New political donations data show who’s funding whom

by Kate Griffiths, Jessica Geraghty

As federal parliament reconvenes this week, the pre-election buzz is palpable. When will the election be called? Which policies are on the table? And who’s backing whom in this election campaign?

While the first two questions are yet to be answered, we ought to have a better sense of the third with the release of the annual political donations data.

There’s plenty to unpick in the new data but there’s one glaring problem: we are only just now learning about donations made in 2023–24. Australians are left in the dark about who is donating right now.

Here’s what happened in 2023–24

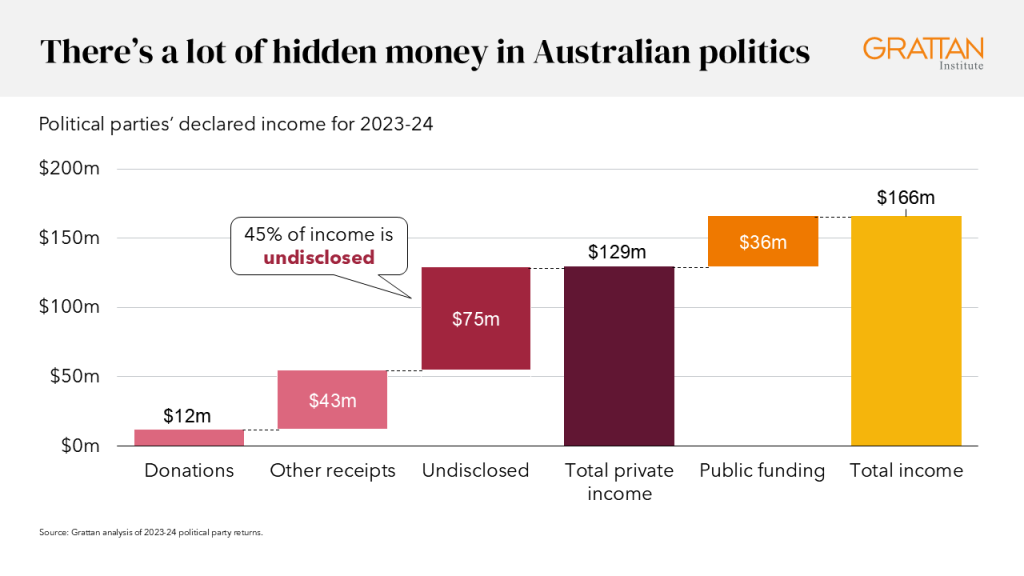

In 2023–24, Australia’s political parties collectively raised $166 million, with most of the money (85%) flowing to the major parties. In federal election years the totals can be more than double this, and donations at the past two federal elections have been heavily dominated by Clive Palmer giving to his own party (in 2019 and 2022).

The Coalition raised $74 million in 2023–24, with Labor not far behind on $68 million. The Greens were a distant third, with $17 million. Independents collectively declared just $2 million. In the lead-up to the last federal election, Labor raised $124 million, and the Coalition raised $115 million, so we would expect the major parties are raising much more right now.

The big donors

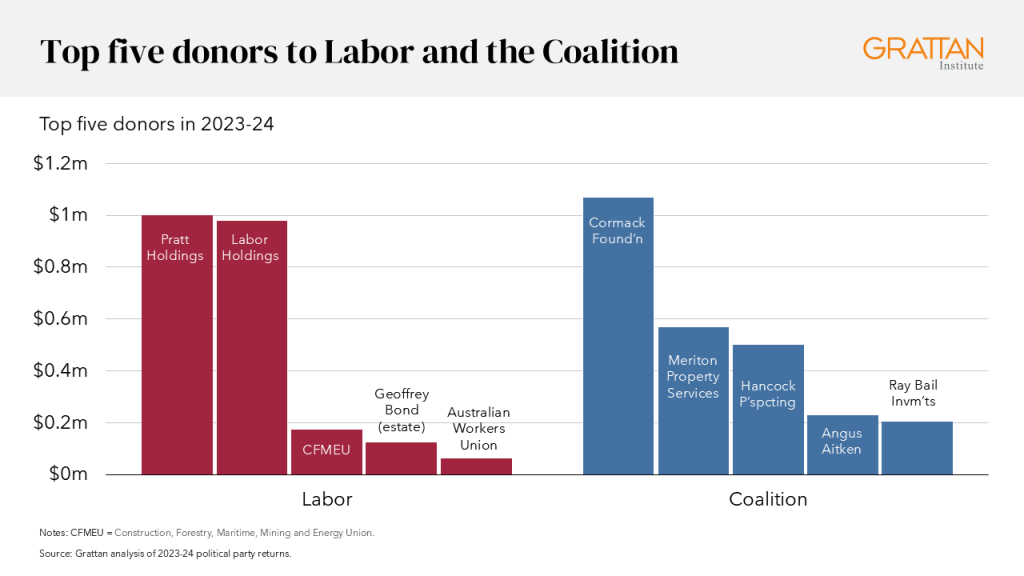

A few big donors dominate the $12 million in donations to political parties that are on the public record.

Billionaire Anthony Pratt donated $1 million to Labor (through Pratt Holdings), while the Coalition was supported by billionaires Harry Triguboff (through Meriton Property Services) and Gina Rinehart (Hancock Prospecting), to the tune of around half a million dollars each. Both Labor and the Coalition also received major donations from their investment arms (Labor Holdings and Cormack Foundation, respectively).

Other major donations included $575,000 to the Greens from Duncan Turpie, a longtime backer of the party; $474,000 from Climate 200 backing several independents (mainly Zoe Daniel and Monique Ryan); and $360,000 to the Greens from Lisa Barlow’s conservation trust.

The big donor missing here is Clive Palmer. The size of his donations – $117 million in 2022 and $84 million in 2019 – blow everyone else out of the water, but he tends only to donate in election years. We won’t know how much he’s spending on the current election campaign until February 2026.

What needs to change

Money matters because it helps spread political messages far and wide. But when political parties are highly dependent on a small number of powerful individuals, businesses, and unions, to fund their campaigns, this dependence creates enormous risks of private influence over decision-making in the public interest.

That’s why Australians need to know – in real time – who’s funding election campaigns.

Under the current rules, it takes at least seven months and sometimes up to 19 months for a large federal donation to be made public. Yet at state level, donations must be made public within a month during election campaigns, and within six months at other times.

Introducing quicker disclosure requirements at the federal level would mean Australians would know who’s donating while policy issues – and elections – are still “live”.

The donations disclosure threshold should also be lowered to give Australians better visibility of substantial donors. In 2023–24, declared donations made up only 7% of political parties’ total income. There are other sources of income on the public record (including public funding), but about 45% of party income remains hidden because the disclosure threshold is so high.

There is no exact science to choosing a threshold, but the current level of $16,900 is well above the amount an ordinary Australian could afford to contribute to a political cause.

This high threshold is made much worse by the fact that political parties are not required to aggregate multiple donations from the same donor. That means, for example, one donor could make many donations of $15,000, but because each is below the threshold, the party doesn’t need to declare them. The donor is expected to declare themselves to the Australian Electoral Commission, but this is almost impossible to police.

The federal government has a bill before the Senate that would reduce the donations disclosure threshold to $1,000, and make release of donations data more timely. These changes would substantially improve transparency around money in politics. But the bill also includes more complex reforms that may stall the progress of these transparency measures.

Better and more timely information on political donations is urgently needed as a public check on the influence of money in politics.

Let’s hope this is the last election Australians are left in the dark on who funds our political parties.