Published in The Conversation, 14 May 2020

At almost 10% of gross domestic product, and a much larger per cent of government spending, Australia’s fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis has been one of the biggest in the world.

The government is spending an average of A$26 billion a month on programs that didn’t exist in February.

To put that in perspective, before COVID-19 the government’s total average monthly expenditure this financial year was going to be $42 billion.

While far from perfect, these emergency measures have been successful at supporting the incomes of many households and businesses.

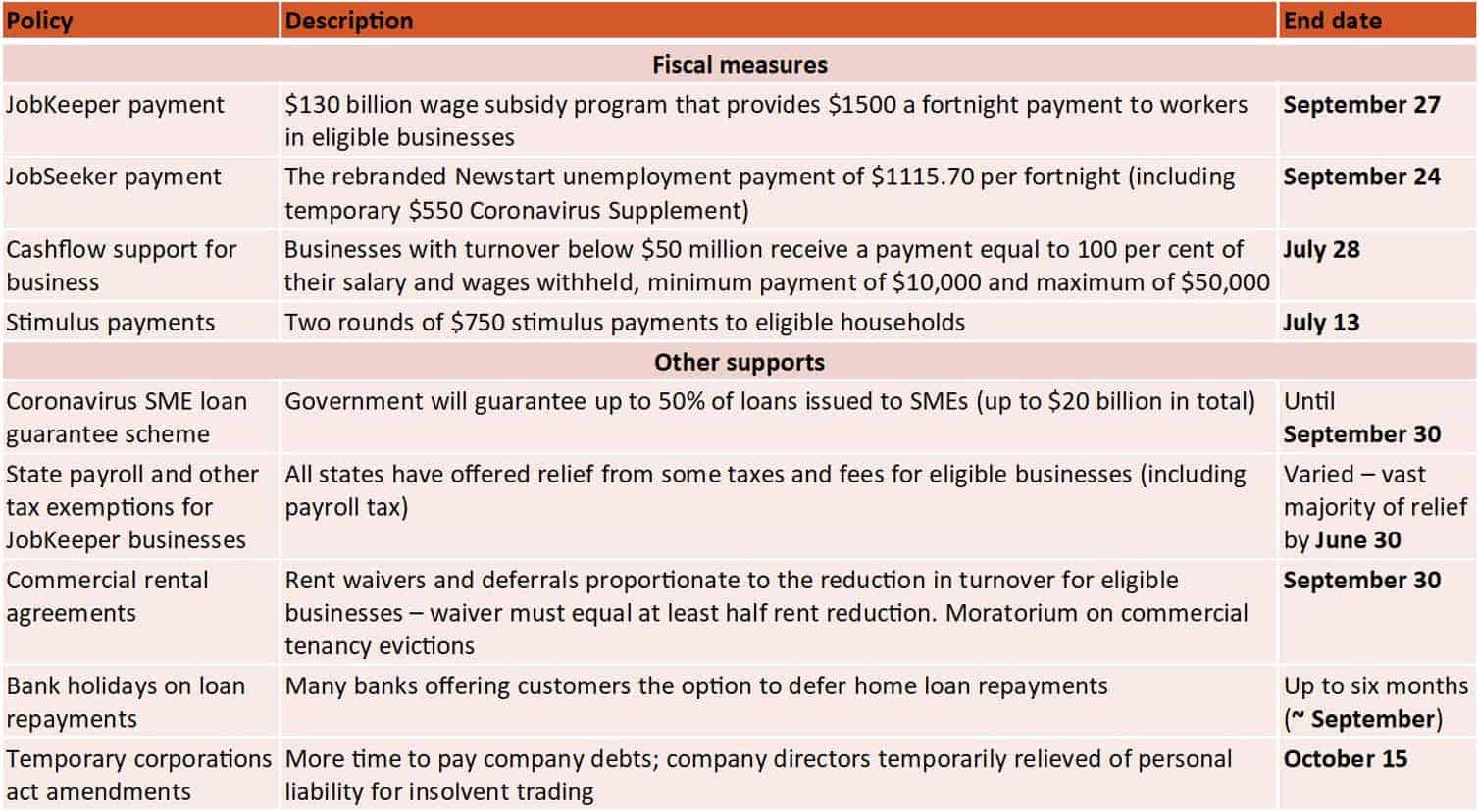

But, as this chart shows, each and every one will be gone by the end of October, making October a very dangerous time for businesses and for the economy.

In his address to parliament on Tuesday, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg spoke of a return to work as restrictions were eased.

But he noted that any new outbreaks of COVID-19 could see restrictions re-imposed at a loss of more than $4 billion per week to the economy.

Even if things go to plan, the harsh reality is that big parts of the economy are still likely to be doing less than they should for some time yet.

Most of the world has not fared as well as Australia in limiting deaths and the spread of the virus, which means global economic activity and demand will be weak for some time.

Businesses and consumers are likely to be cautious. Many will find themselves financially challenged because their loan and rent obligations were deferred rather than removed during the crisis.

Australia’s population growth will be much slower because of the reduction in temporary migration, hitting consumer-facing businesses and the broader economy.

Against this backdrop, the sudden withdrawal of massive government spending will leave an enormous hole in economy activity and the incomes of business and households.

The chart below shows that huge amounts of government support (more than 25% of gross domestic product) scheduled to vanish by the end of October.

It’s a recipe for a second downturn.

A much better approach would be to remove the measures slowly.

JobKeeper could be wound back in line with the recovery of individual businesses.

Reassessing eligibility after most physical distancing restrictions have been removed, particularly if the health situation is well controlled, seems sensible.

Support should end early for some, late for others

If the revenues of some businesses rebound to close to pre-coronavirus levels, they could come off JobKeeper early, before the September deadline.

But if the revenues of others remain weak because their operations are still constrained by health restrictions, the government could consider extending their JobKeeper payments beyond September.

Targeting support to the firms that need it most in this way would be a better use of taxpayers’ money – and it would help stop the economy falling off a “cliff” in late October.

The JobSekeer supplement could also be phased out more slowly than the government currently plans.

JobSeeker should stay higher than it was

The treasurer should settle on a new level of income support – lower than JobSeeker with the supplement but probably $75 to $100 a week better than JobSeeker without the supplement – so that people on it are spared significant financial distress while searching for work.

It could also announce a range of measures to boost demand in the danger zones that will be created by supports coming off.

There are plenty of good options.

- one-off cash payments to households, which we know have boosted spending

- more spending on mental health services or programs to help disadvantaged students catch up on learning lost

- infrastructure spending on shovel-ready projects with good returns to the community including social housing, roads and school maintenance

Debt will need to be managed over the medium term, but it shouldn’t constrain the government from implementing the policies needed to drive recovery.

On Wednesday the Office of Financial Management unloaded $19 billion of new 10-year bonds in the biggest bond sale in Australian history after receiving bids for more than twice that many.

It will pay an interest rate of 1.025%, which is less than the rate of inflation.

Transitioning the economy from emergency settings to business as usual will not be easy, but there’s no imperative to do it suddenly.

![]()