More GPs won’t be enough to solve the Medicare crisis

by Peter Breadon, Danielle Romanes, Lachlan Fox

Australians are getting older, sicker, and harder to treat. This isn’t news to GPs, who say they are overwhelmed with demand and frustrated with a rigid system that doesn’t support them.

To improve general practice, the Albanese government has set aside almost a billion dollars and convened a Strengthening Medicare Taskforce to advise how to spend it. Many people argue recruiting more GPs is the best path forward.

But as a new Grattan Institute report shows, Australia has plenty of GPs – although they’re not always in the right areas. What we lack are supporting clinicians to help GPs respond to a growing tide of chronic disease.

General practice is becoming more complex

One reason many GPs feel overwhelmed is because their patients are getting sicker. More patients have multiple conditions that need to be managed by their GP, and the proportion with more than one chronic condition has been estimated at nearly half.

Managing these patients is more complex and takes more time, but Medicare does not reward GPs for longer consultations. Average consultation length has been stuck at between 14 and 15 minutes since 2002, despite the increasing complexity of patients’ needs.

Australia has many GPs

To help general practices meet this demand, peak bodies have called for more GPs, and to attract them to the specialty through higher pay.

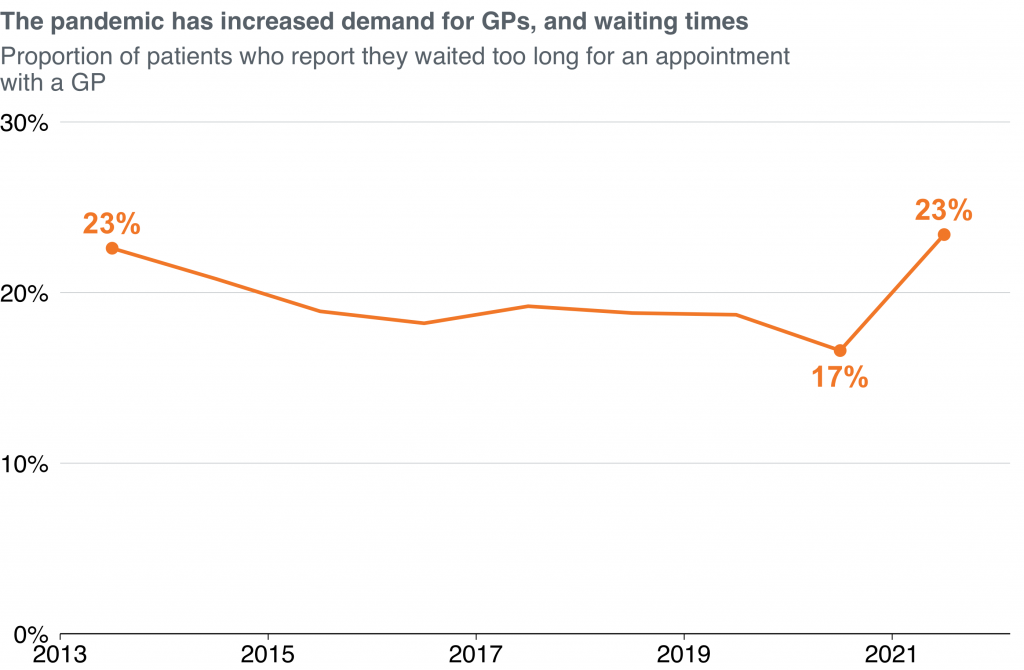

It’s true that many places in Australia, particularly some rural areas, don’t have enough GPs. And the pandemic has led to a surge in demand everywhere, with wait times spiking after years of steady decline.

But at a national level, almost all the indicators suggest GP supply is stronger than ever. As our report shows, Australia has more GPs per person than ever before, more GPs than most wealthy countries, and record numbers of GPs in training.

GPs need more support

While the supply of GPs has grown, more GPs alone can’t manage the rising tide of chronic disease, or the growing pressure on many general practices. Instead, we need to make general practice a team sport.

Team-based care is increasingly used in general practice overseas. But compared with similar countries, Australian GPs have little support.

About three-quarters of clinical staff in Australian general practice are GPs, with nurses making up almost all the remaining quarter. And those nurses don’t get to help as much as they want, with three-quarters saying they face barriers to using all their skills.

Other countries have different types of workers that Australia lacks. Germany has about 400,000 medical assistants, providing administrative and clinical support in general practice, while Australia has only about 100. England has about one supporting clinician for every GP, three times as many as Australia. In the United States, nurse practitioners and physician assistants deliver about 11% of all medical services outside hospitals. In Australia they would deliver less than 0.1%.

Team care is good for everyone

Evidence overwhelmingly confirms these and many other clinicians can share parts of a GP’s load with the same safety and quality of care. Studies suggest well-implemented team care can improve quality of care, patient safety and health outcomes, as well as reducing demand on hospitals.

It also makes GPs’ jobs more manageable, impactful and satisfying. By sharing simpler care with other team members, GPs can spend more time working with more complex patients.

It also creates time for other types of work: planning, improving care, maintaining oversight of the team’s care, and consulting with other specialists. While a GP’s clinical work will be more complex, they will also have more time to do other vital aspects of their role.

Emerging trials in many states (such as the pharmacist-prescribing trials in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria) have also made it clear task-sharing is happening – with GPs, or without them.

Unlike these trials, our recommendations focus on bringing new workforces into general practice, not taking care out.

What needs to change?

GPs might think this sounds like a fantasy that would never work for them. That’s because for most clinics, it will only be possible if there are fundamental changes to how the system is run.

The first barrier is funding. General practices lose revenue if they have anyone other than a GP deliver care. Medicare does not fund practice pharmacists, physiotherapists, practice nurses, nurse practitioners or Indigenous health workers to work to their full skill level.

Other workforces, such as physician assistants, community paramedics and medical assistants, are not funded to provide care at all.

General practices should be able to opt into a new funding model which, as well as paying GPs for each appointment, gives them a budget for ongoing care of each patient. This would enable GPs to expand their team, and give them funding even when another team member is providing care. Most wealthy countries use this kind of funding model.

The second barrier is regulation. An independent commission should advise government on how different roles should be regulated, to make sure workers can safely use all their skills.

Finally, taking away barriers isn’t enough. As other countries have found, change needs financial support.

The federal government should use Strengthening Medicare funding to roll out 1,000 new nurses, physiotherapists, mental health clinicians, pharmacists and other allied health workers in the highest-need communities, to work in general practices alongside GPs, providing fee-free care.

The shift to team-based general practice won’t be easy. It will require changes in how practices are designed and operate, and enough funding, time and training for teams to work well together. This should be recognised with more funding and sustained expert support.

Although it will be hard, the payoff will be worth it. GPs will be free to choose a model with more support and more sustainable workloads. Government will be able to reduce the biggest gaps in access and outcomes. And patients will have more time with their general practice team, quicker access when they need it, and better care.

Peter Breadon

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO