Published in John Menadue – Pearls and Irritations, 11 June 2020

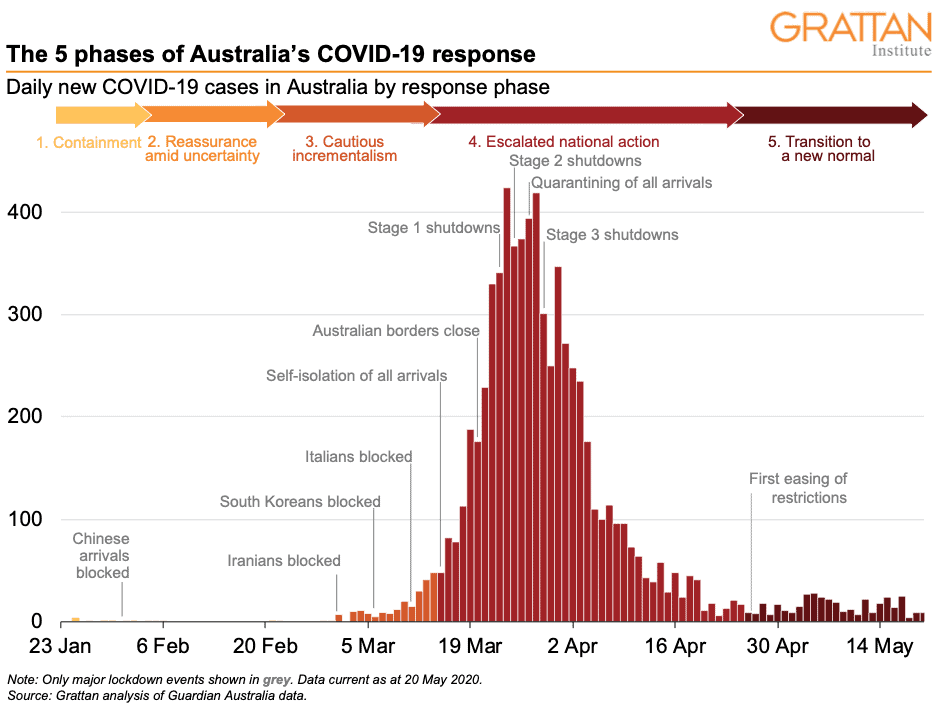

Australia’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been remarkably successful. After an exponential increase that peaked at more than 400 cases a day in late March, daily cases declined to almost zero a month later.

At the same time, rapid growth in infections in almost every other comparable country threatened to overwhelm their health systems. As Australia eases its restrictions, it is time to reflect on what happened.

The initial outbreak

In late December 2019, China notified the World Health Organisation (WHO) of a mysterious pneumonia cluster. The disease that was to be named COVID-19 made its way into history. Cases in Hubei province grew exponentially: seemingly slow at first, then very rapidly from late January.

The Chinese Government responded on 23 January with a massive program of testing, contact tracing, and quarantining of people likely to be infected. The population of Hubei was required to follow stringent spatial isolation. Travel, industry, education, recreation, and social gatherings were severely restricted to prevent the spread of infection.

On 30 January, WHO declared the coronavirus a global Public Health Emergency, when China’s death toll reached 170 and 7,711 cases were reported in the country. Daily cases peaked at nearly 4,000 in February and then declined to less than a 100 by early March.

The virus spread internationally in mid-January, first to Thailand than to the US, Nepal, France, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea and beyond.

Australia’s five-phase response

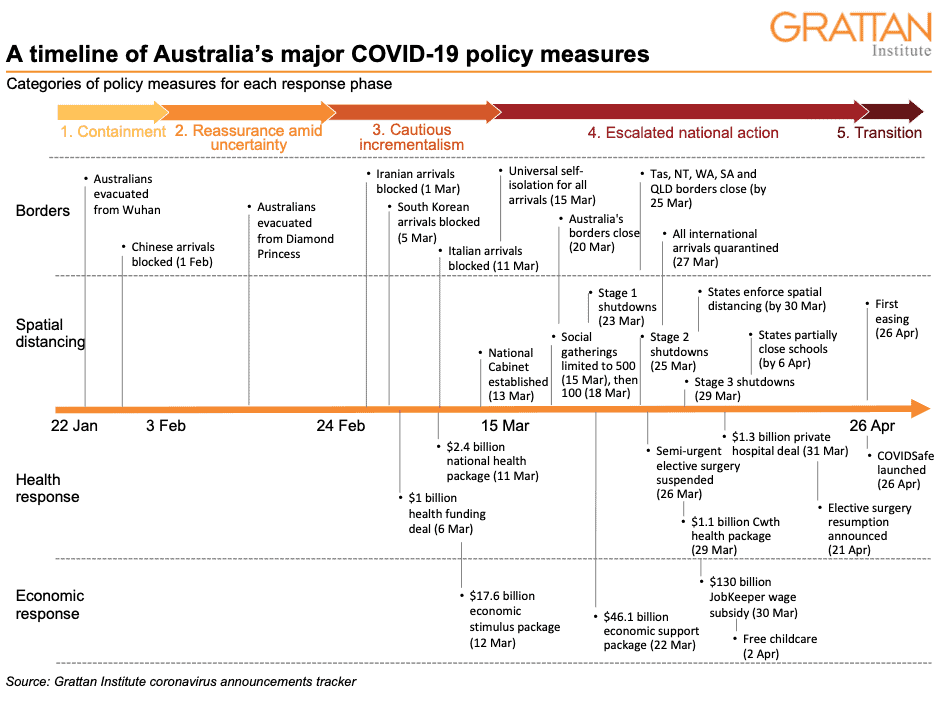

Australia’s response to the pandemic passed through four phases: containment, reassurance amid uncertainty, cautious incrementalism, and escalated national action. Australia has now begun entering a fifth phase: gradual transition to a new normal.

Phase 1: Containment

Australia recorded its first case on January 25, less than a month after the early cases were reported in China. During the early period of infection in Australia, the Commonwealth Government took main responsibility for managing COVID-19, acting on the advice of the Commonwealth Chief Medical Officer and the state and territory chief public health officers meeting as the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee.

The initial Commonwealth response was primarily focused on containing the external threat presented by the virus. During late January and early February, Australia’s first coronavirus cases were linked to travellers returning from Wuhan, China. The Commonwealth focused its efforts on screening arrivals from Wuhan and evacuating vulnerable Australians out of Hubei to designated, well-controlled quarantine facilities in Australia (such as Christmas Island).

As the virus rapidly spread in China to more than 10,000 confirmed cases by 1 February, Australia moved quickly – earlier than other countries – to ban foreign nationals entering the country from mainland China. It also required Australians travelling home from mainland China to self-isolate for 14 days.

Phase 2: Reassurance amid uncertainty

After introducing travel restrictions from China, the Commonwealth did not take any significant steps until late February. Instead, February was marked by uncertainty about the scale of the crisis, while the Commonwealth downplayed the risks to Australians.

With the exception of the outbreak of cases affecting Australians on the Diamond Princess cruise ship stranded in Japan, very few Australians contracted COVID-19 during February. At the same time, it appeared the major outbreak in Hubei had subsided and the number of cases in other countries remained low.

There was uncertainty about the susceptibility, incubation, duration, transmission, morbidity, and mortality of COVID-19. Data and research were changing rapidly, on almost a daily basis. In the absence of clear data and analysis, there was concern about the potential social and economic cost of widespread action to prevent the possible spread of infection.

Australia’s response was reinforced by advice from WHO. Although WHO declared a Public Health Emergency at the end of January, it did not consider travel or trade restrictions necessary. WHO emphasised containment based on detection, isolation, contact tracing, and information. It did not recommend mandatory quarantine of international travellers. Nor did it advise member countries to prepare broader spatial distancing measures and increase the capacity of their health systems, despite the experience in Hubei.

Australia’s Prime Minister, Health Minister and Chief Medical Officer rejected calls for extended travel bans and tighter quarantine for overseas travellers. Meanwhile, state and territory governments mainly continued business as usual, with the NT and Queensland launching international tourism campaigns after the summer bushfire crisis.

Yet COVID-19 cases were rapidly spreading in countries beyond China. South Korea had more than 1000 total cases by 26 February, Italy exceeded this number three days later, and Iran reported a doubling of its cases overnight to reach 1000 cases on 2 March. By this time, the virus had spread to at least 75 countries worldwide.

Amid the uncertainty, the Prime Minister sought to reassure Australians in early March that they could ‘go about their daily business’, and that he was ‘looking forward to going to places of mass gathering such as the football’.

But this message missed the mark. Community concern about the virus was reaching a tipping point, with Australians panic-buying toilet paper and other goods. By 2 March, Australia recorded its first case of community transmission, and Australia’s policy response was propelled into the next phase of policy action.

Phase 3: Cautious incrementalism

Throughout early March, the Commonwealth’s response shifted. It became clearer that COVID-19’s long incubation period and mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic infections made it difficult to prevent transmission. The action grew incrementally to introduce additional measures to ‘slow the spread’. The Government took cautious steps during this phase, careful to have a ‘proportionate’ response to specific high-risk countries.

Bans on foreign nationals entering Australia were extended to Iran, South Korea, and Italy in the first two weeks of March, as COVID-19 spread in these countries. Australian travellers from these countries were required to self-isolate for 14 days on arrival. When these bans were introduced, Iran had 978 cases (2 March), South Korea had 6,284 (5 March), and Italy had 12,462 (11 March).

By 15 March, when Australia had 300 confirmed cases, mostly from overseas arrivals, self-isolation was made mandatory for all international arrivals, although enforcement measures were weak. Health officials implemented contact tracing systems to reduce the risk of community transmission. Testing regimes, led by the states, began to get bigger. Australia had one of the highest testing rates per person in the world. By mid-March, more than 100,000 tests had been conducted.

In early March, the Commonwealth began preparing for the inevitable pressures on Australia’s health system and impacts on its economy. But the Government’s measures still appeared to underestimate the scale of the response required to combat the virus.

The Commonwealth made an uncapped health funding agreement with the states and territories on 6 March, agreeing to meet half the increased health costs of patients with COVID-19, with an initial Commonwealth commitment of $500 million. This was quickly followed by a $2.4 billion health package on 11 March, which provided funding to purchase more personal protective equipment and for other measures such as telehealth.

A day later, the Commonwealth announced its first (relatively small) economic stimulus package of $17.6 billion to support businesses and households. It did not include support for people who had lost employment because of business closures.

By early March, the states and territories also shifted their focus to COVID-19 and began to slowly announce a ramped-up public health response. In advance of the Commonwealth, Victoria released its pandemic plan. Some states began to set up specific COVID-19 testing clinics. South Australia established the first drive-through testing centre.

But by mid-March, it became clear that more was needed to restrain the emerging exponential growth of the virus.

Phase 4: Escalated national action

The second half of March was a turbulent period of significant change. Within two weeks, Australia transitioned into a full shutdown. Widespread spatial distancing measures were announced alongside broader travel bans, testing, contact tracing, and quarantine.

During this phase, debate centred on how far Australia should go; whether it should ‘slow the spread’, or go harder and ‘stop the spread’. The primary motivation was to protect Australia’s health system and prevent hospital intensive care units being overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients.

This phase started with pressure mounting on governments to take stronger action to reduce the risk of community transmission. Debate heightened about whether the Melbourne Grand Prix should go ahead on 13-15 March.

Because critical responsibilities – such as the imposition of spatial distancing requirements – are vested in state governments, the Commonwealth had no power to force any such changes. But there was no consistency among states in their approaches. It became clear that a national approach to coordination was needed, and on 13 March a new National Cabinet made up of the Prime Minister, Premiers, and Chief Ministers was set up and began to meet at least weekly to coordinate Australia’s response to COVID-19.

The first national spatial distancing announcement followed immediately on 13 March. Social gatherings were limited to fewer than 500 people. But the Commonwealth still hesitated on the precipice of change, when the Prime Minister sought to reassure Australians that the limit would only take effect after the weekend, during which he was still intending to go to the footy. Governments continued to move incrementally, limiting social gatherings to 100 people.

Australia’s case numbers began to increase exponentially, doubling every 3-to-4 days. Australians looked at Italy’s overwhelmed health system and feared that could be Australia’s fate unless stronger action was taken. Many Australians thought the Government was doing too little. Pressure mounted to introduce much tougher restrictions earlier to minimise the long-term damage. Further spatial distancing measures were announced, limiting indoor social gatherings to 10 people, and then, by the end of the month, to two people. Restrictions shut down all non-essential businesses and activities, and Australians were urged to ‘stay at home’. These measures were increasingly accepted by the Australian people.

It was also clear that a number of Australians returning from international travel had contracted COVID-19, particularly after travel in the United States and on cruise ships, the latter mostly from the Ruby Princess which docked in Sydney on 19 March despite having active cases on board. About two-thirds of Australia’s cases have come from overseas. It had quickly become clear that some returning travellers were not adhering to the self-isolation requirement and so eventually the Government further enhanced border controls on 27 March, to require mandatory quarantine in designated facilities for all remaining arrivals.

In their efforts to control the spread of the virus, some states and territories closed their interstate borders. Border restrictions started with Tasmania on 20 March, followed by the NT, WA, SA, and Queensland within a few days.

During this period of rapid change, inconsistencies in the messages and approach between the Commonwealth and the states began to emerge. The Commonwealth continued to take a more cautious approach to the introduction of widespread infection control measures. The states and territories, particularly NSW and Victoria, wanted more comprehensive measures such as school closures to prevent the spread of infection and to reduce the prospect that public hospitals, the responsibility of states, would be overwhelmed.

States and territories also rapidly increased their public hospital intensive care unit (ICU) capacity. Governments worked to prepare for the tripling of Australia’s ICU capacity, from 2,400 beds to 7,000. The Commonwealth allocated personal protective equipment from the national stockpile, while governments ordered more supplies, including ventilators, from overseas. The Commonwealth also boosted its public health funding with another $1.1 billion, including significant resources directed towards mental health care.

The Commonwealth refined its crisis governance structures to manage economic and social fall-out. It established a new National COVID-19 Coordination Commission, with leaders from the private and not-for-profit sector, to advise the government on how to limit the economic and social damage caused by the crisis.

Within 10 days, the Commonwealth rolled out two large economic support packages amounting to $176 billion of spending. These included the doubling of the JobSeeker payment (previously called Newstart), and a JobKeeper wage subsidy to keep people connected to their employer.

State governments began to progressively implement their own support packages for their local economies and industries, including grants, loans, and tax deferrals. These announcements amount to billions of dollars of spending nationally.

By the end of March, once the shock of the shutdowns had set in, the Commonwealth sought to cushion the blow by providing free childcare, and the National Cabinet announced a moratorium on rental evictions, to be implemented by the states and territories.

A range of health measures were also introduced. At the end of March, the National Cabinet temporarily suspended all non-urgent elective surgery in both the public and private hospital systems, to free up capacity to treat COVID-19 patients and to preserve personal protective equipment which was in short supply. In record time, the Commonwealth struck a $1.3 billion deal with private hospitals to underwrite them during the elective surgery shut-down, and states negotiated to buy the use of private hospital beds, including for the transfer of public hospital patients to private hospitals.

Because most of the COVID-19 deaths were among older people, new measures were imposed on aged care facilities. The number of visitors was restricted, as were resident movements, and staff were required to get vaccinated against the flu. The Commonwealth announced additional funding of $445 million for residential and home care services for older people.

Some states enhanced their spatial distancing measures, including effectively closing their public schools by bringing the Easter holidays forward. They also focused their attention on enforcing the restrictions, with police issuing hefty on-the-spot fines to people breaking the spatial distancing rules.

As Australians settled into the ‘new normal’ of stay-at-home life, their efforts were quickly rewarded in the case count: Australia appeared to be flattening the curve. New cases were rapidly falling; with an average daily new case rate of 70 over April. This was in stark contrast to some comparable countries such as the US and the UK, who struggled to get the virus under control.

This coincided with expanded testing, as new testing kits came into the market. At first, testing was limited to people who were showing symptoms and had recently been overseas or had had contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case. But then testing was expanded to health workers, people in high-risk areas, and people in known clusters, and then to any person showing symptoms. The aim was to capture community transmission. Some states went further still: South Australia and Victoria launched testing ‘blitzes’ to uncover remaining cases in the community. Victoria’s testing blitz aimed to test 100,000 people within two weeks; anyone with a cough was eligible for testing. By the end of April, more than half a million Australians had been tested for COVID-19, with an average positive testing rate of less than 1 per cent.

Phase 5: Transition to a new normal

After over a month of ‘stay-at-home’ life, governments began Australia’s transition to a new normal. Case numbers were dwindling to below an average of 20 new cases a day at the start of May, with some states recording successive days with no new cases. At this time, about 200 Australians were in the hospital with COVID-19, including about 30 people in intensive care units (ICUs); barely placing a burden on Australia’s healthcare system.

Governments finalised their preparations to manage the virus into the longer-term in a world with eased restrictions. This involved further boosting contact tracing capabilities and increasing testing to identify remaining cases in the community.

To assist with contact tracing efforts, on 26 April, the Commonwealth government launched its COVIDSafe app. This app allows health officials to more easily clamp down on community transmission. If a person with the app is diagnosed with COVID-19, health officials can trace the infected person’s contact with other people with the app. But downloading the app is voluntary, and commentators raised concerns that it invades their privacy or that the stored data could be misused. As of 8 May, over 5 million Australians had downloaded the app, well short of the Government’s target of 10 million.

But state government moved forward regardless, armed with the confidence of low case numbers. Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia were the first to announce small changes. This included the lifting of restrictions on national parks, and WA joining the NT in allowing gatherings of up to 10 people.

At the same time, the Prime Minister started to shift his rhetoric from concern about the health risks to concern about the economic fall-out from the crisis. The Government estimated the lockdown was costing Australia’s economy about $4 billion each week. The RBA expects that unemployment will top 10 per cent in the June quarter.

Building on the momentum to ease restrictions, on 8 May the National Cabinet agreed to a three-step plan and a national framework to bring Australia out of lockdown over the next few months. Step 1 allows outdoor gatherings of up to 10 people, small cafes and restaurants to open, and some recreational activities. Step 2 allows outdoor gatherings of 20 people and further businesses to open, and Step 3 allows gatherings of up to 100 people and remaining people to go back to work. International border restrictions will remain for the ‘foreseeable future’.

Within the national framework, state governments are ultimately responsible for deciding on lockdown restrictions. Each state government has announced the exact timing and content of the plan for their local jurisdiction. Some states like WA and the NT who have lower case numbers are moving faster than other states like Victoria and NSW, with higher case numbers.

And now moving forward

As restrictions unwind, a new norm will set in. The risk of COVID-19 emerging again means Australians’ way of life will have to fundamentally change. Some of these changes, such as telehealth, and options to work or study from home, are positive. But others, such as restrictions on travel, concerts, and major sporting events, less so.

Significant risks remain, particularly for states that ease restrictions too fast. Continual monitoring will be required to prevent further outbreaks or a second wave.

There is no certainty a vaccine or effective treatment will be developed. Even the most optimistic timeline is that this will take 12 months. While COVID-19 cases continue to occur, some restrictions will need to remain in place.