Published at The Conversation, Tuesday 30 October

It’s already started. We may be only entering the formal election campaign in Victoria tonight, but massive transport announcements are in full swing from the state Labor government, the Coalition opposition and the Greens. And with an election due next March in New South Wales, we can be sure the major parties in that state won’t be far behind.

Expanding the capacity of the transport network always gets far more attention than other ways of managing a fast-growing population. In reality, though, governments have a far bigger menu of options to keep Australia’s capital cities moving – and they should use them all.

Big spending promises all round

The swag of promises in Victoria to date has been big on rail. The Andrews government would, if returned, build a 90km suburban rail loop connecting all major suburban lines. Work is to start in 2022 at an announced cost of A$50 billion.

A Matthew Guy-led Coalition government would, if elected, build high-speed-rail to regional cities. The first trains would come into operation within four years, at an announced cost of A$15-19 billion.

And the Greens? They would upgrade suburban rail signalling and add 100 extra high-capacity trains, at a cost of A$8.5 billion.

If talkback radio is any guide, these plans are popular. People love the idea of a magnificent new rail system that perhaps they’ll use or, more likely, that they hope all those people who currently clog up the roads will use instead. After all, Melbourne is a very car-dependent city. And, with three-quarters of all the jobs dispersed all over the city, that’s unlikely to change much any time soon.

People also love big new infrastructure because it feels as though it comes for free. While a politician may have to pick just one from a menu of large projects, voters don’t have to confront this kind of choice.

Rather, we face the difference between a new station or service near our home, or no such new station or service. If you are the beneficiary of a new rail service, you may support the candidate promising it. By contrast, the losers are dispersed, and it’s hard to get too agitated about services we never had.

Look more closely at what is happening

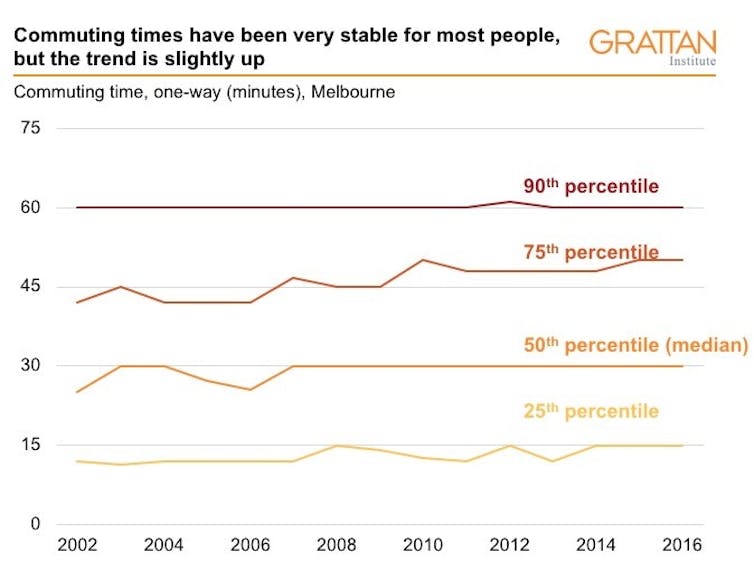

But new transport infrastructure is far from the only way to cope with population growth. Even though Melbourne has had extremely high population growth, averaging 2.3% a year over the five years to 2016, commuting distances and times have remained remarkably stable.

The median commute distance for Melburnians barely increased, from 8.6km to 8.7km, over the five years to the most recent Census in 2016. The median commute time has remained at 30 minutes each way since 2007.

Source: Grattan analysis of HILDA (2016), Author provided

These stable commute times and distances have coincided with a period of only limited new infrastructure construction. Victoria’s additions – Regional Rail Link, Peninsula Link and the M80 Ring Road – are modest compared to Queensland and NSW’s. The road stock in Melbourne increased by 4.3% over the five years to 2015, significantly less than the population increase of 11.9%.

The A$1.3 billion CityLink Tullamarine widening project finished recently, and the A$8.3 billion level crossing removal project is more than half-completed, but these projects are too new to explain the remarkable stability of commutes over the period of booming population.

Despite only modest new infrastructure, people have adapted. Some have changed job or worksite, and working from home is on the rise. Some people moved house, or even left the city. And some changed their method of travel, leaving the car at home and catching the train, tram or bus to work. Other people simply accepted a longer commute, at least for a time, and particularly if they were earning more.

Of course, not everyone is better off when the population grows rapidly. Some people elect not to take a new job that’s too far from home; some pay higher rent, or cannot afford a place they once could have. But the lesson from Melbourne is that people are not hapless victims of population growth, depending for their well-being on governments building the next freeway or rail extension.

So what are the best ways to help cities cope?

The Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018 recommends that governments work with, not against, the adaptations that people make. Here are three ways state governments can help:

1. They should stop making it so hard to move house, by replacing stamp duty with a broad-based land tax.

2. They should stop locking new residents out of their preferred locations, by combining a relaxation of zoning restrictions on residential density with clear assignment of on-street parking rights.

3. The incoming governments of Victoria and NSW should introduce time-of-day road congestion charges in the most congested parts of Melbourne and Sydney (offset by a cut to vehicle registration fees), with the funds earmarked for public transport improvements.

Let’s see what the vying parties can do.

![]()