Failure to invest in prevention increases health inequality

by Peter Breadon

We tend to ignore unfair gaps in sickness and health between different groups in Australia. But if you take a moment to think about them, they’re shocking. Men and women who live in poorer areas can expect to die six and four years earlier than those who live in wealthy areas. Even though they die younger, on average they spend more time living with illness and disability.

Compared to people who live near the start of the T1 Western Line – Central station – in Sydney, people in Parramatta, half an hour down the line, die slightly earlier on average. And by the time you reach Mount Druitt, locals lose a staggering one-and-a-half times the years of life on average, compared to people back at the start of the line.

Many things cause these disparities. Less access to healthcare plays a part, but exposure to health risks plays a much bigger role.

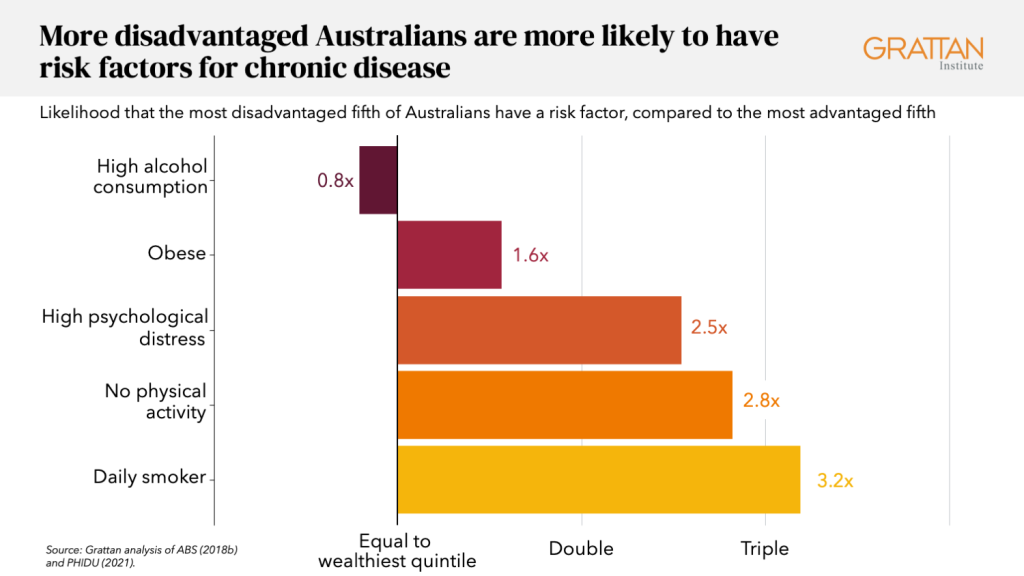

People living in outer regional and remote areas are more likely than people in the cities to drink sugar-sweetened drinks daily. Aboriginal people are exposed to more health risks than other Australians. And compared to the most advantaged fifth of Australians, the most disadvantaged fifth are more than three times as likely to be daily smokers.

Failure to invest

All this means that fairer health outcomes won’t happen without a level playing field on the causes of illness. There are proven ways to reduce those risks to our health, but Australia is doing less than many other countries to tackle them.

As a share of health spending, Australia invests far less in preventing illness than most other wealthy countries, and just a fraction of what the UK and Canada spend.

And when it comes to setting rules to make foods healthier, Australia also lags far behind leading countries.

Dozens of countries have rules to reduce the use of toxic trans fats, which cause heart disease, and 85 countries have a tax on sugar-sweetened drinks. Australia hasn’t introduced either measure.

Salt is another example, as a new Grattan Institute report shows.

The typical Australian eats almost twice the maximum recommended amount of salt, resulting in about 2,500 deaths each year from conditions such as high blood pressure and heart disease.

Most of the salt we eat is in manufactured foods. That’s why many countries – including Australia – set limits on the amount of salt in different types of food, such as bread or biscuits.

But Australia’s limits are voluntary, set in consultation with the food industry, apply to only a limited range of foods, and have a loophole that allows manufactures to exclude products.

On top of all that, the targets are so weak that most products already met them when the targets were set. It’s no wonder they have done almost nothing to reduce population salt intake.

Regulation matters

Australia should set mandatory salt limits at levels the UK has already reached.

Over the next 20 years this would add 36,000 healthy years of life, and save hundreds of lives each year. Without policies like this the cards stacked against us, with most Australians now living with a chronic disease. And the game is totally rigged for many disadvantaged Australians.

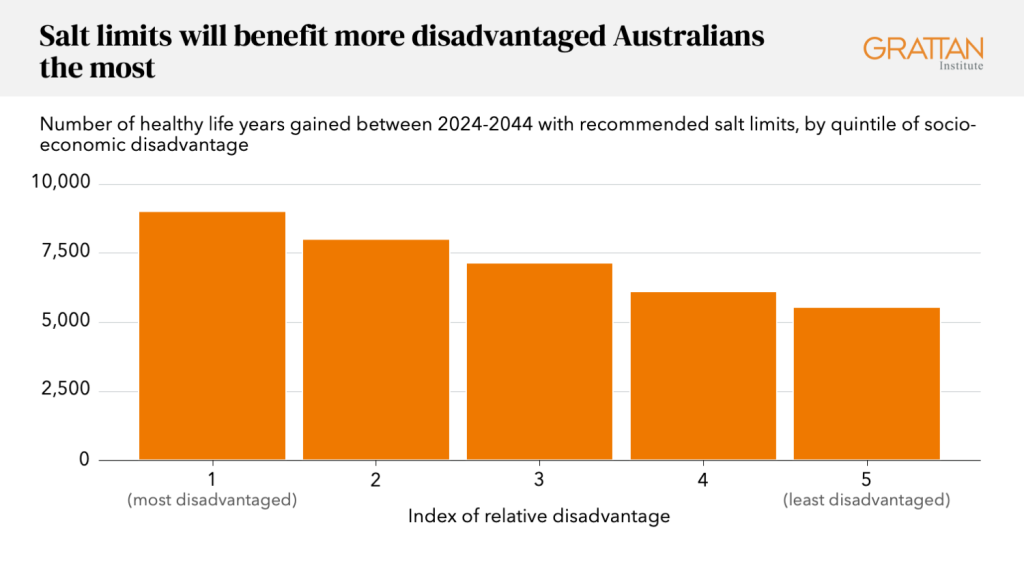

Modelling from the University of Melbourne’s SHINE program shows the difference that better policy would make.

Our recommended salt policy would give every Australian, on average, more years of healthy life.

But the poorest Australians would get 63 percent more gains than the wealthiest – so the health gaps in Australia would start to narrow.

Government action needed

It’s the same story for many types of prevention policies: they benefit most people, but they benefit disadvantaged people the most.

It will take government action to achieve these gains, because individuals can’t solve this problem on their own. Relying on individuals to fight an environment that pushes us towards unhealthy options has failed again and again. And that fight is much harder for people who suffer disadvantage.

There is no evidence that poorer people care less about their health or have less willpower. But there is lots of evidence to show that they often face bigger barriers to choosing healthy options. For example, more disadvantaged Australians have fewer healthy options that they can afford, and are likely to be exposed to more advertising for unhealthy options.

Inequity and structural disadvantage have consistently been identified as the cause of higher levels of illness among poorer people, not the preferences of those living in disadvantage.

No society has eradicated gaps in health between rich and poor, and we probably never will.

But while they are no substitute for reducing disadvantage, there is ample evidence that common-sense prevention policies can at least start to shift the dial, making health outcomes fairer.

Stronger food policies can reduce government expenditure, make people healthier, and make society fairer.

That leaves the onus on people who reject change – typically the leaders of industries with a vested interest – to explain why governments shouldn’t get serious about making healthy choices easier.

Peter Breadon

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO