Published at The Conversation, Friday 3 May

Stagnant wages are a huge issue in this election campaign.

So it is odd that both major parties are hanging onto a policy that will take more out of workers’ pockets.

Lifting compulsory superannuation contributions from 9.5% to 12% in five annual steps between and 2021 and 2025, as Labor insists on and the Coalition says it supports, will take up to an extra 0.5% out of wages each year for five years.

If wage growth would otherwise be 2.3% per year, as it is now, instead wages growth for five years would be closer to 1.8%. After the five years, wages would be up to 2.5% lower than otherwise.

And it would cost the budget, which is one of the reasons neither side is anxious to do it until 2021. Super contributions are taxed more lightly than wages.

In return, workers will get more super, which won’t help them much.

More super means lower wages

Australia’s superannuation system requires employers to make compulsory contributions on behalf of their workers.

Right now that contribution is set at 9.5% of wages and is scheduled to increase incrementally to 12% by July 2025. Federal Labor recently recommitted to increasing compulsory super to 12% of wages. It’s also Coalition policy.

Although the government requires employers to pay super on top of salary, it doesn’t usually come out of their pockets.

The overwhelming evidence is that higher super contributions are paid for by lower wages.

The Henry Tax Review and others have found this is exactly what happens.

The Parliamentary Budget Office came to the same conclusion in April this year: if compulsory super contributions go up, wages will be lower than they would be otherwise.

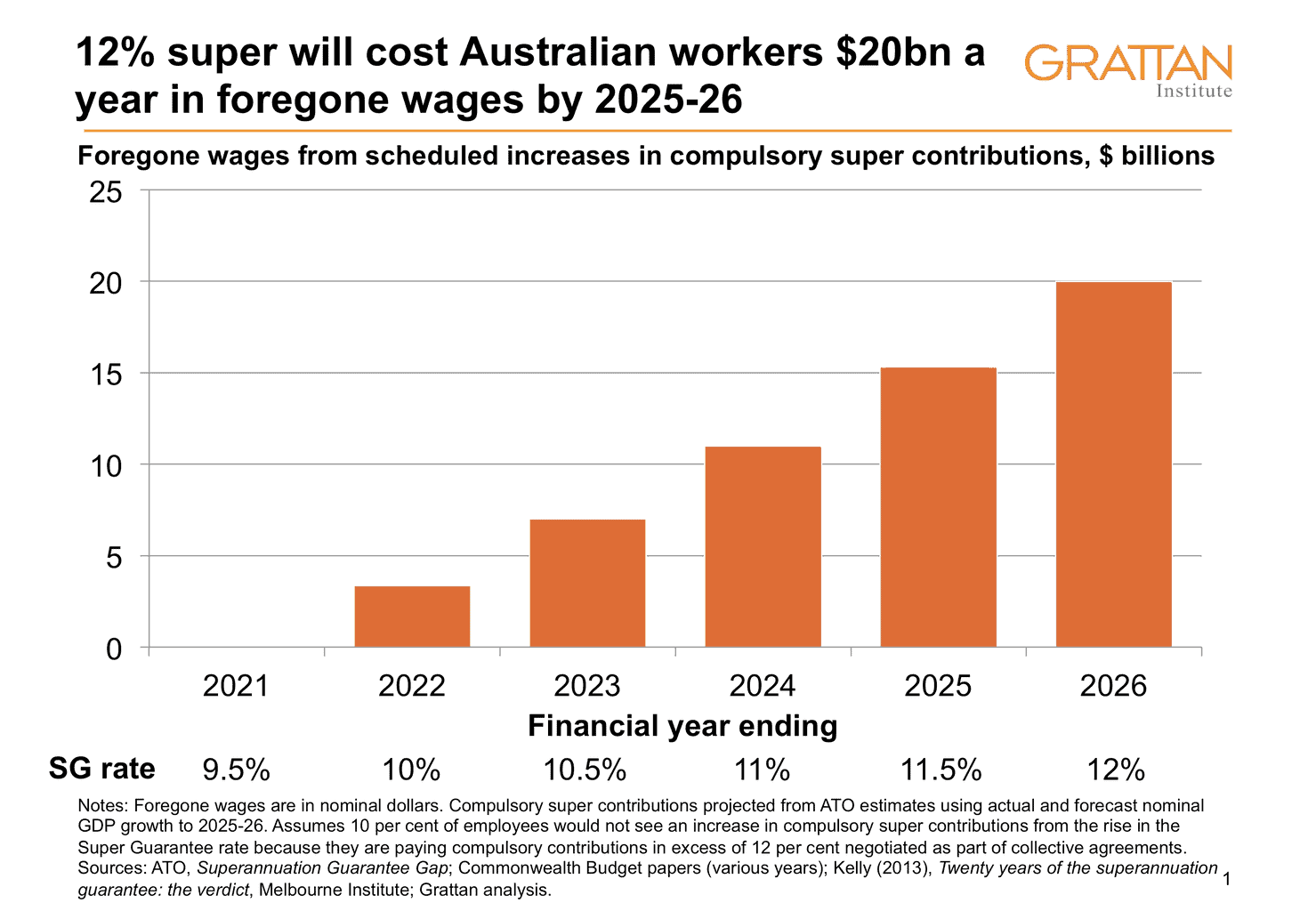

And the cut to wages from raising compulsory super from 9.5% to 12% will be big. Really big. Our calculations show that by the time it is fully implemented in 2025-26, a 12% Super Guarantee will strip up to an extra A$20 billion from workers’ wages each year, or close to 1% of Australia’s gross domestic product.

Most workers don’t need more super

Nor are higher super contributions actually needed.

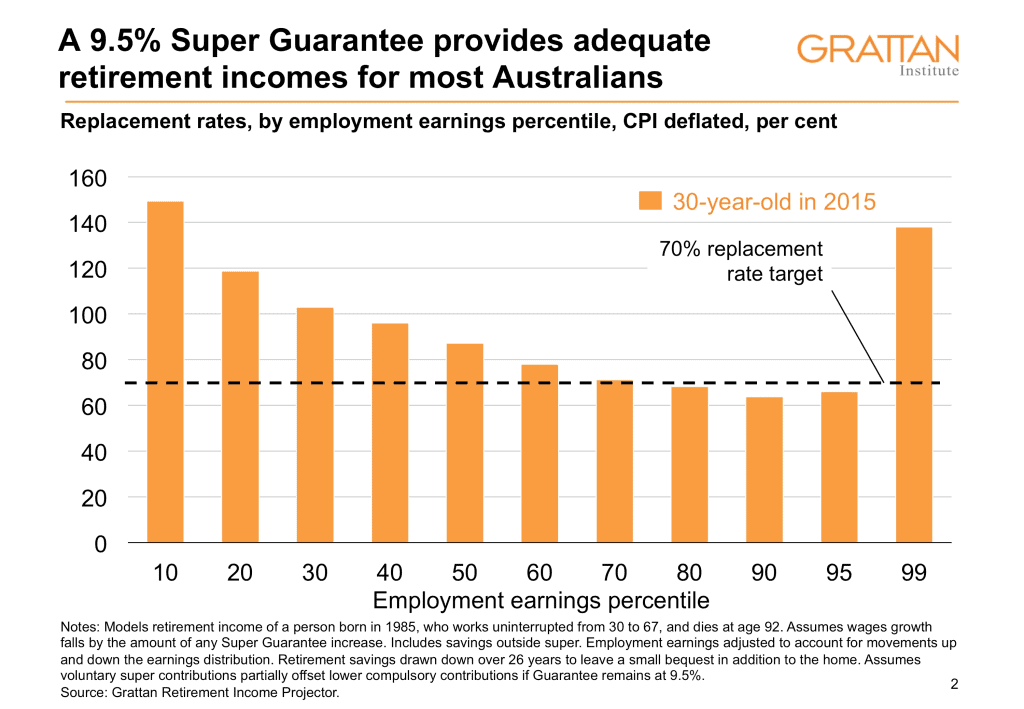

Grattan Institute’s latest retirement income projections show that most Australians are already on track for adequate retirement incomes.

Most workers today can expect a retirement income of at least 87% of their pre-retirement income if compulsory super contributions are left at 9.5%.

That’s well above the 70% benchmark endorsed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and more than enough to maintain pre-retirement living standards.

Modelling commissioned by the super industry that suggests otherwise is based on flawed assumptions.

Even workers in their 40s and 50s today – many of whom didn’t benefit from the present high rate of compulsory super contributions for their entire working lives – can expect a retirement income of more than 70% of their pre-retirement incomes.

Right now, at the present rate of super contributions, many low-income Australians are on track to get a pay rise when they retire, through a combination of the age pension and their compulsory superannuation savings. A full-time worker on the minimum wage can expect a retirement income almost 20% higher than their present after-tax wage.

Forcing low-income workers to save even more for retirement while reducing their incomes while working will leave them worse off overall.

And more super won’t help much in retirement

Superannuation lobby groups are pushing the major parties to lift compulsory super contributions to 12% as soon as possible.

They point to the higher super balances workers will have at retirement if compulsory super contributions are increased.

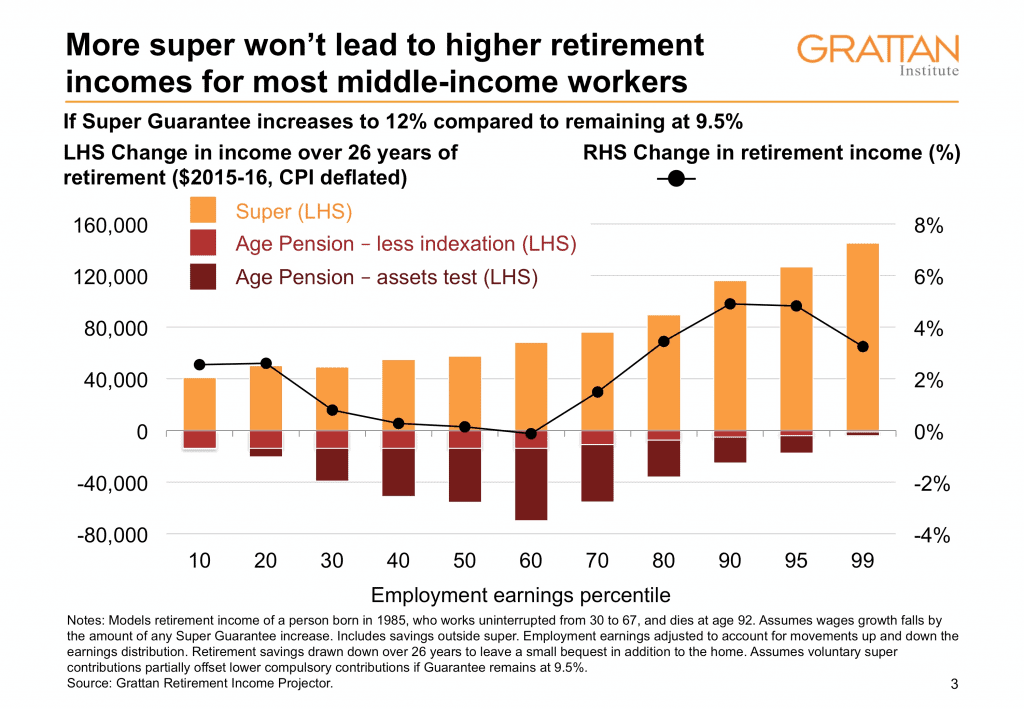

But it’s a misleading story. More super at retirement is only useful if it actually translates to higher incomes in retirement. And for most low and middle income earners, it won’t do it much.

For most Australian workers, lower age pension payments would largely offset the increase in their retirement income from super savings, leading to little or no change.

There’s more. The age pension is indexed to wages. Boosting super contributions would suppress wages growth, making the age pension climb more slowly, hurting both retirees in future and retirees today.

Australians receiving the age pension today should be the most fervent opponents of a lift in compulsory super contributions.

And for many Australian workers, sacrificing a greater share of their wages in exchange for little or no increase in their retirement incomes will leave them with lower lifetime incomes than they would otherwise have.

Instead increasing compulsory super would primarily boost the retirement incomes of the top 20% of Australians who gain access to extra super tax breaks, while costing those of us working up to $20 billion per year in lost wage rises, and the budget more than $2 billion per year in lost tax.

And it would be a long time before the tax revenue lost through super tax concessions saved the budget enough money on pensions to pay its way. Our projections put the break-even point at 2060 — by which time there will be 80 years of budget costs to pay back before the whole exercise has saved the government money.

The benefits of increasing compulsory super to 12% are tiny. The costs, at a time of unusually low wage growth, would be keenly felt, and at a time of unusually low economic growth, could have broader consequences.

Both Labor and the Coalition should think again.

The Productivity Commission has begged for an independent inquiry into whether 12% is needed, before the increases start.

At the very least, both sides should commit to postponing or varying the planned increases if there is a fair chance that they will lead to further wage stagnation. That’s how it is today, and may well be in four years time.