Published at The Conversation, Monday 5 March

So much of Australia’s history and success is built on immigration. Migrants have benefited incumbent Australians by raising incomes, increasing innovation, contributing to government budgets, smoothing over population ageing and diversifying our social fabric. But it is also true that immigration is affecting house prices and rents.

Australian governments are squandering the gains from migration with poor housing and infrastructure policies. Our new report, Housing affordability: re-imagining the Australian dream, shows what’s at stake. Unless the states reform their planning systems to allow more housing to be built, the Commonwealth should consider tapping the brakes on Australia’s migrant intake.

Immigration has increased housing demand

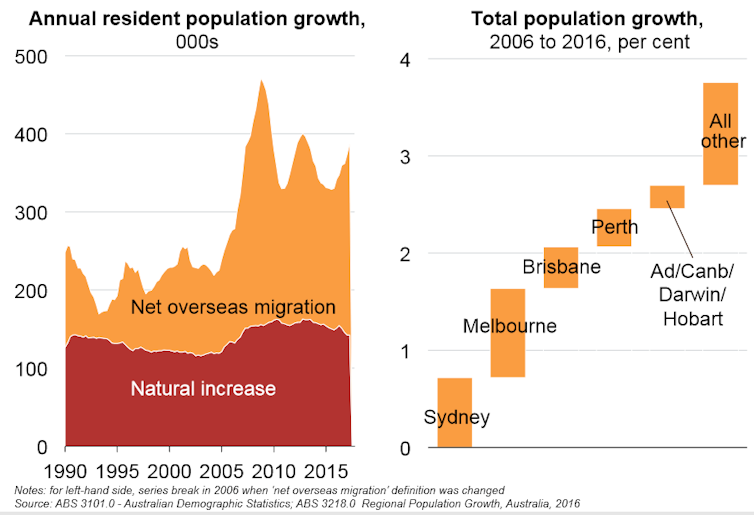

Australia’s migration policy is its de-facto population policy. The population is growing by about 350,000 a year. More than half of this is due to immigration.

Since 2005, net overseas migration – which includes the increase in temporary migrants – has averaged 200,000 people per year, up from 100,000 in the previous decade. It is predicted to be around 240,000 per year over the next few years.

Immigrants are more likely to move to Australia’s big cities than existing residents, which increases demand for scarce urban housing. In 2011, 86% of immigrants lived in major cities, compared to 65% of the Australian-born population.

Chart 1. Migration has jumped, and so have capital city populations

Not surprisingly, several studies have found that migration increases house prices, especially when there are constraints on building enough new homes.

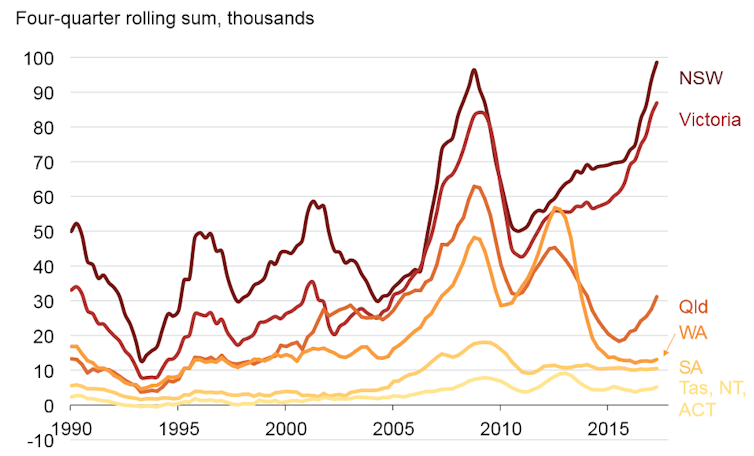

The pick-up in immigration coincides with Australia’s most recent housing price boom. Sydney and Melbourne are taking more migrants than ever. Australian house prices have increased 50% in the past five years, and by 70% in Sydney.

Chart 2: Net overseas migration into NSW and Victoria is at record levels

Of course immigration isn’t the only factor driving up house prices and rents. Housing also costs more because incomes rose, interest rates fell and banks made it easier to get a loan. But adding 2 million migrants in the past decade has clearly increased how many new homes are needed.

We haven’t built enough homes

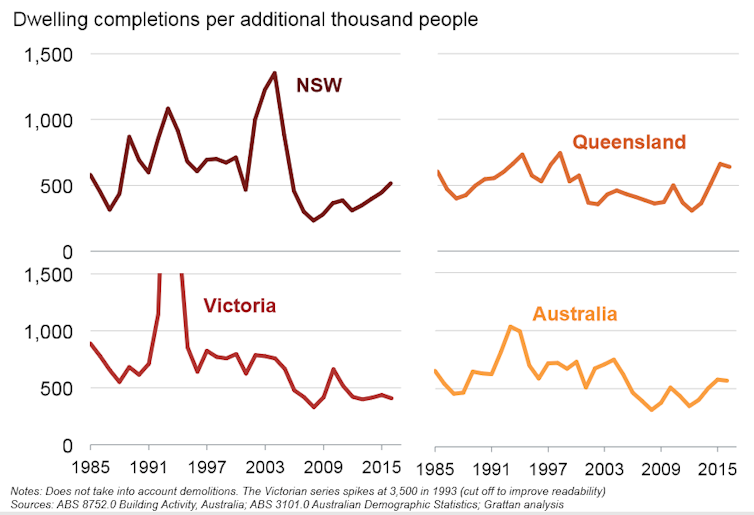

Housing demand from immigration shouldn’t lead to higher prices if enough dwellings are built quickly and at low cost. In post-war Australia, record rates of home building matched rapid population growth. House prices barely moved.

But over the last decade, home building did not keep pace with increases in demand, and prices rose. Through the 1990s, Australian cities built about 800 new homes for every extra 1,000 people. They built half as many over the past eight years.

We estimate somewhere between 450 and 550 new homes are needed for each 1,000 new residents, after accounting for demolitions. And because more families are breaking up and the population is ageing, more homes are needed to accommodate households with fewer members.

The imbalance between demand and supply has consequences. Younger and poorer households are paying more for housing, and owning a home depends more on who your parents are, a big change from the early 1980s.

Chart 3: Housing construction lagged population in the last decade, but has picked up

Only in the past couple of years has construction started to match population growth, especially in Sydney. It’s no coincidence that Sydney house prices have finally moderated in the past six months.

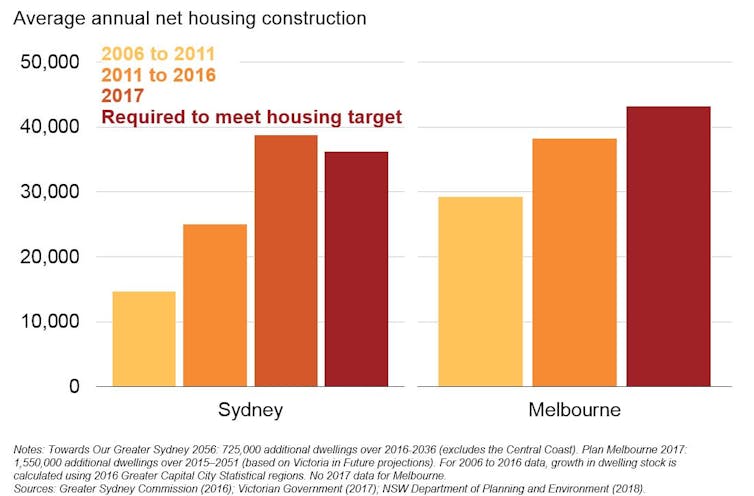

But the backlog of a decade of undersupply remains. Development at today’s record rates is the bare minimum needed to meet record population growth built into Sydney’s and Melbourne’s housing supply targets over the next 40 years.

Chart 4: Strong housing construction will need to be maintained to meet city plan housing targets

So what should governments do?

Building more housing will improve affordability the most – but slowly. Even at current record construction rates, new housing increases the stock of dwellings by only 2% each year. But building an extra 50,000 homes a year nationwide for a decade would lead to national house prices between 5% and 20% lower than otherwise. Do it for longer and prices will fall even further.

State governments need to fix planning rules to allow more housing to be built in inner and middle-ring suburbs. More small-scale urban infill projects should be allowed without council planning approval. And state governments should allow denser development “as of right” along key transport corridors. The Commonwealth can help with financial incentives for these reforms.

But the politics of planning in our major cities is fraught. Most people in established middle suburbs already own their houses. Prospective residents who don’t already live there can’t vote in council elections, and their interests are largely unrepresented.

If we want to maintain current migration levels, along with their economic, social and budgetary benefits, we need to do better at planning to allow more housing to be built.

What does this mean for the migrant intake?

The Australian government should develop a population policy, as the Productivity Commission recommended. It should articulate the appropriate level of migration given its economic, budgetary and social benefits and costs. This should include how it affects the Australian community living with the reality of land use planning policy – and contrasting this with the effect of optimal planning policy.

If planning and infrastructure policies don’t improve, the government should consider cutting the migration intake. This would reduce demand for housing, but would also reduce the incomes of existing residents.

The best policy is probably to continue with Australia’s demand-driven, relatively high-skill migration and to build enough homes for the growing population. But Australia is in a world of third-best policy: rapid migration and restricted housing supply are imposing big costs on people who don’t already own their homes. If the states are not going to reform planning rules to increase the number of homes built, then the Australian government should consider whether reducing migration is the lesser evil.

Any reduction should be modest and targeted at the parts of the migration program that provide the smallest benefit to Australian residents and migrants themselves. Balancing these interests is difficult, because each part of the program has different economic, social and budgetary costs and benefits.

Cutting back family reunion visas would have substantial social costs. Limiting skilled migration would hurt the economy and many businesses. Restricting growth in international students would reduce universities’ incomes.

There are also broader costs to cutting the migrant intake. It would hit the Commonwealth budget in the short term. Most migrants are of working age and pay full rates of personal income tax. And many temporary migrants, such as 457 visa holders, can’t draw on a range of government services and benefits, including welfare and Medicare. More importantly, cutting back on younger, skilled migrants is likely to hurt the budget and the economy in the long term.

But there is no point denying that housing affordability is worse because of a combination of rapid immigration and poor planning policy. Rather than tackling these issues, much of the debate has focused on policies that are unlikely to make a real difference. Unless governments own up to the real problems, and start explaining the policy changes that will make a real difference, Australia’s housing affordability woes are likely to get worse.

![]()

Published at

Published at