Published at The Conversation, Monday 17 February 2014

This year is crunch time for Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s health policies. The financing and policy changes from the Rudd-Gillard government are finally taking effect and the National Commission of Audit threatens to take a scalpel to the nation’s growing health spend.

In today’s Medical Journal of Australia, I propose a three-point plan to ensure 2014 is a year of health reform, not regression:

- keep the Medicare promise of universal health care

- introduce policies in prevention

- reform the architecture of the health system.

Rudd/Gillard health reform

In the first flush of enthusiasm after the 2007 election, then prime minister Kevin Rudd established the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (of which I was a member) to conduct a wide-ranging review of the health system.

The commission reported in 2009, proposing important changes to the way hospitals were funded, among other recommendations. Rudd cherry-picked the recommendations, changed key ones in substantive ways and introduced new proposals based neither on evidence nor the commission’s report.

Rudd came unstuck and his centrepiece response – to make the Commonwealth the majority funder of public hospitals – was contrary to the commission’s recommendation and did not survive state hostility. The agreement negotiated by the Gillard government left existing funding shares in place for the vast bulk of hospital funding.

The big difference is that from 1 July this year the Commonwealth will pay 45% of the cost of growth from 2013-14 levels, with the caveat that growth is to be paid for at the “efficient price” at which hospitals treat patients. This casemix measure – with the price determined by the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority – is closer to what Rudd’s reform commission recommended in 2009. The Commonwealth growth share will increase to half from 2017.

Coalition’s health outlook

The 2013 election has again put health reform on the agenda but in a quite different way. This time a Commission of Audit is looking at health issues, with a “too much spending” lens. The initial audit report is due to be handed to government this week and will probably be released before the budget.

Apart from a general statement that support for health insurance was in the Liberal Party’s DNA, the government provided few specifics during the election campaign, running on a “trust us” campaign with promises to maintain front line services and trim bloated bureaucracies. Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s overarching commitment to lead a government of “no surprises and no excuses” provides an important context.

The media silly season set loose some policy hares, notably one based on a submission to the Commission of Audit promoting a compulsory A$6 co-payment for visits to general practitioners. Roundly condemned by most commentators and interest groups, including the Australian Medical Association, the proposal would reverse a policy direction of promoting bulk-billing established by Mr Abbott when he was Health Minister.

Co-payments run counter to international trends, which are to encourage primary care, and in any event they would be hard to implement. GPs already have the discretion to add out-of-pocket fees. But 82% of GP services are bulk billed, for those that pay out-of-pocket, the average payment is around A$30 per visit. GPs already tend to charge higher-income patients higher fees, so any increase in fees will obviously impact on poorer families.

The mandated A$6 co-payment would presumably be implemented with a simultaneous cut to the rebate, as bulk-billing GPs would now be required to introduce billing systems, many would respond with co-payment larger than A$6, further exacerbating the government’s political problem.

Blueprint for real reform

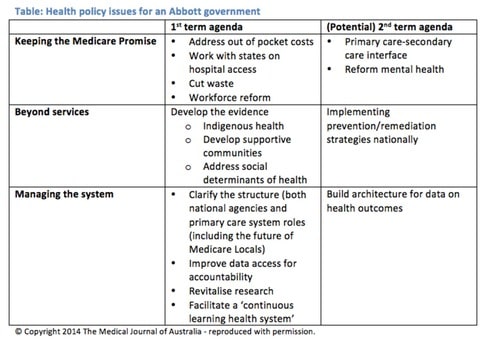

The Abbott government’s shaky start does not bode well for health policy in this term. Yet things need to be done and these can be categorised into three areas of reform: keeping the Medicare promise of universal health care; going beyond services to invest in preventing illness and managing the system architecture (see below).

Governments often focus solely on health service provision, as opposed to prevention. While Medicare has many strengths, the health system is marred by long waits, both for elective procedures and emergency care, and out-of pocket costs so high that many people already defer needed care.

There are ways to save money. But health policy should be about more than just services. Attention needs to be paid to public health and prevention – by focusing on improving indigenous health and creating healthy communities, for example.

Systems that will encourage external evaluation of policies and facilitate growth and learning in the health system also need to be developed. Research needs an upgrade, rebalancing funding to include a focus on making use of existing knowledge and applying what is known so that everyone can benefit from research findings.

Change in the three areas I have identified will require a perspective longer than the one-termism that often bedevils policy development. In prevention, for example, the evidence base for what works is still weak in many areas – such as how to refocus policy to address the impact of broader “social determinants” on health.

In its first term, the government needs to build the evidence base through well-structured pilots, setting the second term agenda of implementing what is shown to work. Most of what needs to be done is not “big bang” reform but small-scale change that shows what works or makes marginal shifts in policy settings to position the health system better for the future.

Although Health Minister Peter Dutton has been quoted saying he fears for the sustainability of the health system with the increasing prevalence of dementia and diabetes, “sustainability panic” doesn’t provide a good frame for policy consideration.

The impact of ageing is not going to swamp the system. Image from shutterstock.com

The pressures on the health system are impacting slowly and incrementally. The impact of ageing is not going to swamp the health system overnight: we face a grey glacier not a silver tsunami.

Big announcements aren’t the answer. The health system needs a long-term plan, setting out what will happen, what we don’t know and how to fill the evidence gaps. System reform should also build on the work that has gone before, perhaps picking up the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission’s recommendations that the previous government mostly swept under the carpet.

Policy change should be undertaken carefully and incrementally. We need to avoid quick fix, sound-bite policies. Shifting costs to poor consumers should be avoided. We need to build on the policies that have given Australia a health system that is below comparable nations in cost per head and above them in life expectancy.