People with profound disability face unique challenges in housing. Financial, social, and administrative barriers abound. Australia’s disability insurance program, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, is failing many of these people.

The NDIS is responsible for housing and living support for people with the most severe disability, making this one of the few groups of people for which the Commonwealth, as opposed to the states and territories, is responsible for housing services.

The NDIS plays a critical role in housing people with profound disability, who may need substantial housing support because their primary carers (often parents) are no longer able to house and support them. People with profound or severe disability tend to be in low- income households and have low labour force participation rates (about 27 per cent) and high unemployment rates (about 12 per cent).1

Disability also comes with its own distinct costs for housing. People with disability may need modifications to their homes, which can be expensive and is often difficult if they rent. Most salient to the NDIS, though, is that people with profound disability who want to live independently may need intensive living support.

The costs of around-the-clock living support are so high that hardly any Australians could afford them. Such costs are, of course, one of the main justifications for the NDIS – to pool the unlikely, but incredibly costly, risk of lifelong and severe disability. And while the costs of lifelong and severe disability justified the existence of the NDIS, they are now threatening the sustainability of that very scheme.

Grattan Institute’s recent report, Better, safer, more sustainable: How to reform NDIS housing and support, explains how to ensure the NDIS can safely and sustainably provide housing and living support for people with profound disability.

High and rising costs for the NDIS

Grattan Institute research shows that more than 43,500 Australians with profound disability in the NDIS have support packages that cost more than $350,000 per person, per year, on average.

Group homes are often the only option for people with severe disability. People in group homes tend to have little say in where they live, who they live with, and who provides their support. Worse, evidence from the Disability Royal Commission and the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (the Scheme regulator) found that there are high rates of violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation in group homes.

It’s a wicked problem: Australia spends in the realm of $15 billion on housing and living support in the NDIS, and yet quality, safety, and choice can be wanting. For this price tag, people with disability deserve – and taxpayers expect – quality housing and living supports.

Pockets of innovation show promise for the future of the NDIS

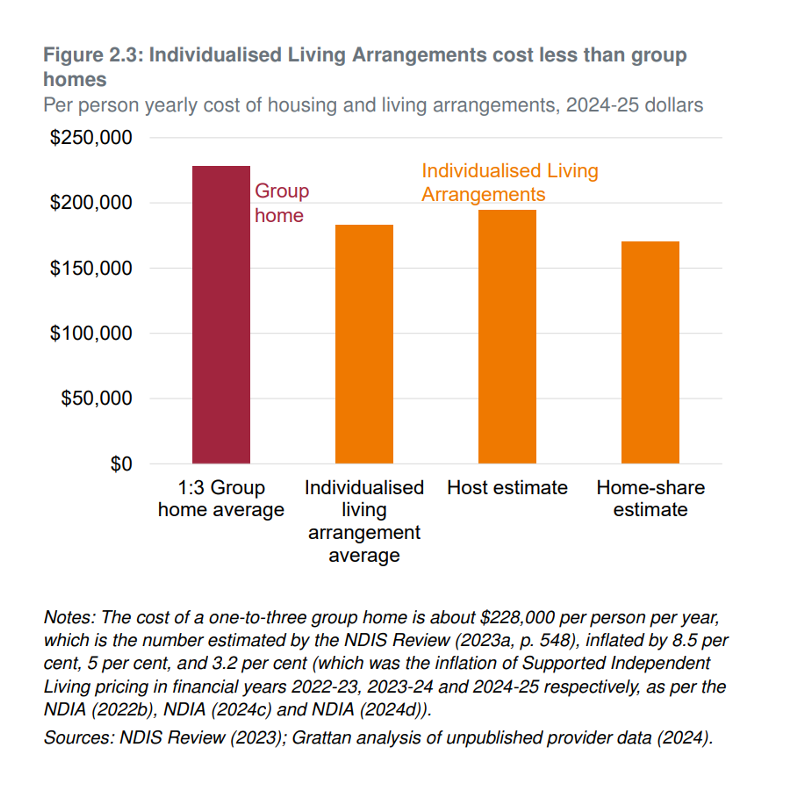

There are better alternatives to group homes: Grattan Institute research shows that it is possible for people who need intensive support to live in ordinary homes in the community for a price that is the same as or less than a group home. And with options about where and with whom they live, people with disability have genuine choice about their home lives and are more likely to find a better fit for their individual circumstances.

Individualised Living Arrangements draw on a mix of supports, including formal (paid-by-the-hour support workers), semi-formal (hosts or flatmates who receive a subsidy for their expenses), and informal supports (family and friends).

For example, a host arrangement is where an adult with disability in the NDIS lives with a “host family” or “host flatmate”, who is not related to them, in the host’s home, becoming part of the household. The host could be a couple or an individual, they provide semi-formal support while going about their everyday activities, and they receive a subsidy for what they do.

A similar example is a home-share arrangement, where an adult with disability in the NDIS lives in their own home (owned or rented) with a flatmate who provides semi-formal support.

Semi-formal support from hosts and flatmates can include emotional support, companionship, cooking, cleaning, overnight help, and other household tasks.

Such arrangements have been working well in the United Kingdom, British Columbia, and Western Australia. In the UK, host arrangements are regularly ranked as some of the best-quality housing and living supports for people with disability, while in British Columbia, host and home-share arrangements now outnumber group homes as the most common kind of support.

Grattan Institute estimates indicate that Individualised Living Arrangements can be cheaper than group homes for three residents with disability and one around-the-clock support worker (also known as a one-to-three ratio).

From group homes to share houses

Governments tend to like group homes because residents with disability share a support worker, rather than living alone with one support worker each. This economy of scale from shared living is a good and necessary feature for households that only draw on formal, paid-by-the-hour support workers.

However, group homes have come to be characterised by their institutional features – a lack of choice for people over their home lives, their flatmates, their support workers, and the rhythms of their days.

There is nothing wrong with people with disability wanting to live together; those who want to live together and share supports should be able to. In our report Better, safer, more sustainable, Grattan Institute recommends system changes to enable the transition from group homes to share houses, which are run as homes, not service facilities. Combining the economy of scale from sharing support, with genuine choice at home, is a cost-effective way to ensure housing and support for people with disability now and into the future.

How the NDIA can ensure better housing and living supports

Paying the rent is a struggle for people with no or low income, which includes the vast majority of people with profound disability. People in the NDIS contribute 100 per cent of their Commonwealth Rent Assistance, plus up to 50 per cent of their Disability Support Pension, to cover rent in group homes or other accommodation.

Grattan Institute has long called for an increase of at least 40 per cent to Commonwealth Rent Assistance. And yet, for people with profound disability who need housing and living support in the NDIS, renting in the private rental market is a challenging prospect, financially and socially. We recommend a rental payment to help people move out of their group homes and into the private rental market in their local community, near networks of family and friends.

Right now, people with disability are given line-item budgets that lock them into options before they’ve had a chance to try them out. Grattan Institute proposes that people with disability get a flexible budget up front, and then start the planning process.

We all need information, advice, and the chance to try things out so we can plan our housing. Likewise, independent advice is crucial for people with disability to plan their housing and support within their budget. Many people with disability need extra help to avoid being exploited, and to make decisions. For many, it will be their first attempt at living out of the family home. Grattan Institute recommends that the NDIA commission ‘housing and living navigators’, to plan supports shoulder-to-shoulder with disabled people who need 24/7 assistance.

Our research shows genuine choice and higher-quality services are possible for Australians with disability – and governments don’t have to spend buckets more to get it done.

Footnotes

- ABS, Survey of Disability, Ageing, and Carers (2022). Note that we use ‘profound or severe disability’ to align with the ABS categories of ‘profound core activity limitation’ or ‘severe core activity limitation’.