Published at The Conversation, Thursday 2 August

Out-of-pocket costs is a hot-button issue. It is on the agenda for a health ministers’ meeting this week, where the Victorian health minister will push the Commonwealth for more transparency about doctors’ fees.

The Medical Board of Australia is also finalising consultations on its draft Code of Conduct for doctors this week, which also emphasises that fees should be transparent.

Of course fees should be transparent, but that’s not good enough. Doctors, and especially specialists, should also be required to set fees that are “fair and reasonable”.

From January to March, only 30.8% of visits to specialists were bulk-billed, and the average out-of-pocket costs for those not bulk-billed was A$87.62 for each visit.

The visit to the specialist may lead to further costs such as diagnostic imaging (such as X-rays, ultrasounds and MRI scans), where 78.2% of services are bulk-billed and the average out-of-pocket is A$104.56. The alternative to these high charges is referral to a public hospital outpatient clinic, but the wait between a referral and an appointment can be very long indeed.

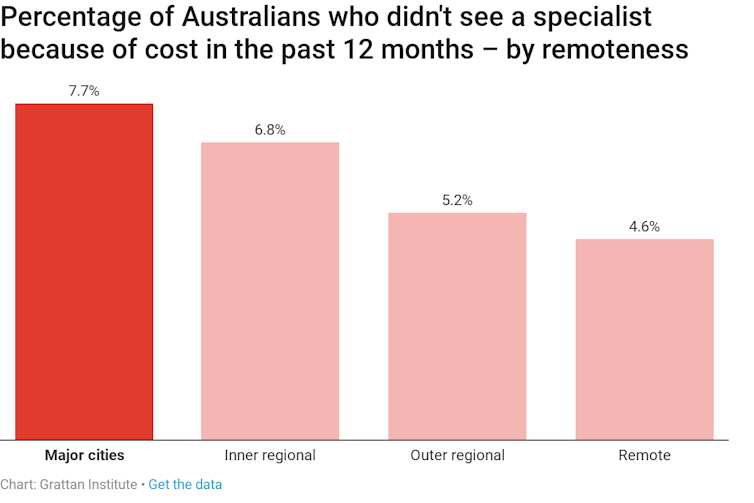

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that in 2016-17 about 815,000 people missed out on seeing a specialist because of cost. That amounts to one out of every 14 people who needed to see a specialist.

Unlike other aspects of health disadvantage, people in metropolitan areas report higher rates of skipping specialist consultation:

What are doctors’ ethical obligations when it comes to fee-charging? The draft Code says doctors should:

- ensure that your patients are informed about your fees and charges

- be transparent in financial and commercial matters.

But, as I argue in a Grattan Institute submission to the Medical Board, this is too weak. The medical profession in Australia is out of step with consumer expectations, and with practices in other professions.

The legal profession, for example, has a statutory obligation to charge “costs that are no more than fair and reasonable in all the circumstances”. The Legal Profession Uniform Law in NSW also sets out factors which may affect fees, such as “the quality of the work done” and the “level of skill, experience, specialisation and seniority” of the lawyers involved.

Fees charged by medical practitioners, especially specialists, have recently been the subject of media criticism, notably by medical journalist Dr Norman Swan on ABC TV’s Four Corners. So they should be.

Academic studies have also shown that specialist fees – especially surgeons’ fees – vary wildly.

Policy responses have been based on the assumption that the problem is confined to a small number of specialists charging egregious fees.

If this were the case, it could be argued that these doctors were operating outside professional norms. But the evidence shows it’s not unusual for fees to be significantly in excess of even the Australian Medical Association (AMA) rate. The AMA rate is significantly above the Medicare rebate but is often regarded by medical practitioners as the appropriate fee to charge.

This can be an acute problem for some of the most vulnerable Australians: patients with several chronic diseases – such as diabetes, heart disease and depression – who are excessively billed by each of their medical practitioners several times a year.

Under the draft Code of Conduct, these doctors could not be seen as acting unprofessionally if they had simply informed their patients of the proposed fees.

Doctors, especially specialists, have a lot of power in these circumstances. Patients are often reluctant to shop around for a different specialist, if they have been referred to a specific specialist and have initiated contact with that specialist.

An obligation to be transparent is a necessary but not sufficient ethical obligation for contemporary medical practice. The draft Code says doctors should:

‘not exploit patients’ vulnerability or lack of medical knowledge when providing or recommending treatment or services’

But an obligation to not exploit patients’ vulnerability is not enough. The Code should be expanded to include a specific obligation on doctors to set fair fees.

This is not to dismiss the transparency obligation as irrelevant. Rather, the Code needs to supplement an obligation to disclose fees (transparency) with an obligation not to exploit patients financially.

Better transparency provisions

The existing transparency obligation should also be tightened. Too often, patients do not learn of the proposed fees until their initial visit to a specialist.

Patients may be able to discover the out-of-pocket costs associated with the initial consultation when making the booking, but probably not the out-of-pockets for any procedures which might be recommended. By then, the patient may not be able to assess properly whether they want to continue with this specialist.

And in some situations – particularly with anaesthetists – the fee discussion can take place at the time of an operation or procedure, leaving the patient with no effective choice at all.

It is therefore important that the transparency of fees is timely. Indicative fees for procedures could be revealed on specialists’ websites, for example, so that patients (and their general practitioners) could make informed decisions before committing to their first consultation.

The Medical Board should tighten its Code of Conduct for doctors. If it doesn’t, too many Australian patients will continue to pay unfair, even exorbitant, fees.

![]()