The biggest winners and losers from international education

by Brendan Coates, Trent Wiltshire

Australia’s international education sector is one of the country’s great success stories.

International students bring big benefits to Australia, first in the tuition fees they pay, and second, because many become permanent skilled migrants.

But not everyone wins from international education: the biggest losers are renters.

International education brings enormous benefits to Australia

Australia has one of the largest international higher education sectors in the world. Before COVID, international education services were Australia’s fourth-largest export, worth about $40 billion annually.

Getting the best international students to stay here permanently is even more valuable. International graduates account for one-third of our permanent skilled migrant intake.

Those students who are granted permanent skilled visas each year offer a $12 billion fiscal dividend over their lifetimes in Australia., That’s more than double the profits universities reap each year from teaching international students.

More international students means higher rents

While Australians overall are big winners from international education, there are also losers, and the biggest losers are renters.

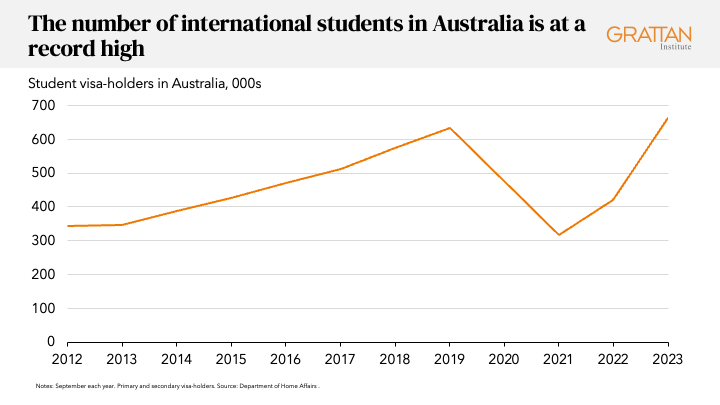

Most international students study for Australian degrees in Australia. International student numbers have surged since COVID to more than 650,000, well above pre-COVID levels and almost double where they were in 2012. Australia has more three times the number of international students, per head of population, than either Canada or the UK.

International students increase demand for housing which, because supply is limited, pushes up rents. We estimate that every 100,000 extra migrants in Australia raises rents by about 1 per cent.

The higher rents paid by international students to local landlords, compared to if that housing was otherwise rented locally, boosts national income because most homes that students rent are owned by Australians.

But by bidding up the rents paid by many Australians, international students also increase inequality in Australia. Higher rents benefit older, wealthier Australians, who tend to own housing, at the expense of younger, poorer Australians, who tend to rent.

We should boost Commonwealth Rent Assistance to compensate renters

When a nation like Australia wins big from international trade, but some residents lose, the solution is clear: we should ensure the losers from trade aren’t left worse off.

If we don’t act, it could lead to higher rates of homelessness, resentment towards migrants, and reactionary migration policies that would make Australia poorer.

It’s just one more reason the Albanese Government should further raise Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Last year’s 15 per cent increase should be turned into at least a 40 per cent increase. That would provide an extra $1,000 a year to nearly one-third of all renters, at a cost to the budget of about $1.2 billion a year.

We should fund it via higher fees on student visas

An increase in Rent Assistance should be paid for by an increase in student visa application fees, from $710 to $2,500 per visa.

Others have suggested applying a levy to international student fee revenues, or to all university revenues. But, unlike a levy, the Home Affairs Minister can raise visa fees with the stroke of a pen, increasing revenue almost immediately.

A levy would penalise our top-tier universities that are most attractive to international students, whereas higher student visa application fees would also discourage the growing number of international students who complete cheaper, low-value courses from coming to Australia.

Many students studying less-valuable course provide little economic benefit to Australia, because they pay much less in course fees, struggle to find well-paid work once they graduate, and are unlikely to secure a permanent skilled visa. Few are learning the skilled trades that we desperately need to build more homes.

A visa application fee rise is unlikely to discourage talented students from choosing to study at one of Australia’s top universities – those who we most want to stay permanently – because they already pay upwards of $150,000 for a bachelor degree.

Whereas the main lever the government is using to slow student numbers – ramping up rejections of student visa applications from some countries, which is mostly affecting lower-tier universities and many VET providers – is both opaque and indiscriminate, and appears to be capturing some high-value students who we want to study in Australia.

Student visa approvals have been running at well over 90 per cent for the past 15 years, but they hit a low of 82 per cent in the six months to December 2023.

Canada has just announced it intends to cap the number of international students, and Australia’s Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil hasn’t ruled out introducing a cap here. But that is too blunt a tool. The government would have to decide how many international student places would be allocated to each university. And imposing a cap would run the risk that many of the high-quality students that Australia wants to attract would go elsewhere, because it could prompt a rush of applications and therefore a delay in processing them.

Australia’s international education sector delivers huge benefits to Australia, but it also leads to higher rents, hurting vulnerable Australians. Raising Rent Assistance would ensure those people aren’t left worse off. Increasing student visa application fees help to manage student numbers and ensure continued support for international education in Australia.

The government should do it now.