Published at The Conversation, Tuesday 10 September 2013

The dictionary has many words that could describe health policy in the 2013 federal election campaign – anodyne, soporific and vapid all come to mind.

Australia’s health policy problems cannot afford the same vacuity from the next government so here’s hoping the campaign wasn’t a sign of things to come.

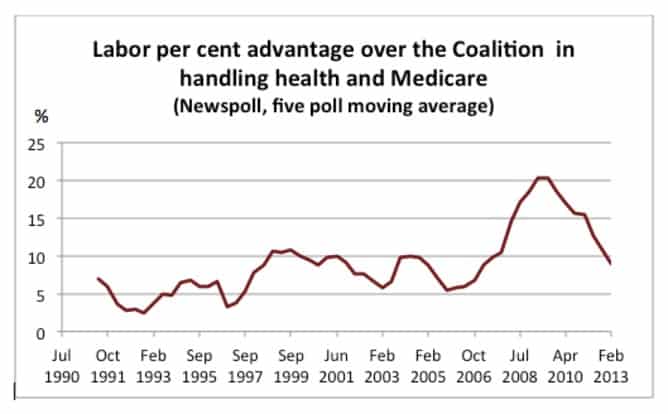

Health policy is traditionally a Labor strength and so it’s easy to understand why the Coalition was keen to avoid any attention to the area. Every day there was a discussion about health was a day the Coalition was on the back foot.

No counter for ‘small target’

The Coalition’s “small target” strategy had few commitments, a net cost of only A$344 million over the next four years (the forward estimates’ period), and no apparent nasty surprises.

What’s puzzling is that the Labor Party didn’t advance visionary policies to garner public attention and focus the debate.

Sure, Kevin Rudd and Tanya Plibersek tried to raise fears about cuts to “frontline services”. Initially, shadow minister Peter Dutton had claimed that Medicare Locals (a Labor creation designed to provide a platform for primary-care services to support general practice, such as physiotherapy and other allied health services, and local planning) would be “reviewed”.

But Opposition leader Tony Abbott and Dutton subsequently backpedalled furiously on comments that gave rise to concerns about their abolition.

Labor has experience with bold health policies. In the 1970s, the party fought bitter elections to introduce Medibank.

More recently, both Mark Latham’s 2004 Medicare Gold and then-opposition leader Kevin Rudd’s 2007 promise to “call a referendum for the Commonwealth to take over the running of hospitals if necessary” were received positively by voters.

Why the reticence?

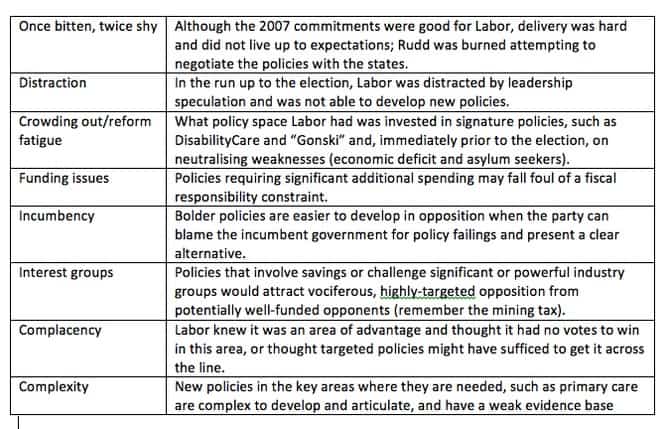

A number of hypotheses – listed in the table below – might explain Labor’s policy gap.

Only insiders can know the reason or the combination of these reasons (and any others not listed) that accounted for the strategy Labor pursued.

In the dying hours of the campaign, Labor trumpeted its claim as the party of Medicare with a 30th birthday celebration/cake.

Health policy now needs to build on Medicare’s strengths to address contemporary problems better, especially how we strengthen our primary-care system’s ability to manage chronic disease and multi-morbidity (having many illnesses at once).

This isn’t going to be easy.

Tackling the big issues

The incoming government’s policy to expand research into dementia, hopefully including health and aged-care systems research, is a good idea but could have gone further.

Labor could have built on its Medicare Locals platform to signal primary-care system reform. Given the weak evidence base of what works in system reform in primary care, Labor could have started a system redesign effort, perhaps funding trials of new approaches to primary health-care funding and delivery.

This wouldn’t have broken the bank and could have even been electorally appealing, offering Medicare Locals the potential to be in a trial. It could have been funded by addressing waste in the health-care system (such as paying too much for pharmaceuticals).

The issue for the incoming government is that the need for primary-care reform won’t go away. Primary-care reform doesn’t have to involve Medicare Locals. They could be by-passed with policies based on changing financial incentives on general practitioners, such as blending fee-for-service and capitation payment models (these latter involve paying a medical practitioner a set amount for each patient over a period of time).

But Medicare Locals are the only “game in town” in terms of a primary-care platform. The incoming government will need to overcome its apparent ambivalence towards them to allow proper consideration of all policy options.

Voters have been rightly disappointed by the health “options” presented to them at this election. It’s unfortunate that what they regard as one of the most important election issues was buried in a blancmange of bipartisan blandness during the election campaign.