Australians are pretty healthy, on the whole.1 In the health chapter of the 2019 Commonwealth Orange Book, we show that a baby born in Australia can expect to live 82.5 years. That’s a longer life expectancy than in almost all of the comparator countries we included in the Orange Book – only Japanese babies can expect to live longer than Australians.

But is this the right way to compare health outcomes across countries? Life expectancy is a pretty crude measure of health – it doesn’t take into account what happens to people while they’re alive. If two countries have the same life expectancy, but people in one country can expect to spend a larger proportion of their lifetime unwell, then life expectancy doesn’t tell us anything about this important difference between the countries.

There are other, more sophisticated, measures of health outcomes that do take into account how healthy people are while they’re alive, not just the expected length of their lives. The good news for Australia is that we look pretty good on those measures as well.

‘Health-adjusted life expectancy’ is a more sophisticated measure of health outcomes. This measure shows the number of years that a baby born today can expect to live in good health. Australia’s life expectancy is 82.5 years, but our health-adjusted life expectancy is 71.9 years, indicating that a baby born today can expect, on average, to spend some of their life in poor health.

Australia isn’t alone in having a gap of around 10 years between life expectancy and its health-adjusted counterpart. The two measures of health outcomes are very closely related – countries that rank high on life expectancy tend to also have high health-adjusted life expectancy.2

If we had used health-adjusted, rather than raw, life expectancy in the Commonwealth Orange Book, the story would’ve been changed a little, but not a lot. Given the noise and uncertainty that goes along with measuring health status, we shouldn’t make too much of small differences between countries. Australia’s life expectancy is among the very highest in the OECD – we rank a little worse on the health-adjusted measure, but we’re still in the upper echelon.

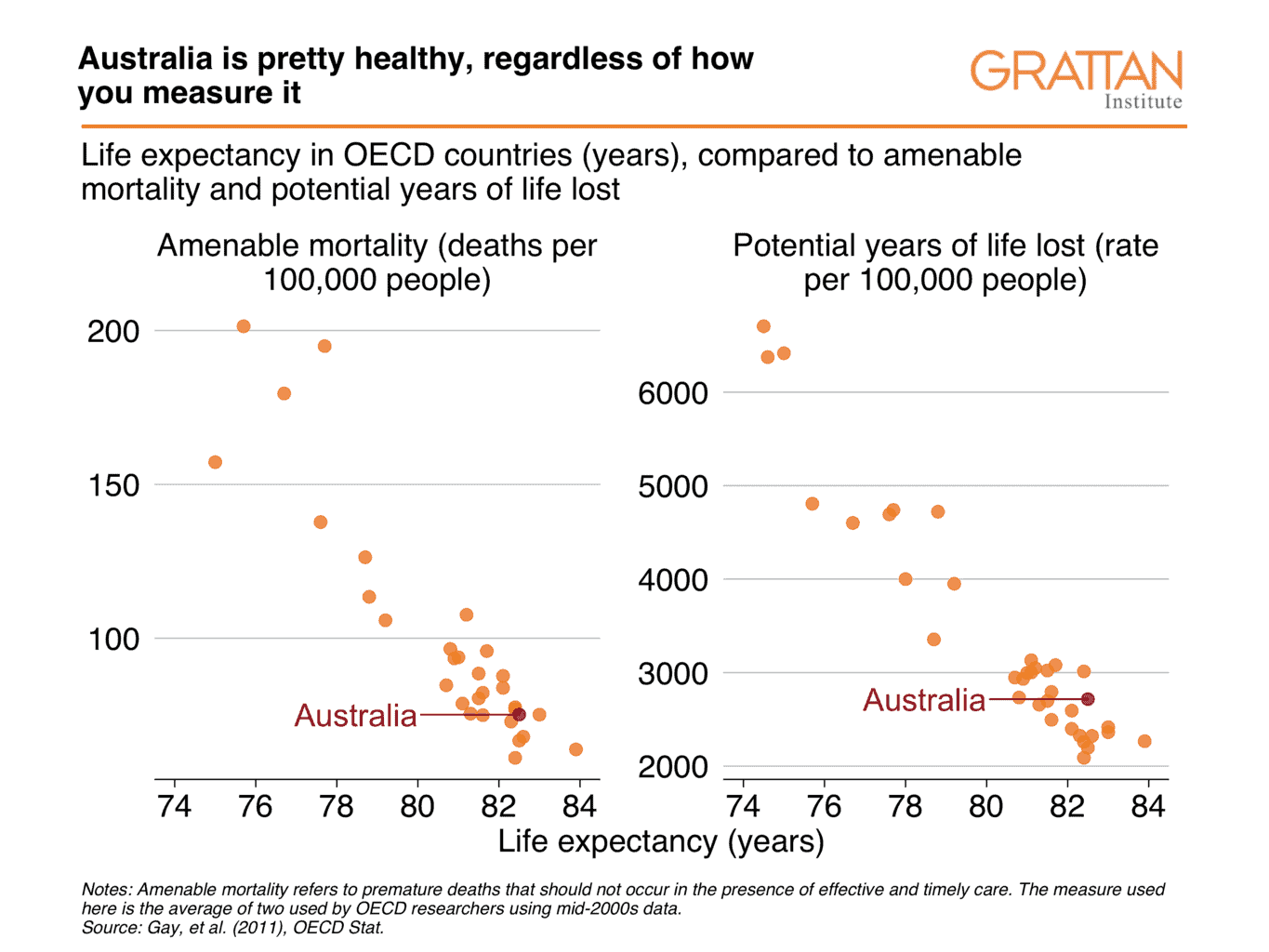

Other measures of health outcomes tell a similar story. Amenable mortality – which measures how many people per 100 000 in the population die from diseases that could potentially have been prevented given effective and timely health care – tends to be low in countries with high life expectancy. Australia fits that pattern. In Australia, there are 75.2 deaths each year that might have been prevented if people had received good health care when they needed it.3 That’s among the lowest rates of amenable mortality in the world.

Another measure of overall health outcomes that is often used is ‘potential years of life lost’. This is an indicator of premature mortality – how many people die young, weighted by how young they die. For the purposes of the OECD statistics, a death before the age of 70 is counted as a premature death. So, if someone dies at 65, there are five potential years of life lost; if someone dies at 20, there are 50 years lost. Adding up all the years lost through people dying young gives a country’s total potential years of life lost.4

Just as with amenable mortality, there is a strong inverse relationship to life expectancy: countries with long life expectancies have low levels of potential life lost through premature death. Australia fares well on this measure, too. For every 100 000 Australians, there were 2716 years life lost to premature death in 2016, which is towards the upper end of OECD countries.

Amenable mortality and potential years of life lost are both closely related to life expectancy and to each other – as you can see in the graph below, countries that do well on one measure do well on the others.

Other measures – like infant mortality, or the proportion of the population who say they’re in good health – also tell a similar story. Most countries with high life expectancy tend to do well on these measures, though the relationship is weaker than it is with health-adjusted life expectancy, avoidable mortality, or potential years of life lost. Australia fares fairly well on all of them.

We should be careful not to conclude that good health outcomes are solely, or even mostly, due to the health system itself. A range of other social and economic factors have a big effect on how health people are. But – setting aside that important caveat – Australia’s health outcomes are among the best in the world, and the health system can take at least some of the credit for that.

For the Commonwealth Orange Book, we wanted one metric that would adequately capture Australia’s health outcomes. We went with life expectancy, partly because it’s widely understood and easily explained, and partly because recent data is available for all OECD countries. But if we’d chosen another measure, the story would’ve been much the same – on average, Australians are among the healthiest people in the world.

Footnotes

1. Of course, not all Australians are equally healthy. The gap in life expectancy and other health outcomes between Indigenous and other Australians is shocking, and we have a gap between the health of the rich and the poor.

2. Among OECD countries, the correlation coefficient between raw and health-adjusted life expectancy is 0.91 (calculated using Spearman’s rho).

3. The amenable mortality figures are from 2007, the latest year for which the OECD has published estimates for all its member countries. The figures used in this post are the average of the two amenable mortality measures included in the OECD analysis. The age of the OECD-wide amenable mortality statistics is one reason why we didn’t use them as a summary measure of health outcomes.

4. There are newer, more sophisticated ways of calculating potential years of life lost which don’t use a static upper age limit; the OECD uses the ‘subtract from 70’ method described here.