Published at The Conversation, May 11 2020

Australia has an historic opportunity to build a new, export-focused manufacturing sector based on renewable energy.

As a bonus, it could enable a less politically fraught conversation about climate change. Global action on climate change is in Australia’s national interest.

The changing climate is already reducing profits for Australian farmers. Tens of thousands of jobs depend on the again-bleached Great Barrier Reef.

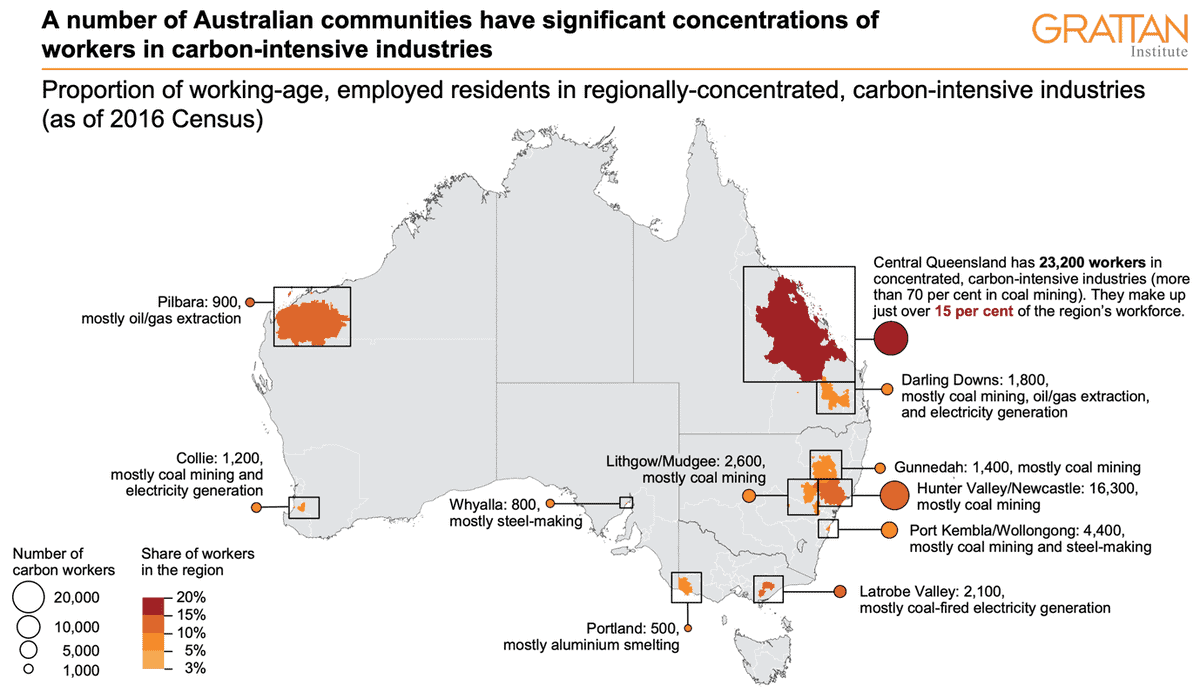

But for too long, political leaders have struggled to balance the national interest with the legitimate concerns of Australians who live and work in regions that host coal mining and other carbon-intensive industries – most notably central Queensland and the Hunter Valley in NSW.

This climate conundrum has greatly complicated the national debate about climate change: neither commitments to a “just transition” to a low-emissions future, nor promises of coal exports in perpetuity, have proven convincing, leaving regional jobs in the lurch.

Australians want industry

In the 2019 federal election, voters in these carbon regions, perhaps fearing for their livelihoods, seemingly rejected Labor’s more ambitious climate policies.

But with 85% of our black coal exported each year, decisions made in Beijing and New Delhi matter more to these communities than decisions made in Canberra.

Australia needs a credible plan to replace carbon jobs as the world decarbonises, and ideally the new jobs will offer similar salaries, need similar skills, and be located in similar places.

This is the key to cracking the climate conundrum: a plan based on sound economics that can offer hope to communities that currently depend on carbon-intensive activities.

A new Grattan Institute report, Start with steel, finds that manufacturing green steel for export is the largest job opportunity for these regions of Australia.

We can start with steel

Green steel can be made by using renewable energy to produce hydrogen, and then using that hydrogen in place of metallurgical coal in the steelmaking process.

The byproduct is water, rather than carbon dioxide.

Winding back the 7% of global emissions that come from steel production will require creating demand for low-emissions steel.

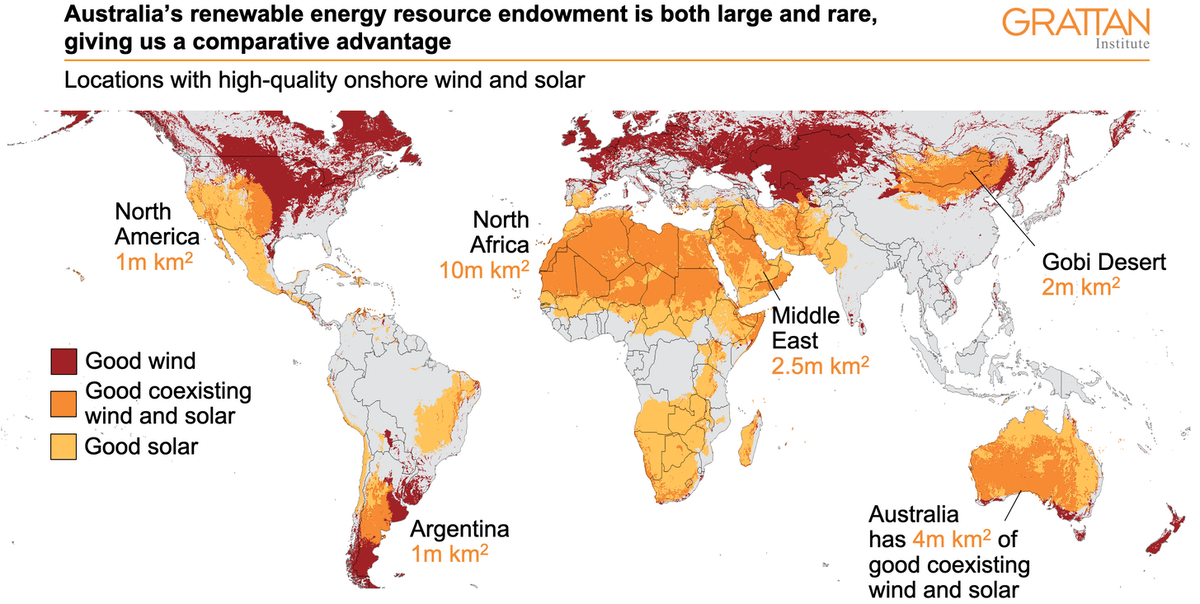

Australia has far better renewable resources than many of our major Asian trading partners, allowing us to make low-emissions hydrogen more cheaply, and therefore to make cheaper green steel.

And because hydrogen is expensive to transport, it makes sense to use it to make green steel here rather than exporting it to make green steel somewhere else.

The Pilbara in Western Australia is the world’s largest iron ore province, which makes it look like the natural place to make green steel.

But it is difficult to attract workers to remote Western Australia. Making green steel for export would require large industrial workforces like those in central Queensland and the Hunter Valley.

Our calculations suggest that the availability of reasonably-priced labour on the east coast of Australia more than outweighs the cost of shipping iron ore from Western Australia to turn it into green steel there.

If Australia captured just 7% of the global steel market, it could create 25,000 ongoing manufacturing jobs.

Seven per cent is much higher than the 0.3% of globally-traded steel that Australia produces today – but it is much less than our share of iron ore production, which is 38%.

Crucially, the opportunity does not rely on leaps of faith or endless subsidies – it is one of the few economically-credible ways to make the low-emissions steel the world will need if it gets serious about tackling climate change.

We should act quickly

There are also opportunities for Australia’s regions to manufacture biofuels for aviation and use renewable hydrogen to make ammonia.

The markets for these products are less certain, but if the world moves decisively to limit emissions, the projects that respond will deliver thousands of jobs.

Governments cannot single-handedly create these industries, and nor should they.

Instead, they should focus on bringing down the cost of the key intermediate product – hydrogen – by funding pre-commercial studies of geological structures suitable for storing hydrogen cheaply.

And they should invest in Australia’s low-emissions steel making capabilities by partly funding a flagship project that uses the direct reduction technology needed to use hydrogen to make steel.

The politics of climate change skewered a decade’s worth of prime ministers. And an inability to communicate the costs of action – and why they’re justified – contributed to a would-be prime minister losing an unlosable election.

Green steel offers Australia a reset button: a chance to get bipartisan cooperation to tackle a wicked problem that threatens our national interest.

We’ve heard plenty about the climate crisis. It’s time to talk about the opportunities.

![]()