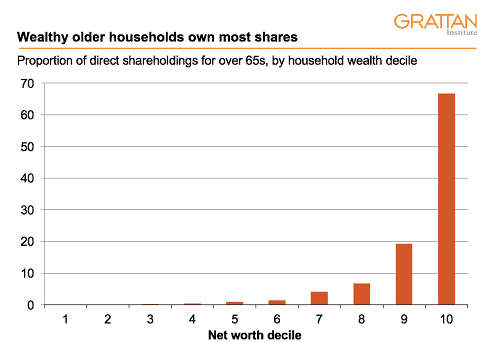

The change will primarily affect wealthy retirees. The wealthiest 20 per cent of Australian retirees own 86 per cent of shares owned by retirees outside of super funds. And among self-managed superannuation funds (primarily held by wealthier retirees), half of the refunds are currently going to people with balances over $2.4 million.

ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2015-16

ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2015-16

But there’s no free lunch. The franking credit regime was set up for a variety of good reasons. It aimed to bias Australians towards investing in Australia. In practice this appears to have led to Australian companies being funded more through equity and less through debt, improving financial stability. In theory it would also lead to more physical investment in Australia, although there’s less evidence of this in reality. In practice, franking credits also encourage Australian companies to pay dividends rather than inefficiently hoard cash or invest in low-return projects. While some claim that these effects just provide above-market returns to domestic investors because prices are set by international investors, the better view is that prices are influenced at least in part by domestic investors.

The positive effects of the franking credit regime will be weaker if retirees don’t get a cash refund for their franking credits. But it will still have a big effect because it will continue to influence the behaviour of those investors who do pay some income tax.

So abolishing cash refunds, but keeping franking credits for those who do pay income tax, is probably not first-best policy. It abandons the principle that all company profits should be taxed at an investor’s marginal rate of income tax. And it reduces the incentive for retirees to invest in companies from Australia rather than overseas.

On the other hand, abolishing cash refunds may well be a reasonable second-best policy in a tax system rife with distortions. The decisions not to tax superannuation withdrawals and to increase the effective tax-free threshold for older Australians have led to wealthy retirees contributing very little to government revenues relative to younger households. Even though the wealth of older generations has jumped in line with asset prices, the share of senior Australians that pay income tax has nearly halved – from 27 per cent to 16 per cent – in the past two decades. People over 65 pay less income tax per household in real terms than seniors did 20 years ago, despite their rising incomes and workforce participation rates. Yet recent attempts to repair the budget have focused overwhelmingly on younger Australians.

A first-best policy would reintroduce a number of higher-income, higher-wealth older Australians to the tax system by taxing superannuation earnings and abolishing age-based tax rates. But in the absence of the political will to make these changes, abolishing cash refunds provides a big boost to the budget bottom line from more or less the same group.

In a world where the appetite for wholesale tax reform has stalled, the government has been running sizeable budgets deficits for almost ten years and the income tax burden on working Australians continues to rise, a policy that indirectly requires richer older Australians to contribute may be the best we can do.

![]()