I’m delighted to be here on the lands of the Ngunnawal people, and I would like to thank Philanthropy Australia for the opportunity to speak to you today.

This is a very exciting time for philanthropy in Australia. It was wonderful this morning to hear my future Productivity Commission colleagues, and parliamentarians, including Minister Andrew Leigh, talking about the vision to double giving by 2030.

It is rare in politics to see such concrete targets being set, and no doubt the risks to government of doing so and falling short are real. But setting goals and running at them is ultimately how transformative policy change gets delivered.

Delivering such ambitious growth in the sector will require new and innovative ways of working. Finding new ways to get philanthropy and government working together is a vital aspect of that innovation.

In his essay in The Monthly written over the summer holidays – a tradition among Australian politicians I have to admit I cannot relate to! – the Treasurer Jim Chalmers talked about opportunities for coordination and co-investment between government, business and philanthropy, noting that the objectives of these groups are increasingly aligned and intertwined.[1]

And while I am sceptical that cooperation can be a ‘cure all’ for future challenges – or a magic bullet for relieving government budget pressures – the opportunities are real, as we’ve just heard from Senator Rishworth, Matthew and Bernadette.

There is no doubt that the co-investment can work and have powerful impacts – I know that from my own experience working at the Grattan Institute. In fact, I would argue that the establishment of the Grattan Institute, 15 years ago this year, is a great example of how government, business and philanthropy can combine to deliver excellent outcomes.

For those of you not familiar with Grattan’s work, we are an independent, non-partisan public policy think tank. We research and advocate for policy changes to improve the lives of Australians.

Grattan began with a vision. Victorian Premier Steve Bracks and his Departmental Secretary Terry Moran had an idea for an influential independent policy think tank for Australia in the mode of Brookings Institution in the United States and the Institute for Research on Public Policy in Canada.

From the start, it was clear that such a concept would need government backing. It was also clear that the vision of a well-resourced, independent think tank would be much more powerful if the university and business sectors could also be persuaded it was an idea worth investing in.

Terry persuaded McKinsey’s Managing partner, Adam Lewis, to prepare a comprehensive plan to open the conversation with potential supporters.

It proved an attractive concept to a wide range of different stakeholders. Discussions around Commonwealth funding began with the Coalition government. Peter Costello initially supported the idea, but eventually it was Finance Minister Lindsay Tanner and Treasurer Wayne Swan who, after arriving in office, agreed to match the financial contribution from the Bracks government in Victoria.

The two government contributions were provided as a one-off endowment, in recognition of the need to preserve the Institute’s independence and its ability to make the case for difficult policy changes that may or may not align with the political interests of the government of the day.

Then Melbourne University came on board and provided a ‘home’ for Grattan – the converted warehouse down a cobbled lane off Grattan Street where we still reside to this day.

And two major Australian corporates, BHP and NAB, also backed the idea, becoming foundational supporters.[2]

Allan Myers was invited to chair and assemble the original Board. And my predecessor John Daley was appointed as the inaugural CEO.

Interestingly a similar model - providing anchor funding and a clarity of purpose, building stakeholder buy in and appointing a credible Board and capable CEO - was used at the time by the Victorian government to create a number of important institutions including the Australia and New Zealand School of Government, Victorian Opera, the Melbourne Recital Centre and the Wheeler Centre.

Grattan’s endowment continues to support Grattan’s operations to this day. Increasingly, however, we have supplemented this income with invaluable contributions from a number of trusts and foundations that have embraced the idea of investing in high-quality and independent policy work. They include Susan McKinnon Foundation, Summer Foundation, Scanlon Foundation, Myer Foundation, Third Link Investments, Cuffe Family Foundation, Origin Energy Foundation, Trawalla Foundation, Australian Philanthropic Services, and Ecstra Foundation.

Firms such as Medibank Private, Wesfarmers, Westpac and professional and legal services including Allens, Maddocks, McKinsey, BCG, PEXA and Urbis provide support through our corporate affiliate program.

And then there are the generous individual donors who give everything from $5 to many thousands to show their support for Grattan’s work each year. For each and every supporter we are deeply grateful.

Steve and Terry’s ‘Australian Brookings’ is now, I believe, an integral part of the policy landscape in Australia.

I am hugely proud of the quality, rigour and impact of our research.

Last year, our team of 28 produced 15 reports, which were downloaded almost 41,000 times. We held more than 1,300 stakeholder meetings, including almost 200 with politicians and political offices. Our work was cited more than 150 times by politicians and government agencies.

We also channelled our resources into selling our message to the broader public. Our staff gave 239 speeches (my 7-year-old daughter tells people my job is ‘lecturing at people’), published more than 130 opinion pieces in major newspapers, and our work was mentioned more than 45,000 times in the media.

We emphasise public advocacy in our work for two reasons.

The first is that there is an inherent value in adding facts and context to the public debate. In a media landscape that is increasingly shouty and riddled with mis- and disinformation, expert, research-based commentary on topical issues – presented in a way that people can engage with – is extremely important to rational policy debate.

Second is that publicly making the case for specific policy changes helps to shift hearts and minds. Major policy change is hard and often involves difficult trade-offs. People are much more receptive to change when the case has been made, made and made again – the so-called ‘vomit principle’.

And that brings me to the ultimate measure of success.

Grattan has proved its capacity to positively influence public policy in a way that I think has exceeded even the most ambitious hopes of its founders.

While successful policy changes have many mothers, there are so many policy initiatives and changes that I can point to and say, hand on heart, that Grattan played a key role in galvanising action.

I’d like to briefly mention some recent examples of reforms that were achieved at least partly thanks to our research and – yes – our endless ‘lecturing at people’.

- I’ll begin with health. Earlier this year the federal government embarked on major and long‑overdue changes to the way we deliver primary health care services. Funding and practice changes will support GPs to lead multidisciplinary teams, providing better outcomes for the growing share of patients managing complex chronic disease and, crucially, keeping them out of hospitals. The Prime Minister described these as ‘generational’ changes to Medicare. And although the reforms do not go as far as we would like (a constant refrain for an organisation that pushes for transformative change) they pick up many of the recommendations put forward in our late-2022 report, A new Medicare: Strengthening general practice.[4]

- In education, the NSW and Victorian Governments have so far allocated about $2 billion to small-group tutoring over the past three years to help school students who are struggling with reading and maths, in line with recommendations of successive Grattan reports.[5]

- The NSW Government is also procuring high-quality shared curriculum materials for schools and piloting new approaches to using administrative staff in schools. The announcement of this initiative cited our 2022 report, Making time for great teaching which is about freeing up teacher time to focus on the core teaching work that delivers better educational outcomes for our children.[6]

- In housing, the federal government has adopted a version of our 2021 proposal for a national Social Housing Future Fund [7]. The $10 billion fund will deliver 30,000 new social and affordable rental homes in its first five years, marking the Commonwealth’s biggest commitment to new social housing in more than a decade.

- In climate, the federal government has strengthened the so-called Safeguard Mechanism to reduce industrial emissions, in keeping with our recommendations on how Australia can get on the path to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.[8]

- The Victorian government has announced it will end new residential gas connections from January next year, a crucial step if we are going to have any chance of moving to net zero on home energy emissions.[9]

- I was personally delighted when the federal government delivered major reductions in out-of-pocket childcare costs, and movement towards 26 weeks of government paid parental leave, including time set aside for dads and partners. Both changes improve choice for families and will catalyse the social and economic benefits associated with higher women’s workforce participation. These are issues we have researched and advocated for at Grattan over the past three years [10]

- The government is also making changes to the skilled migration intake to reorientate to focus on migrants most likely to thrive in Australia – crucial for ensuring that Australia maximises the economic benefits from our migration intake. Again, this follows the approach that Grattan has advocated based on its detailed research on the migration system over the past two years.[11]

This is just a subset of the policy changes Grattan has had a hand in. Policy enthusiasts can find a more comprehensive list at our website.[12]

The upshot is: I would like to think the Australian and Victorian governments (and indeed all the states) have seen a lot of value for their respective $15 million investments 15 years ago.

I believe they have. The regular feedback I receive from public servants and politicians across the political spectrum on the value of Grattan’s research to their policy thinking and deliberations has further convinced me of this view.

If I was going to be cheeky, I might draw a comparison between the $15 million put into Grattan by the Commonwealth government – which has generated 15 years of high‑quality research and advocacy, with much more to come – and the almost $900 million spent on consulting services in a single year.13 I would argue that we look like very good value indeed.

And to our philanthropic supporters in all their stripes – Melbourne University, philanthropic funds, business and individual donors – I would like to say that your investment in Grattan has delivered at multiples that would turn Warren Buffett green with envy.

The policies we have influenced represent a mixture of new spending, more effective delivery and ‘growing the pie’. But even if we just take the spending on much needed programs in schooling, early learning and care, and social housing that Grattan has helped make a reality, our annual budget of about $5 million a year has translated into billions each year in well‑targeted spending across federal and state governments. Which brings me to an important point I want to make about how we think about impact in philanthropy. Despite the impact Grattan’s work has had over the past 15 years, it’s not easy finding philanthropic support for policy research and advocacy work in Australia.

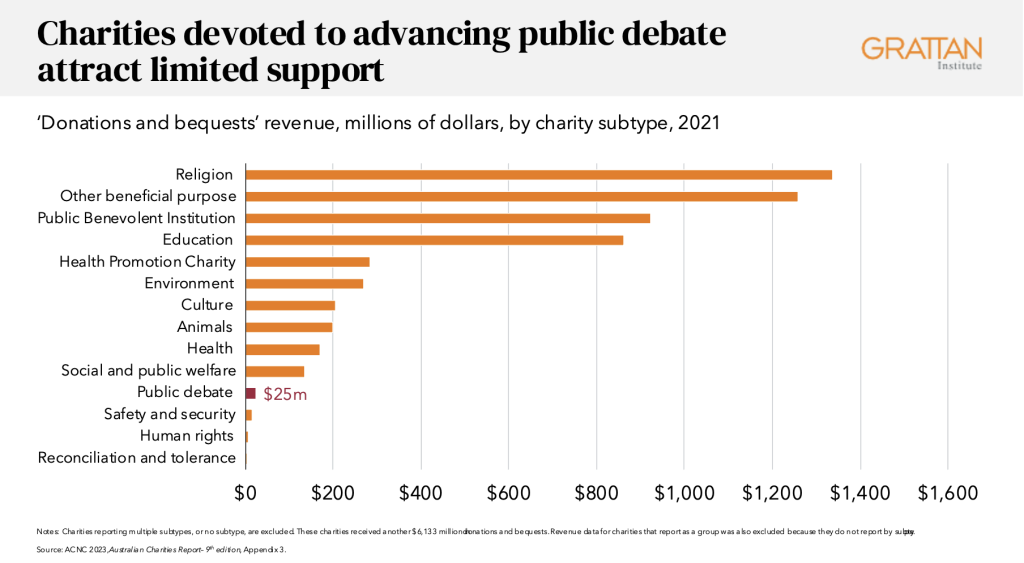

Indeed, compared to countries like the US, Australian philanthropists tend to be reluctant to put their philanthropic dollars into policy research and advocacy.[14] Donations and bequests to support the public debate are a tiny fraction of total Australian donations.

Of course, there are reasons why philanthropists might hesitate to dip a toe into the policy waters.

Investing in policy research and advocacy requires a way of thinking about success and failure that is very different from traditional philanthropic interventions such as direct service delivery.

It is more uncertain, much less linear and – because it is about politics – even great ideas don’t always get taken up. This means that policy-oriented philanthropists need to develop a stomach for failure and seeming ‘waste’.[15]

Similarly, advocacy is not for the faint hearted. Public policy is a contact sport. When billions of dollars are at stake, there can be plenty of eye-gouging. The people doing the research and advocacy usually take most of the heat – which can be helpful for the philanthropists supporting them. But ultimately, there may be times when unhappy vested interests will try to buttonhole trustees. Nonetheless, philanthropy is inherently independent. It should be able to stand the heat.[17]

Investment in positive policy change can take different forms, as we have heard today. But whether we’re talking about new and innovative interventions supercharged with government support, as in the Investment Dialogue; or collaboration to drive better government service delivery as envisaged by SEED, or organisations like Grattan that provide the evidence base and advocacy to make better policy a reality, it’s supporting these types of interventions that will generate macro change.

For philanthropists, policy-oriented giving can play an important role in a ‘portfolio’ approach – that is, an approach which aims to supercharge the impact of more typical philanthropic interventions by including higher-risk investments in policy change that can – and often do – pay enormous dividends by shifting the very levers of government.[18]

I think Grattan’s success – impossible without the governments and philanthropic backers who have allowed us to ‘do what we do’ – are a testament to how this approach can pay off.

In three weeks’ time, I will leave my role as Grattan Institute CEO, and I will do so with immense pride in an organisation that has punched above its weight in improving the lives of Australians.

I truly hope the philanthropic sector realises its vision of doubling giving; and I hope that it continues to grow in sophistication and in its willingness to take some of these harder bets in policy-oriented philanthropy.

Most of all, I look forward to seeing the myriad ways in which philanthropy and governments will work together in the coming years to change the lives of Australians for the better.

Footnotes

- Chalmers, J. (2023). “Capitalism after the crises”. The Monthly. February 2023.

- For more on the history of the Grattan Institute see: Davis, G. (2018). A history of the Institute.Grattan Institute; Grattan Institute (2019). Grattan Institute: The first 10 years.

- In 2021-22, the Grattan Institute had operating expenditure of $4.9 million: Grattan Institute (2022). Grattan Institute Annual Report 2021-22. In the same year, the Brookings Institution reported operating expenses of $86.4 million: Brookings Institution (2022). Brookings Institution Annual Report 2022. As at July 1 2022, Brookings had 396 staff: Brookings Institution (2022). Inclusion and diversity.

- Breadon, P. and Romanes, D. (2022). A new Medicare: Strengthening general practice.Grattan Institute. The recommendations were picked up in the Federal Government’s Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report, which then informed the National Cabinet meeting decision in April 2023: Australian Government (2022). Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report; Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (2023, April 28). National Cabinet meeting outcomes: Strengthening Medicare.

- Sonnemann, J. and Goss, P. (2020). COVID catch-up: Helping disadvantaged students close the equity gap. Grattan Institute; Sonnemann, J. and Hunter, J. (2023). Tackling under-achievement: Why Australia should embed high-quality small-group tuition in schools. Grattan Institute.

- Hunter, J. and Sonnemann, J. (2022). Making time for great teaching: How better government policy can help. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. (2021). A place to call home: it’s time for a Social Housing Future Fund. Grattan Institute.

- Wood, T., Reeve, A., and Ha, J. (2021). Towards net zero: A practical plan for Australia’s governments. Grattan Institute.

- Wood, T., Reeve, A., and Suckling, E. (2023). Getting off gas: why, how, and who should pay? Grattan Institute.

- Wood, D. and Emslie, O. (2021). Dad days: How more gender-equal parental leave could improve the lives of Australian families. Grattan Institute; Wood, D., Griffiths, K. and Emslie, O. (2020). Cheaper childcare: A practical plan to boost female workforce participation. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B., Wiltshire, T. and Reysenbach, T. (2022). Australia’s migration opportunity: how rethinking skilled migration can solve some of our biggest problems. Grattan Institute.

- Grattan Institute (2023), Grattan’s impact.

- The federal government spent $888 million in consulting services in 2021-22: Australian National Audit Office (2023). Australian Government Procurement Contract Reporting – 2022 Update. Auditor‑General Report No. 11 of 2022-23.

- Large and sophisticated US foundations are heavily engaged in policy philanthropy. One study estimated that more than half of major US-based philanthropists have ‘serious policy interests and ambitions’: Goss, K. (2016). “Policy plutocrats: How America’s wealthy seek to influence governance”. PS: Political Science & Politics 49.3, pp. 442-448.

- Teles, S. and Schmitt, M. (2011). “The Elusive Craft of Evaluating Advocacy”. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Summer 2011.

- Daley, J. (2017). What philanthropy, advocacy, and policy influencers can learn from political economy. Grattan Institute.

- Goss (2016), see n. 14.

- Karnofsky, H. (2016). “Hits-based Giving”. Open Philanthropy; Teles and Schmitt (2011), see n. 15.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO