Budget 2025: the health verdict

by Peter Breadon, Elizabeth Baldwin

An election year budget is usually a cash splash, and this time is no different. The Government is targeting cost-of-living concerns everywhere from tax to energy. In health, the focus is on subsidies for GPs and medicines.

The biggest spend is an $8 billion investment to boost bulk billing, which had already been announced, and which aims to help make nine in ten visits to the GP free by 2030.

The bulk-billing incentive – which was tripled a year ago – will go to GPs who bulk bill any patient, instead of only children and people with a concession card. And clinics that bulk bill all their patients will be eligible for a 12.5 per cent increase in their Medicare rebates. The changes will cost $1.2 billion in 2025-26, increasing to $2.4 billion per year ongoing.

Another pre-announced measure was cheaper patient payments for PBS medicines. The maximum co-payment will fall from $31.60 to $25. That fee, along with the current payment – $7.70 – for people with a concession card, will be capped until 2030. This change will cost a little over $200 million a year.

Another 50 urgent care clinics were funded – another pitch for fee-free care – along with more for women’s health, $1.8 billion more for public hospitals, and some smaller initiatives. Almost all those measures had been announced beforehand too.

An unaddressed cost-of-living challenge

Patients will probably welcome the cost-of-living relief, and there are signs that it is needed.

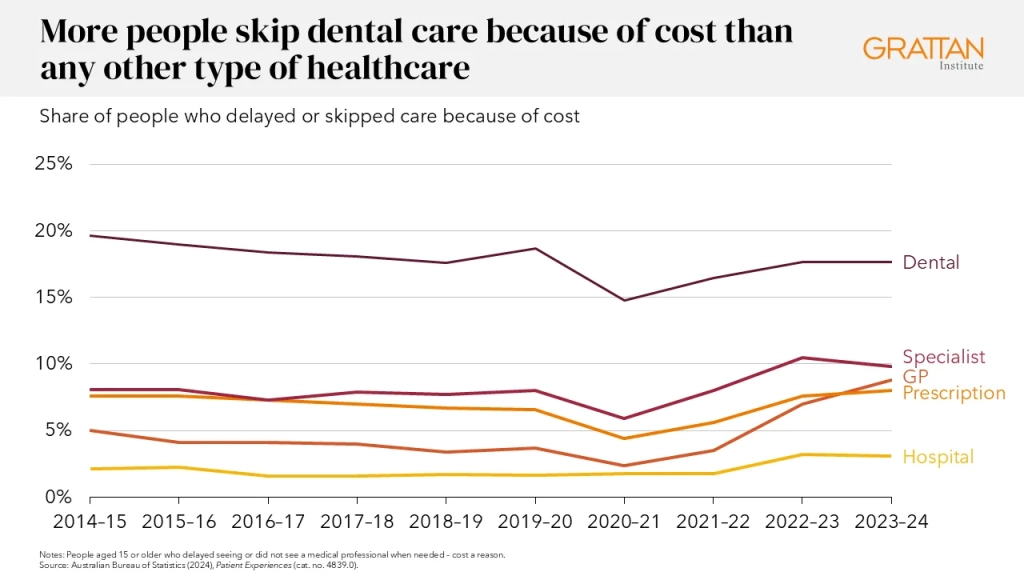

Before the pandemic, the share of people skipping a visit to the GP because of cost was usually well below one in 20. By 2023-24, it had doubled to almost one in 10.

There has been a smaller rise in people skipping prescriptions, with eight percent now putting off their pills because of cost, just above the level of a decade ago.

The Budget will probably help arrest both of these recent increases. But it won’t help with the much larger, and more persistent, cost barriers elsewhere in the healthcare system.

Dental visits hit many people’s hip pocket harder. Twice as many people say they are avoiding the dentist – compared to the GP or pharmacy – because of cost.

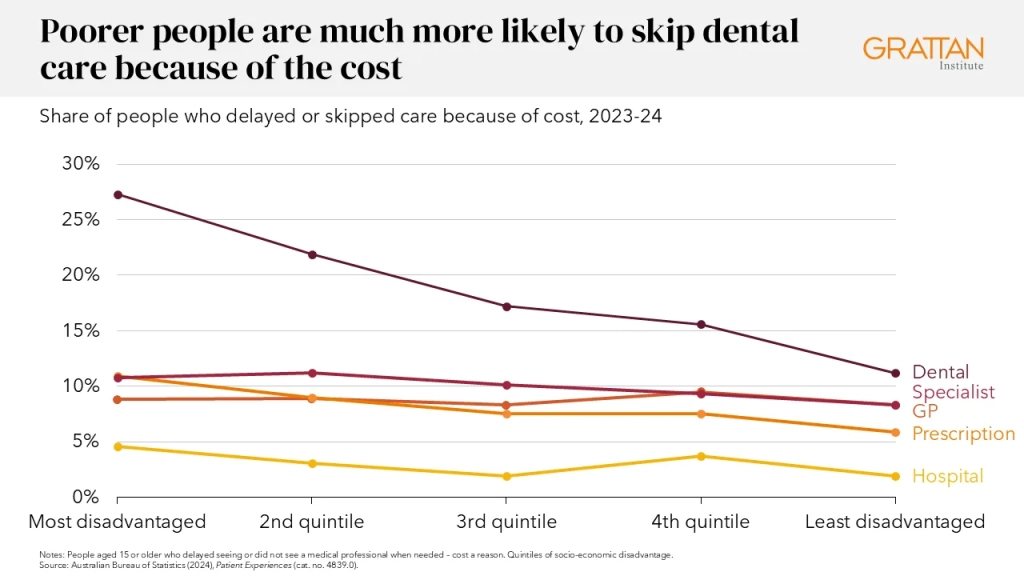

And as with other cost-of-living challenges, the poorest are hit hardest.

More than one quarter (27 per cent) of poorer people are missing out on dental care, far more than for any other kind of care.

That’s a big reason why dental health is decaying, and why visits to hospital for avoidable dental health problems have reached a record high.

The root problem is that dental care has never been part of Medicare. Putting the mouth into Medicare is part of the Greens’ election platform, and it has been championed by some Labor backbenchers.

But what is perhaps the worst cost of living pressure in healthcare was not addressed in this year’s Budget, beyond a short-term roll-over of federal funding for public dental clinics.

Neither was the affordability of mental health or non-GP specialist care.

The ‘cost-of-leaving’

The Government is spending a lot to reduce costs for patients, but the Budget is light on health reforms to make care more efficient and effective, or to prevent illnesses in the first place.

Every day of reform delay means more pressure on the health system in future.

More money for bulk billing, and new GP training places, will increase funding for primary care, which is important to meet the growing need for chronic disease management. The extra funding for public hospitals is also needed to help meet rising demand for care.

But most of the recommendations in several sweeping reviews of primary care, and in a damning review of hospital funding and national health reform, have not found their way into major budget investments.

And while funding was previously set aside for the new Centre for Disease Control, we don’t yet know what form that body will take, or what its priorities will be.

We still lack a replacement for the national prevention funding deal that was abolished more than a decade ago, and Australia is still spending far less than most other wealthy countries on keeping people healthy.

The Government has set the stage for reform in these and other areas.

The reviews of primary care have set out an ambitious agenda. So has the review of the National Health Reform Agreement, which called for new sections on rural health and First Nations health, among other things.

The 2023 National Health and Climate Strategy was a long-overdue response to a major threat to our health.

And a new way of funding the Aboriginal-controlled sector has been developed with the peak body representing the sector.

But, in line with the Government’s broader pre-election strategy, this Budget hasn’t done much to push these reforms forward.

Instead, it has focused on the simpler, immediate, and voter-friendly goal of cutting costs for patients.

In the meantime, the ‘cost-of-leaving’ the system unchanged continues to mount.

Preventable chronic disease will continue to grow, some communities will continue to miss out on essential care, and hospitals will continue to run less productively than they could.

The next Government – Labor or Coalition – must invest to build a strong system for chronic disease prevention, change how GP clinics are funded and staffed, fill gaps in access to care, and make hospitals more productive.

Otherwise, the Budget’s cost relief won’t last. In the long run, the costs from increased illness and more hospital visits will hit hip pockets – and government budgets – harder than ever.