Home ownership is slipping out of reach for many younger, poorer Australians. Many older Australians who rent are also being left behind. A national shared equity scheme would help level the playing field.

Whichever party wins the 2022 federal election should introduce a national shared equity scheme to help arrest declining rates of home ownership among poorer Australians of all ages.

Home ownership is falling fast among poorer Australians of all ages

Within living memory, all Australians had a reasonable chance to own a home. But now, for many Australians the Great Australian Dream of home ownership is becoming a nightmare.

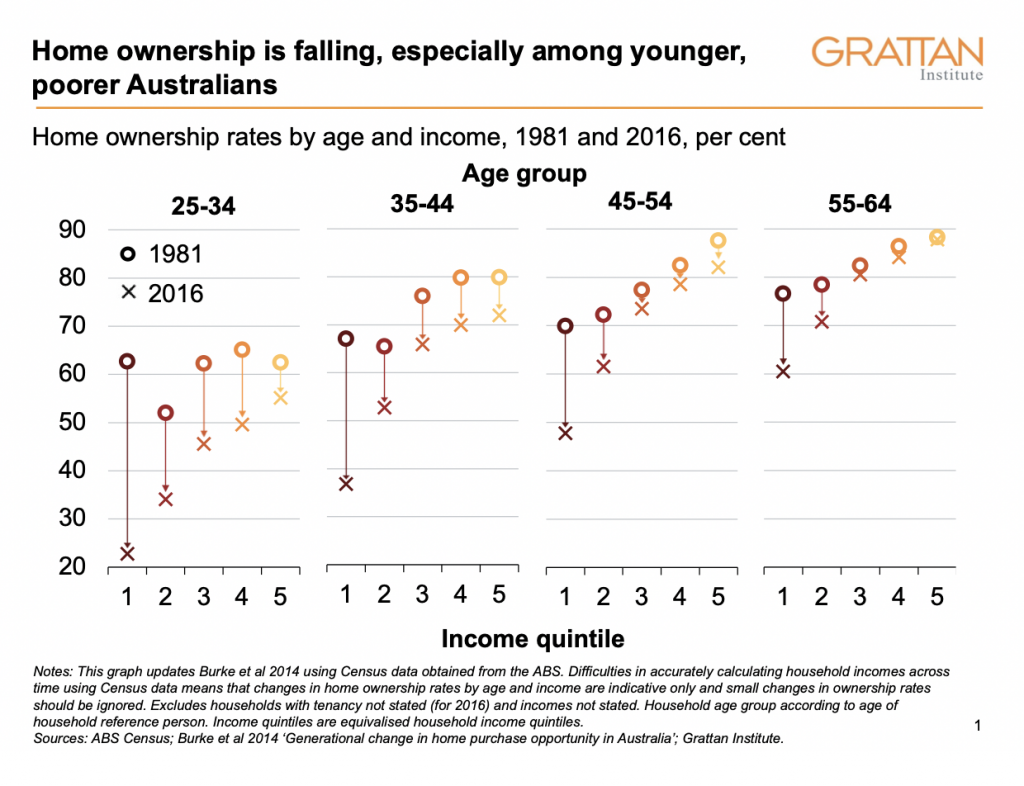

Home ownership rates are falling fast, especially among the young and poor. Between 1981 and 2016, home ownership rates among 25-34 year-olds fell from more than 60 per cent to 45 per cent, and among the poorest 40 per cent of that age group, it has more than halved, from 57 per cent to 28 per cent.

Home ownership is also falling among poorer older Australians. Among the poorest 40 per cent of 45-54 year-olds, just 55 per cent own their homes today, down from 71 per cent four decades ago.

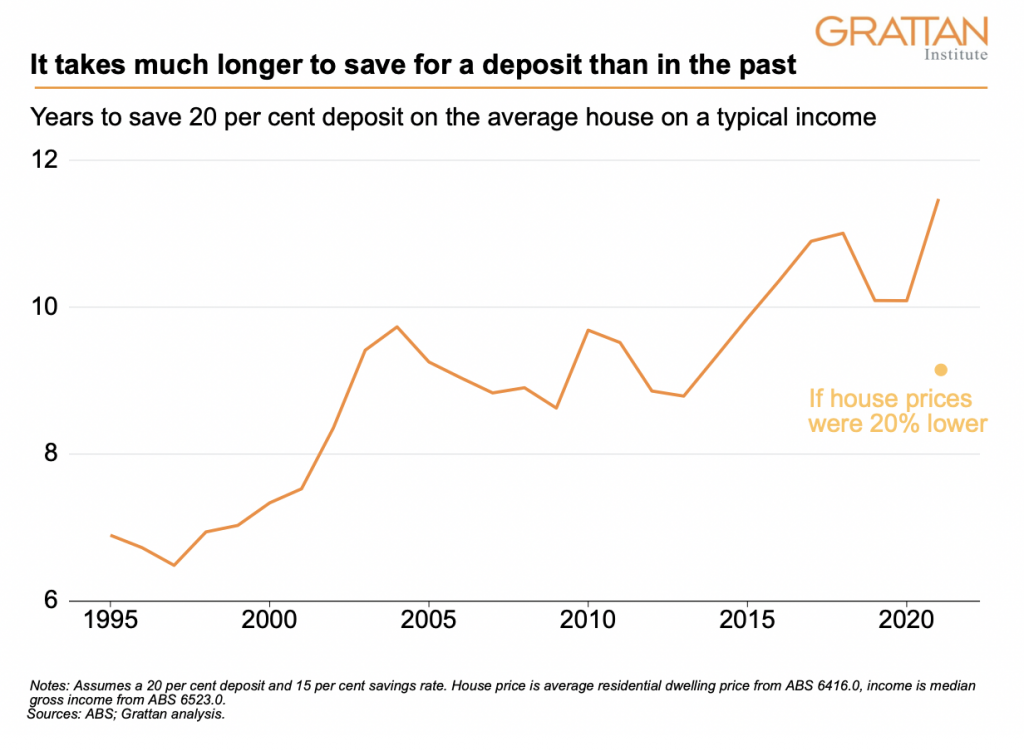

Home ownership is falling because it takes much longer today to save for a deposit. In the early 1990s it would take the average Australian about seven years to save a 20 per cent deposit for a typical dwelling. Now it would take almost 12 years. Unsurprisingly, a growing share of Australians are relying on the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ for a deposit.

Meanwhile older renters with a deposit won’t be in the workforce long enough to pay off a home by the time they retire, even at today’s record-low interest rates.

Even if federal and state governments adopt much-needed reforms to lift supply and reduce demand, house prices are likely to remain high, relative to incomes, due to the long-term decline in interest rates. While interest rates will rise, few expect them to return to the levels of 10-to-20 years ago.1

Even if house prices were to fall by 20 per cent from current levels, it would still take the average Australian about nine years to save a 20 per cent deposit on the average home.2 Therefore, the deposit hurdle is likely to remain a problem for younger, poorer Australians without a ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’.3

Without policy change, more retirees will rent in future

Today’s younger renters are tomorrow’s renting retirees. Past Grattan Institute research estimates that by 2056, just two-thirds of retirees will own their home, down from nearly 80 per cent today.

The Federal Government’s 2020 Retirement Income Review showed most homeowners are on track for a comfortable retirement. But Australians who rent are facing an increasingly bleak future.

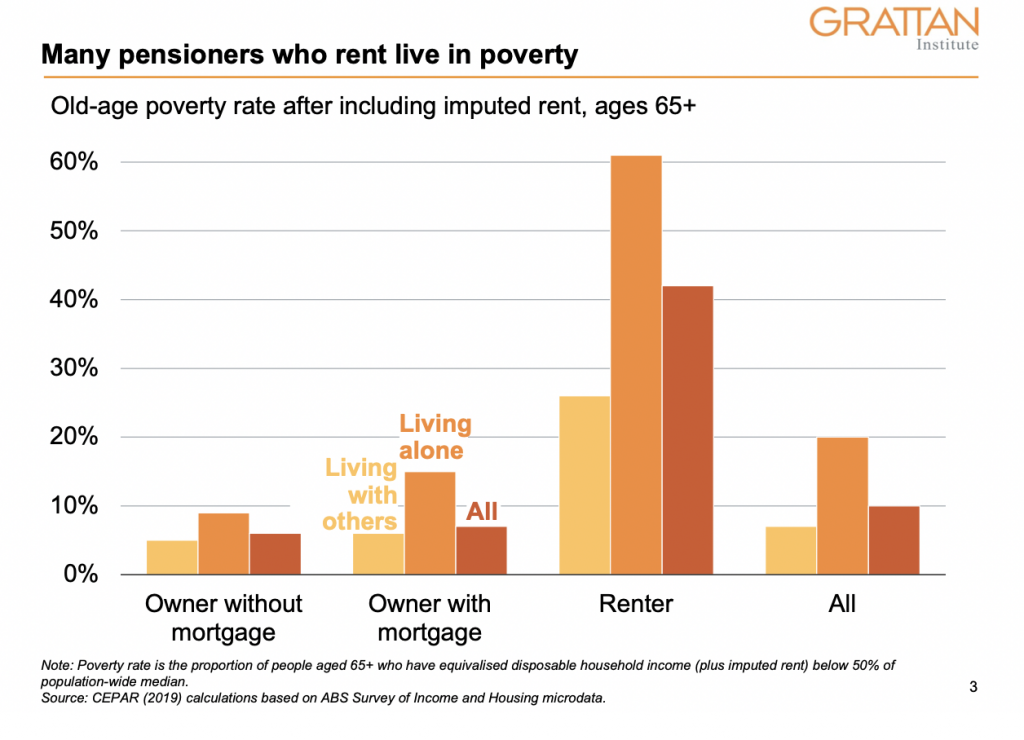

Senior Australians who rent in the private market are much more likely to suffer financial stress than homeowners, or renters in public housing. Nearly half of all retired renters are in poverty – with incomes below half the median. Their numbers will only grow as fewer retirees in future own their homes. Older women are especially vulnerable: women aged over 55 are already the fastest growing group to suffer homelessness in Australia.

Home ownership shouldn’t be the aim for everybody. But older Australians who don’t own their home by the time they retire are often punished by the assets test for the Age Pension, which ignores housing equity but captures other savings in full. And Rent Assistance – paid to pensioners that rent – remains woefully inadequate.

A shared equity scheme would help level the playing field for homebuyers

A national shared equity scheme would help level the playing field for first homebuyers and arrest the decline in home ownership among poorer Australians of all ages.

Under the scheme I propose, the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) would co-purchase up to 30 per cent of the home value, taking a proportionate share of any profits when the home is sold.4 Purchasers would borrow the remaining funds from a private lender, provided they have at least a 5 per cent deposit.5 Homeowners would also be able to buy out the government’s equity stake – in 5 per cent increments – at the prevailing market price.

Consistent with longstanding state schemes, the NHFIC would not charge rent or interest to participants.6 However, purchasers would be required to cover all costs associated with buying or selling a home, such as conveyancing and stamp duty, as well as ongoing costs such as council rates and maintenance.7

The scheme should be restricted to people purchasing their principal place of residence.8 Participation would be restricted to singles with incomes below $60,000, and couples with combined incomes below $90,000.9 Regional price caps would mean participants could only buy below-median priced homes in their city or region.10

The scheme should start with a trial of 5,000 places a year for the first three years. At that point the scheme should be reviewed, and if deemed successful, expanded.

Several states already have shared equity schemes, but a national scheme is needed.11 Existing state schemes are typically small, and often limited to public housing tenants or to purchasing homes solely from government-run developers.

The federal government has lower borrowing costs than state governments, and is much better placed than private providers to secure the long-term financing required to manage the scheme.12 The National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation already offers various deposit guarantees. And the federal government will be on the hook for a larger bill for Commonwealth Rent Assistance payments should home ownership fall among retirees.13

In time a federal scheme could replace existing state schemes, or help fund them through a national partnership agreement.14

Shared equity would help many poorer Australians into home ownership

A national shared equity scheme would help younger Australians get into the housing market faster, especially those without access to the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’. Buyers would be able to borrow less for their first home – reducing the level of risk they take on – especially since interest rates are likely to rise from here.15 Other first home buyers may use the scheme to secure a larger home that can accommodate a growing family, avoiding the need to pay stamp duty twice if they upgrade in future.

A national shared equity scheme would also help many older Australians, especially many older single women.

Many older Australians who rent have more than enough savings for a deposit but can’t buy because they won’t stay in the workforce long enough to pay off the mortgage by the time they retire.16 For instance, about 60,000 renting households aged 45-64 have financial assets (excluding their super) of more than $200,000 (singles) and $300,000 (couples). A shared equity scheme could help many of this group into home ownership, allowing them to pay off any remaining loan with their super at retirement.

Shared equity could help couples to remain in home ownership if they separate. The home is typically a family’s largest asset and splitting the equity in the home upon separation often requires it to be sold. Separating couples then often lack the assets to each purchase a new home, especially since they must pay stamp duty again.

Just 34 per cent of women who separate from their partner and lose the house manage to purchase another home within five years, and only 44 per cent do so within 10 years. By contrast, 42 per cent of separating men buy a home within five years, and 55 per cent within 10 years.17

Unsurprisingly, older women that have separated or divorced are more than three times as likely to rent at age 65 years than married women, whereas separated men are more than twice as likely.18 And separated women typically have just two-thirds the assets of separated men in retirement.19

Finally, shared equity could also help retired Australians when they downsize, because by unlocking home equity it would boost retirees’ living standards.

Any impact on house prices would be modest

Shared equity schemes can result in higher house prices, by adding to housing demand. But targeting schemes tightly at lower-income Australians and lower-priced homes would reduce the impact.

A well-targeted scheme, such as the one we are proposing, would have only a modest impact on house prices. Capping the scheme at 5,000 places a year in the early years would limit any short-term impacts. But even if the scheme were to eventually offer 10,000 shared equity loans a year, with each buyer purchasing a $500,000 home on average, the scheme would add at most $5 billion to housing demand in a $9 trillion housing market, and probably a lot less.20

The federal budget would probably benefit in the long term

A national shared equity scheme would expose the federal government’s balance sheet to some risk if house prices fell.21 But those risks would be modest. Were an average of 10,000 Australians to take up the scheme each year, the federal government could issue 80,000 loans by 2030, borrowing up to $12 billion (or 0.4 per cent of GDP in 2030) to finance the shared equity stakes.22

A national shared equity scheme would have a small short-term budgetary cost as the government pays interest on extra government debt.23 But a national scheme is likely to be budget positive in the long term, should nominal house prices rise faster than the interest rate on government debt to finance the purchases – as they have in the past.24 Existing state schemes, such as WA’s Keystart scheme, have typically turned a profit for state governments.

Helping lower-income borrowers to enter the housing market, with as little as a 5 per cent deposit, could result in more bad debts in future. But existing shared equity schemes report low rates of non-performing loans, even when house prices have fallen.

But even if the federal and state governments make the hard choices to improve housing affordability by lifting supply and reducing demand, house prices are likely to remain much higher, relative to incomes, than they have been over most of Australia’s history.

Falling home ownership is a big problem for Australia. A national shared equity scheme would help keep the dream of home ownership alive for many Australians.

This document uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The unit record data from the HILDA Survey was obtained from the Australian Data Archive, which is hosted by The Australian National University. The HILDA Survey was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views based on the data, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Australian Government, DSS, the Melbourne Institute, the Australian Data Archive or The Australian National University and none of those entities bear any responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of the unit record data from the HILDA Survey provided by the authors.

Footnotes

- RBA Governor Phil Lowe expects the neutral cash rate – the rate of interest where monetary policy is neither expansionary (lowering unemployment) or contractionary (lifting unemployment) – is likely to be about 2.5 to 3.5 per cent in nominal terms, or between 0 and 1 per cent in real terms. That’s well below the RBA’s average nominal cash rate of 4.1 per cent since the Bank formally adopted an inflation target in mid-1993.

- For instance, past Grattan Institute analysis has estimated that wholesale state land-use planning reforms could result in house prices falling gradually by up to 20 per cent over a decade. Reforming the tax treatment of housing would have a smaller, but more immediate, effect on house prices.

- The NSW Intergenerational Report also projects the deposit hurdle to fall only modestly, from 11.5 years to save a deposit in 2019-20 to about 10 years by 2060, reflecting slower growth in house prices in the years ahead. See NSW Intergenerational Report 2021-22, p. 65.

- For instance, if the government takes the maximum 30-per-cent stake in the home, they will take 30 per cent of any capital gains (or losses) upon sale of the home. If the government only takes a 15 per cent stake, they only take 15 per cent of any gains (or losses) upon sale of the home.

- Participants in the Victoria’s Government’s new shared equity scheme, announced in October 2021, must secure a loan from a private bank.

- For example see Western Australia and South Australia. The federal government would be foregoing rental income of $3,000 a year on a 30 per cent equity stake on a $500,000 home, assuming a 2 per cent net rental yield. However this would be offset by purchasers wearing the full upfront costs of any stamp duty payable, and all ongoing maintenance costs.

- First homebuyers receive discounts on stamp duty in most states.

- This would include people who have owned a home before previously. The scheme would not be open to people who already own an investment property.

- Thresholds are for gross (i.e. pre-tax) incomes. About 57 per cent of all Australian singles aged 25-64 and 25 per cent of couples earn sufficiently low incomes to meet the income threshold. About 63 per cent of single renters and 45 per cent of couple renters have incomes below the thresholds. Grattan analysis of ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2019-20.

- For instance, a $800,000 price cap across Australia, with lower caps in lower-priced cities and regions, would ensure participants could purchase at least 25 per cent of houses everywhere except Sydney, and more than 50 per cent of apartments in all major capital cities.

- The WA, SA, and Tasmanian governments offer shared equity schemes, but offer comparatively few shared-equity loans each year. The ACT government offers a land rent scheme. Victoria announced a new scheme in late 2021. In Queensland, shared equity is available only to public housing tenants. No scheme currently exists in NSW.

- Shared equity is typically a long-term investment lasting 20-to-30 years, for which private capital is often very expensive. Private shared equity providers may also be disadvantaged by progressive state land taxes which apply to the entity’s total land holdings, rather than their holding in each property. Therefore private entities, such as super funds or other investment vehicles, that hold a lot of shared equity would be exposed to a large land tax liability at the top land tax rate, making it uneconomic to hold the housing equity. One benefit of a government-run scheme is that the federal government is exempt from state tax taxes.

- Recent AHURI research estimated that the number of households eligible to receive Commonwealth Rent Assistance would rise by 61 per cent, from 952,000 in 2011 to 1.5 million in 2031.

- A similar arrangement already exists for first home deposit grants, which are funded by the federal government but administered by the states.

- Many first home buyers have not taken up higher leverage loans because they are risk-averse The typical leverage of a first home buyer has remained remarkably constant, at about 83 per cent since 2000, even though banks loosened lending requirements and became more prepared to provide high-leverage loans.

- The Federal Government recently announced a ‘Family Home Guarantee’ to support single parents to purchase a home with just a 2 per cent deposit without lenders’ mortgage insurance. However, participants still need a sufficient income to cover the remaining 98 per cent of the purchase price.

- Grattan analysis of HILDA (various years).

- More than 25 per cent of women that are separated or divorced rent at age 65, compared to just 8 per cent of married women. See Retirement Income Review, Chart 3B-26.

- The average separated single woman aged 65+ has $205,000 in net wealth, compared to $311,000 for the average separated man. See Retirement Income Review, Table 3B-4.

- Long term house prices are determined by the balance of demand and supply for the total stock of housing. Assumes no buyers would purchase otherwise. In practice not all purchases will be additional, because some users of the scheme may otherwise purchase anyway. There are typically a little over 100,000 first homebuyers in Australia each year.

- House prices have fallen year-on-year in about one in every four years since 2003.

- These figures assume no applicants sell their home or purchase additional equity over that period. The total outstanding debt by 2030 is therefore likely to be lower than these figures suggest.

- Assuming 5,000 loans a year, and a government borrowing costs of 3 per cent, and an average processing cost of $1,000 per shared equity application, the total cost of the scheme would be around $220 million over the first four years. These debt interest servicing costs would hit the underlying cash balance, whereas any accrued capital gains for the federal government would only hit the federal budget if the purchaser buys out the government’s equity stake, or when the home in eventually sold.

- For instance, Australian house prices have risen by an average annual compound growth rate of 5.3 per cent each year since September 2003. By comparison, 10-year Australian government bonds have yielded an average of 3.84 per cent over the same period. The federal government could also lock-in low interest rates at currently low bond yields.

Brendan Coates

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO