How to tackle burnout among healthcare workers

by Stephen Duckett, Edward Meehan

The COVID-induced ‘Great Resignation’ among healthcare workers could harm patients. Governments, hospitals, practice owners and other primary care employers should change the way they respond to burnout to better protect patient safety.

‘Burnout’ is a mental health condition caused by job stress. It leads to workers feeling exhausted, ineffective, and mentally separated from their job. It makes them more likely to work part-time or quit.

Multiple Australian studies have found burnout rates of more than 50 percent among healthcare workers, although rates are lower in general practice. US surveys have also consistently shown burnout is higher among doctors, and especially emergency doctors, than in the general workforce.

International studies show that burnout is dangerous for doctors and can be fatal for patients. A systematic review found doctors with burnout were twice as likely to provide unsafe care, and a study of almost 8,000 surgeons suggested burnout doubled the odds of major medical errors.

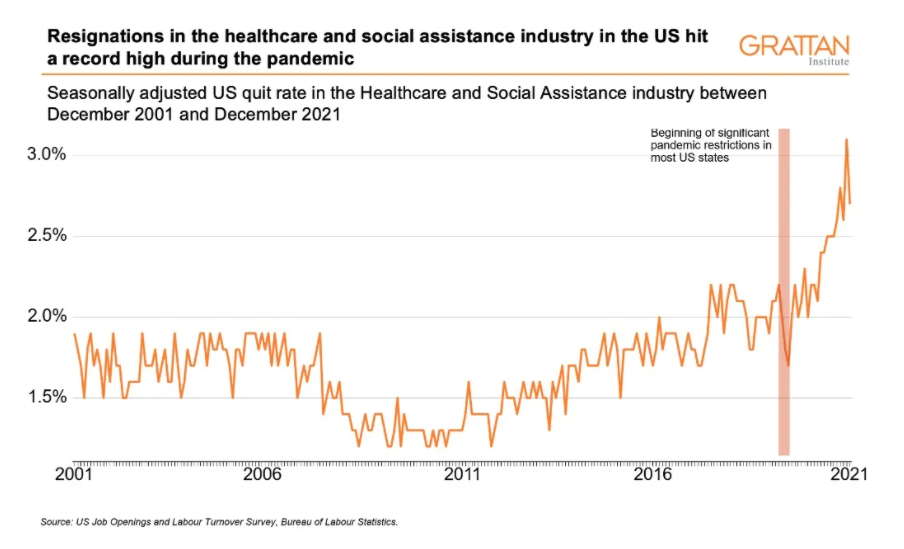

The ‘Great Resignation’ story originated in the United States, and the evidence shows that resignations have increased there. The US Bureau of Labour Statistics reported that monthly healthcare resignations rose to their highest level on record last year (see Figure 1).

Another US survey from last September found 18 per cent of healthcare workers had quit their job since the pandemic began, and nearly one third cited burnout as the reason.

The Australian data have more gaps.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics publishes resignation statistics, but the most recent data only goes to February 2021. Nurse and doctor registrations have only been reported to December 2021. Neither source showed an increase in workers leaving, even in the states and occupations hardest hit by COVID. And both miss the more recent spike in case numbers when stress and resignations may have peaked.

The data on burnouts is even more mixed. With higher patient loads and staff shortages during the pandemic, an increase in burnout might be expected. However, the best longitudinal data available, which comes from regular US surveys, suggests it stayed stable or decreased – even for intensive care and emergency doctors.

COVID-19 workload increases may have been balanced out by stronger supports for workers, such as counselling services. And healthcare workers reported feeling that they accomplished more during the COVID crisis.

What should be done

Current efforts are overly focused on the individual, too often essentially blaming the victim. Burnout strategies need to recognise that there are common stressors. Hospitals can reduce burnout by conducting debriefing sessions after stressful events, and training staff on burnout prevention strategies.

Most healthcare workers are aware of prevention strategies but face practical barriers to implementing them. Strategies such as exercising and catching up with friends are difficult when working night shifts.

A systematic review found a better approach is to tackle the causes of workplace burnout. Effective strategies include increased availability of supervisors, protected time to ensure that time off is really time off, and shared scheduling to avoid long stretches of uninterrupted shifts.

Of course, hospitals can only make these improvements if healthcare workers are available. That’s why governments need to act as well.

There are staff shortages in numerous rural hospitals, and Australia may have a shortage of 120,000 nurses by 2030. Governments need to work with training bodies to better coordinate workforce planning and fill these workforce gaps.

If there was a training course that could halve healthcare workers’ odds of harming patients, it would be made mandatory. Prevention of burnout should be treated with the same urgency by governments and all health sector employers.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO