Published at The Conversation, Monday 29 September

The baby boomers are growing old and in the next 25 years the number of Australians who die each year will double. People want to die comfortably at home, supported by family and friends and effective services.

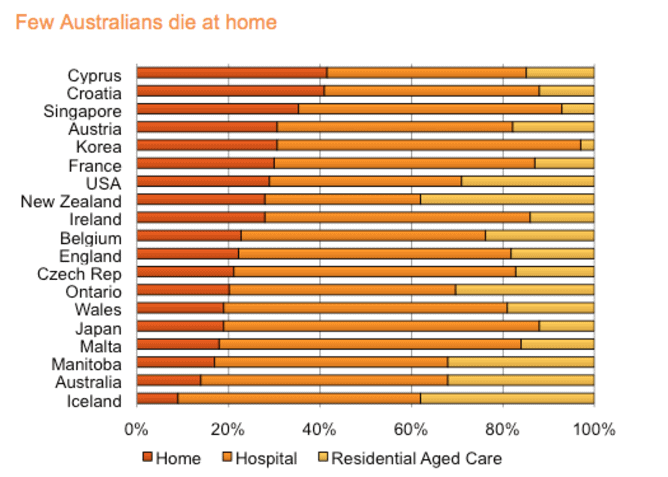

But more than half of Australians die in hospital and about a third die in residential care. Sometimes they have impersonal, lingering and lonely deaths; many feel disempowered.

Grattan Institute’s new report, Dying Well, released today, sets out how we can improve the quality of dying in Australia. With an investment of A$237 million, we can double the number of people who are supported to die at home – and the same amount could be released from institutional care spending to pay for it.

Institutionalised death

Over the past 100 years, home deaths have declined and hospital and residential care deaths have increased. Even over the past decade, the hospitalisation rate for those aged over 85 increased by 35% for women and 48% for men. Hospitals and residential care – nursing homes – are the least preferred places to die.

Around 70% of Australians want to die at home, yet only 14% do so. People die at home at twice this rate in New Zealand, the United States, Ireland and France, partly because of the differences in support systems.

Adapted from Broad et al 2013.

Deaths for younger people are now rare; about two-thirds of Australians die between the ages of 75 and 95. These days older people are more likely to know when they are going to die in the relatively near future. But we are not taking the opportunity to help people plan to die well.

When asked, most people have clear preferences for the care they want at the end of their life. But rarely do we have open, systematic conversations that lead to effective end-of-life care plans. Most people do not discuss the support they would like as they die.

Dying at home puts pressure on families and informal care, and this pressure is exacerbated in the absence of good support systems. With social change and increased population ageing, the carer ratio – the number of people who need a carer to the number of people who have one – is falling. Already, a significant proportion of dying people do not have a carer.

The result of these problems is that many experience a disconnected, confusing and distressing array of services, interventions and relationships with health professionals. They also end up dying in the very places they expressed a preference not to.

Towards better deaths

A good death gives people dignity, choice and support to address their physical, personal, psychological, social and spiritual needs. As we outline in Dying Well, this would happen more often with three reforms.

First, we need more public discussions about the limits of health care as death approaches, and what we want for end-of-life care. Public education campaigns are a well-established way of promoting change. A national public education campaign would focus on encouraging people to discuss their preferences and choices for end-of-life care with health professionals, including GPs.

Second, individuals need to plan better to ensure that our desires for the end of life are met. Too often we have not appointed someone we trust to make health care decisions when we are unable to, nor set out our wishes for treatment when there is little chance of recovery.

We need trigger points as we get older to remind us to have a conversation about what we want in terms of end-of-life care. Potential trigger points are:

- over-75 health assessments

- entry to a residential aged care facility

- hospital in-patients assessments that conclude the person is likely to die in the next 12 months.

Third, services for those dying of chronic illness, such as cancer or heart disease need to shift their focus from institutional care and often unrealistic attempts at cures to supporting people’s preference to die at home and in home-like settings, in less pain.

The burden on carers can be reduced by providing more coordinated home care services for dying people including access to personal care and practical support, and symptom management for pain and nausea. Such services will become increasingly important as the number of informal carers declines as a result of more women working and smaller family size, among other changes.

Greater investment

If more people are to die at home, investment in community-based support is needed. Doubling the number of people who are supported to die at home will cost A$237 million a year. However, about the same amount could be released from institutional care spending to pay for it.

Contrary to widespread assumptions about the cost of end-of-life care, only about A$5bn a year – about 5% of the health budget – is spent on the last year of life. Admittedly this spending is only for about 1% of the population who die each year, so the cost per person is high. But less than A$100 million is spent on helping people to die at home. A change in focus will be cost neutral, and help more people to die well.

When death comes for each of us, we want to die comfortably, in surroundings we choose. We need the courage to promote mature discussions about a topic we may dislike but cannot avoid if we are to have better deaths in Australia.