Published at The Conversation, Monday 23 July

Recent Australian migrants are buying into the Great Australian Dream of home ownership. But rates of home ownership among recent migrants are falling, as they are among all Australians. Unless we build enough housing to match Australia’s growing population, all Australians, including migrants, will pay the price.

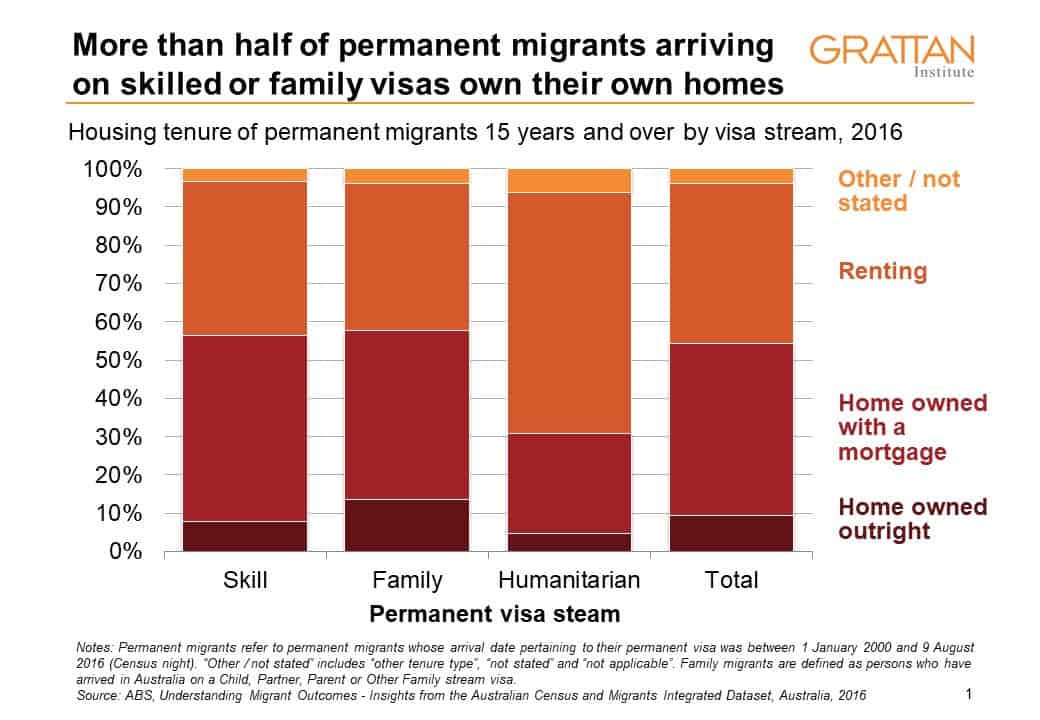

A recent data release by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows 54% of permanent migrants aged 15 and over own their home, compared to 67% of Australians overall. Since migrants tend to be younger than native-born Australians, and younger people are less likely to own their home, migrants have broadly similar rates of home ownership to native-born Australians of the same age.

And the facts do not support the idea that substantial numbers of migrants to Australia are relying upon on public housing. Just 2% of all permanent migrants arriving since 2000 are living in public housing, compared to around 4% of the overall Australian population.

Home ownership is highest among migrants granted permanent residency under the skilled (57%) and family (58%) visa streams, compared to just 31% among those on humanitarian visas. Comparatively high rates of home ownership among permanent migrants is unsurprising: skilled migrants in particular tend to earn higher incomes than native-born Australians.

Permanent migrants also appear to be relatively well housed. Just 13% of permanent migrants have too few bedrooms in their home, compared to 22% of all Australians. But one-third of humanitarian migrants granted permanent residency need more bedrooms.

But recent migrants are becoming less likely to own their homes. Only one-third of arrivals over the past five years own their home today. That’s down from 41% in the period before the 2011 Census.

The fall in home ownership has been highest among skilled migrants: just 31% of recent skilled migrants owned their homes, compared to 41% of recent skilled migrants at the time of the 2011 Census. In part this may be because migrants over the past ten years have been younger than migrants in the past. But it also shows that migrants are not immune to the housing affordability woes affecting all Australians.

Newly arrived migrants have always been less likely to own their own homes. Only one-third of migrants arriving since 2012 own their home, compared to almost two-thirds of permanent migrants who arrived in Australia before 2012.

But it’s clear that worsening affordability is a major culprit. The prices of cheaper homes have grown much faster than for more expensive homes over the past decade. This has made it much harder for first home buyers to buy a home.

While record low interest rates make mortgage repayments affordable today, these are likely to rise. And it now takes around ten years to save a 20% deposit for an average dwelling, up from around six years in the early 1990s.

We haven’t built enough homes

While interest rates are the largest driver of rising house prices in recent years, a lack of new homes hasn’t helped. Over the last decade, home building did not keep pace with increases in demand from rising population, let alone rising incomes.

Migration increased substantially from about 2006. Australia’s population started to grow by around 350,000 per year, rather than the 220,000 per year that was typical in the preceding decade.

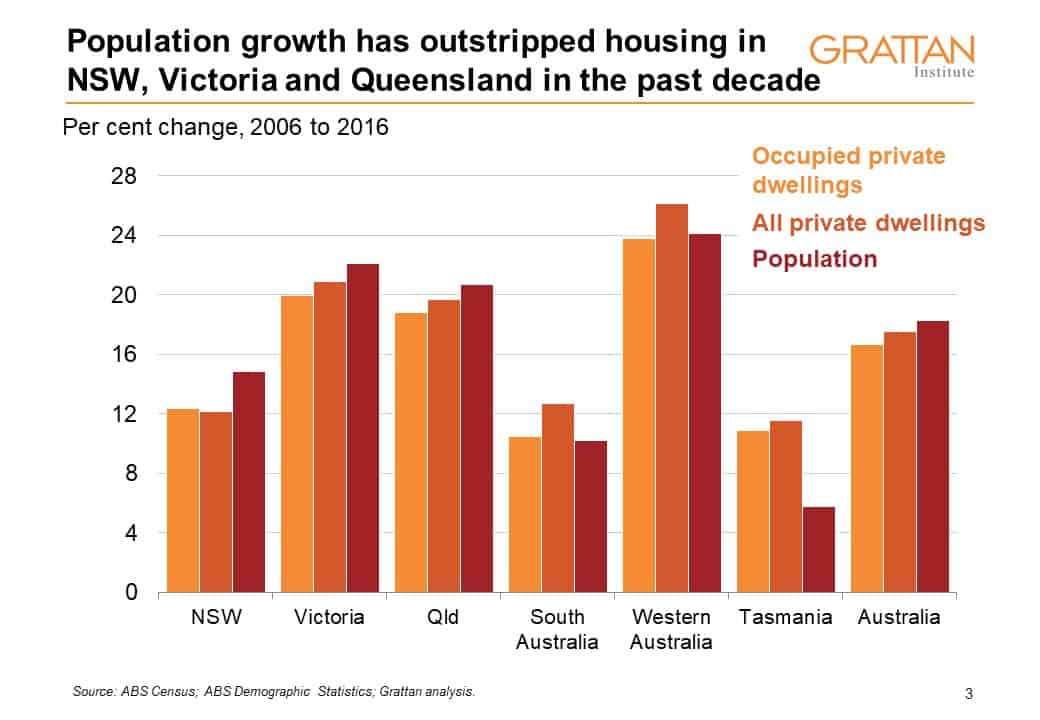

Dwelling construction fell behind population growth, only picking up from 2013. According to Census data, population growth outstripped growth in the number of homes across Australia between 2006 and 2016, and especially in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland.

Recent analysis claiming that housing construction outstripped population growth over the period 2005-06 to 2014-15 uses building approvals without accounting for the demolition of existing homes. It also ignores how rising prices and worsening affordability have prevented many younger Australians from moving out of the family home to form households of their own.

The imbalance between demand and supply has consequences. Younger and poorer households are paying more for housing. Owning a home depends more on who your parents are, a big change from the early 1980s.

Only in the past couple of years has housing construction got close to matching population growth; the backlog of a decade of undersupply remains. Development at today’s record rates is the bare minimum needed to meet record population growth built into Sydney’s and Melbourne’s housing supply targets over the next 40 years.

What should we do?

In post-war Australia, record rates of home building matched rapid population growth. House prices barely moved.

Building more housing will improve affordability the most – but slowly. Even at current record construction rates, new housing increases the stock of dwellings by only 2% each year. But building an extra 50,000 homes a year nationwide for a decade would lead to national house prices being around 10-15% lower than otherwise, and by more if most homes were built in our major cities.

State governments need to fix planning rules to allow more housing to be built in inner and middle-ring suburbs. More small-scale urban infill projects should be allowed without council planning approval. And state governments should allow denser development “as of right” along key transport corridors – that is, without requiring approval in designated zones.

The Commonwealth can help by providing financial incentives for these reforms.

Migrants are often blamed for Australia’s housing woes, and there’s a clear link between strong migration, constrained housing supply and rising prices. But the new data show that recent migrants are also suffering from worsening housing affordability. And housing demand from immigration shouldn’t lead to higher prices if enough dwellings are built to match Australia’s growing population.

![]()