The Commonwealth could save A$1.3 billion each year by reforming the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), according to a report released today by the Grattan Institute. The report, Australia’s bad drug deal, shows that if the PBS simply paid prices for drugs that many Australian public hospitals or New Zealand’s national pharmaceuticals purchaser pay, the government could be on its way to a budget surplus.

If Australia also encouraged doctors and patients to replace some drugs with others that achieve a similar result, at least another A$550 million could be saved every year

These are savings too good to miss. So why has Australia missed them?

The Grattan report compares spending on the 73 top drug-dosage combinations which are prescribed most often or that we spend most on. These 73 drugs account for almost half of PBS spending.

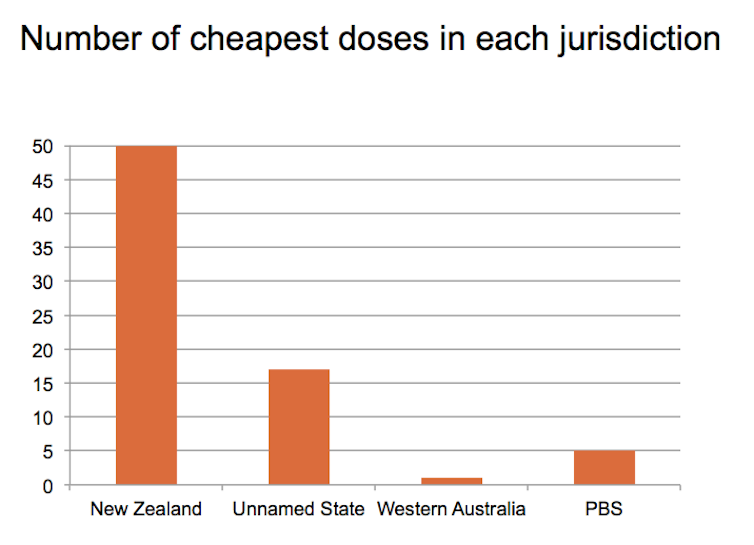

We looked at prices negotiated by New Zealand’s purchaser, by Western Australia’s public hospitals and by public hospitals in an anonymous state. The difference from PBS pricing is dramatic. Of the 73 drugs we looked at, the PBS got the best deal for only five.

Most of the savings that New Zealand and Australian public hospitals have made come from off-patent drugs, known as generics. These provide an equivalent therapeutic effect to the branded product.

The marginal cost of manufacturing off-patent drugs is very low, so there can be big battles over market share and big profits to be made. This provides the PBS with a golden opportunity to save money in negotiations with drug companies, but the opportunity is being missed.

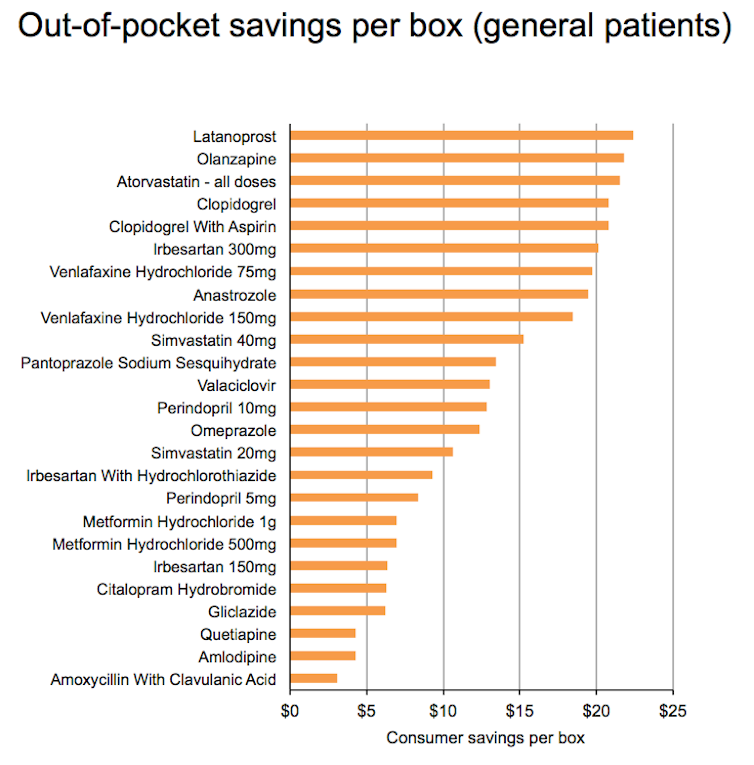

Take atorvastatin, a cholesterol-lowering drug that is one of the most commonly prescribed medicines on the PBS. The PBS pays manufacturers A$51.59 for each 30-pill packet of the 40 milligram version of this drug. New Zealand, by contrast, pays a mere A$1.94 for the same number of pills for a generic version of atorvastatin. Western Australian public hospitals pay A$4.44.

If the PBS paid the same as New Zealand across all doses of atorvastatin, it would save A$1.4 million every day. If Perth users of atorvastatin (who are not on concession cards and are below the safety net) could buy the drug at a retail pharmacy at the same price the public hospital down the road pays, they would save A$19 every time they purchased a 30-pill pack, even after retail markups.

It’s a ridiculous situation, and there are many reasons we got to it. First, the politics of listing new drugs is topsy-turvy. For a time, every new drug listed had to be approved by Cabinet, a process a Senate committee described as “wasteful” and “duplicating an existing process, albeit without the appropriate qualifications or information available to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee”.

Now the Cabinet only decides on drugs with a total cost of more than A$10 million, but even this involvement is subject to the same criticisms previously levelled by the Senate committee. Of course, allocation of public funds involves political decisions, but the politics should be at the beginning of the process, in determining what the total budget will be, not at the end, in second-guessing experts.

The whole framework for negotiating prices is part of a political accommodation. The main pricing body, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Pricing Authority, is a representative body. It has two members out of six nominated by the pharmaceutical industry, which gives vested interests too much power.

The government has signed a deal with the main pharmaceutical manufacturing lobby group, Medicines Australia, which gives them a rent-free holiday for five years, with the government promising not to make any changes to pharmaceutical pricing in that period other than those announced and signed off at the start. Luckily, the agreement expires next year, and there is an opportunity for reform. What should it be?

A three-step plan for reform

Our report proposes a three-step plan to set PBS pricing on the right track.

The first step is getting the framework right. We need to reverse the politics. Politicians should be involved at the start of the process, not at the end. Parliament should set the budget for drugs and then get out of the way of sensible decisions about what drugs should be listed on the PBS and at what price.

Australia needs something like the process New Zealand has adopted, in which an indexed budget determined by government sets the context, but then an independent expert board makes the priority choices (with public consultation) and negotiates prices.

The second step is to follow other countries and expect big price reductions when drugs come off-patent. At present, the PBS cuts manufacturers’ prices by 16%, but this figure is far too small compared with reductions achieved in other countries. To get to best practice quicker, prices of new generics should be at least halved immediately and then benchmarked internationally.

After these changes have been bedded down, the new expert board should encourage more cost-effective drug use by focusing on sensible substitutions within classes of similar drugs.

As our health budget continues to rise, it’s time for Australia to get tougher in negotiations with international drug companies. There is no reason the Australian taxpayer should pay such high prices when taxpayers in other countries do not.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.