Novel ideas: the books Scott Morrison should read this summer

by Danielle Wood, Eloise Shepherd, Anika Stobart

As 2020 drew to a close, Scott Morrison may have looked towards 2021 with a sense of optimism. But Covid-19 had other ideas, and Australia’s attention was soon fixed upon combating the deadly new Delta strain. This year has been marked by multi-state lockdowns, border closures and a fraught vaccination rollout, leaving the population exhausted. But as Australia nervously enters a new phase of normalcy (Omicron-permitting), there remain policy issues on the other side of the roadmap that demand attention.

Boosting educational standards, reconciling our history with our First Nations people and our unhealthy reliance on a small handful of big tech firms areon the government’s priority list. Other issues, including conserving Australia’s environment, and addressing poverty and entrenched economic inequality, are worthy of any vision to “build back better”.

These books tackle these big issues and provide constructive ideas for the road ahead.

On Money, by Rick Morton

Hachette

Rick Morton has carved out an impressive career in an industry that he describes as an elite cultural institution. Having grown up in poverty, Morton knows first-hand that the entry price for opportunity is not equal for everyone. For some like Morton – who grew up with nothing and had nothing to fall back on – every day is a fight for survival, and he describes the “cognitive tax” that this imposes on the nation’s poorest. Often one financial mishap, traumatic event or bad decision can kickstart a lifetime of cascading consequences; a reality that isn’t always understood by those born with privilege, who are afforded the “time and space” that money provides.

These consequences, Morton explains, place heavy burdens on tired bodies and on impoverished brains. He writes fondly of his weary mother who, having spent a life doing constant mental arithmetic, of “lifting and scraping and effort, effort, effort”, is old beyond her 60 years. Extrapolate this weariness across the 700,000 Australians that the Productivity Commission estimates live in persistent disadvantage and it’s clear that the lifelong physical and mental health costs of economic inequality demand urgent intervention.

Morton identifies the tangle of welfare systems and institutions, of political pledges and punishments, that has created an environment where attitudes towards people living in poverty have shifted towards using money as a measure of moral character and worth.

On Money meticulously describes the implications of financial hardship and the policies that exacerbate it through the eyes of someone who has lived it. It’s a piercing and personal piece, a deeper look at how his experiences as a child (recounted in his brilliant memoir One Hundred Years of Dirt) shaped his relationship with money. It perfectly explores how a life spent choosing from a “restricted buffet” can cause damage across generations.

Rick Morton is a national treasure and On Money is a shining gem of insight into systemic inequality. We are all richer for his work.

She Is Haunted, by Paige Clark

Allen & Unwin

Melbourne’s Paige Clark has burst on to the literary scene with her debut collection of 18 short stories. She Is Haunted is an ethereal work that deftly explores relationships, loss and grief. Clark, who is third-generation Chinese American and first-generation Australian, weaves her own experience of the transnational identity via excruciatingly relatable characters. Each story is written with a piercing dry wit, entwined with pathos-laden gut punches. Most of Clark’s protagonists are women, and in a year when the voices of Australian women were given prominence, She Is Haunted is a timely, refreshing and deeply intimate experience.

Clark’s writing is spare but her attention to the minutiae of life is evocative. She has interwoven the mystical and the mundane, depicting the surreal and the ordinary throughout the lives of her characters, who are all fallible but mostly sympathetic. A widowed woman self-soothes with clothes left behind, transforming physically into her late husband to avoid grieving his loss. A Woman in Love is split from her beloved and elderly dog after her marriage ends. High-jinks ensue as she embarks on a “dog-napping” escapade so she can clone the toothless chihuahua, but we are privy to a past of devastating genetic testing results and the comfort the dog brought. A woman and her partner voluntarily undergo removal of their left frontal cortex to withstand oppressive heat wrought by a heating planet: indeed, menacing hints of climate change stalk many of Clark’s stories.

She Is Haunted is a like a cosmic prism through which readers can view life and death. Spirits and the spiritual haunt carefully crafted vignettes, windows into souls that are grieving, bargaining, lost, jealous. While loss and death are constant throughout the book, Clark’s nimble prose keeps readers curious, with surprising deviations crafted within each chapter.

Paige Clark has created a dazzling debut. We look forward to what’s in store from this talented young Australian author.

System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot, by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy Weinstein

It’s been a big year for big tech. While negotiating new media laws, Facebook banned Australian news sites, the ban reaching well beyond news to government and not-for-profit pages. Anti-vaxxers used the internet to spread health misinformation. And the world was confronted with the terrifying power of social media used to mobilise the attack on the US Capitol building.

Considering these incidents, governments around the world face a significant challenge: how to regulate an industry that runs faster than the rules can be made.

While many books have tried to capture the sisyphean task facing policymakers in regulating big tech, few have succeeded as well as System Error.

The three authors outline how the often-libertarian beliefs of technology professionals lead to unregulated technology markets that come into conflict with democratic ideals. Many of these issues stem from an optimisation mindset, built into computer programmers and the startup elite at university. Technologists see their job as solving the problem in the most efficient way. But siloed development means no one’s asking if it’s a problem worth solving, let alone if there are negative side-effects.

Where some books take a “democracy good, big tech bad” approach, it’s the nuance and complexity of System Error that holds it above other offerings. The book explores the all-pervasive nature of big tech that touches every aspect of the democratic process. Lobbying against privacy and media laws, the impact of the gig economy and the increasing monopolies of the big five are just some examples given here. But the book also shares the lessons big tech can teach governments about agility in times of crisis – including how to make a Covid-tracing app that people might use.

Although System Error is written from a US perspective, the book highlights the need for a global approach to regulating big tech. After all, these companies may be based in the US but their effects are felt worldwide.

Australia might be well placed to test some of the recommendations, as a middle-power, English-speaking country relying on globalisation. In fact, Australia’s media content laws trying to extract revenue from Google and Facebook are exactly that, on a small scale. The authors also point out that few policymakers have technological backgrounds. As a starting point, Australia needs more digital experts in parliament and the public service.

A book on technological policy might sound like a dry read: this one’s not. The authors spin a compelling argument that has implications for all of us. You might think twice the next time you click “like”.

The School, by Brendan James Murray

Pan Macmillan

In the opening lines of The School, Brendan James Murray observes: “Schools are haunted. Ghost children flitter and lurk and whisper … no latest initiative, no departmental ‘best practice’ will exorcise them.”

Politicians and policymakers talk a lot about schools but how well do most of us know what goes on inside them? Are we brave enough to look beyond the facade to the tangled web of social expectations, bureaucratic improvement plans and complicated human currents that course through the classrooms and corridors, spilling out into the playground?

The School is a powerful story about a notional year in the life of a teacher. Murray draws on his experience as an English and literature teacher at “The School”, a modest suburban secondary school on the edge of Port Phillip Bay, where he happened to spend his own days as a student.

As Murray warns us at the outset: “You will find these pages cluttered with souls jostling for your attention. That is the reality of teaching.” These souls are vividly rendered, their voices urgent.

Murray writes compellingly about the burden of obligation – and the genuine gratitude – he feels towards his students, and the excitement of shepherding them towards new understandings. Nobody could read this account without reflecting on how profound an impact a good teacher can have on the lives of students.

But this is no sentimental yarn. Murray reveals his frustration at the lack of resources at The School to tackle sometimes shocking levels of adolescent illiteracy, the heavy toll on young lives of poor physical and mental health, the radiating legacy of family trauma, the ease with which social cruelty and physical violence can be inflicted in the schoolyard, and the seeming indifference of a small handful of colleagues.

But Murray resists the temptation to lay blame at the feet of the usual cast of villains: cynical politicians, heartless bureaucrats, neglectful parents, a few bad teachers or troubled students. It is refreshing to read an account that acknowledges that these challenges are difficult and defy simple explanation.

It is impossible to read this book without feeling a deep sense of obligation – and motivation – to keep asking what more, or what else, can we do to honour the ghost children who walk the grounds of The School.

Truth-Telling, by Henry Reynolds

NewSouth

The Uluru statement from the heart speaks with the powerfully united voice of First Nations Australians and calls on all Australians to tell the truth about our history.

It is nearly 250 years since the arrival of the British, and yet in many ways we are still resisting the truth of our past.

In his new book Henry Reynolds makes an important contribution to this truth-telling process, drawing on his long career as an Australian historian.

The book is a piece of revisionist history that begins in 1788, and carefully steps through the legal concepts of sovereignty and property law within the context of the international law at the time, laying bare how the “scale of the expropriation was without precedent”.

Reynolds presents a wealth of evidence, including letters from the colonial office in London – which oversaw the colonial affairs of Britain – that demonstrates how the colonists’ violence and legal overreach went beyond what even the colonial office deemed acceptable.

Documents show that the British government had acknowledged that First Nations Australians were proprietors. Yet this did not stop the land theft by colonists in Australia.

Britain claimed the benefits of the sovereignty it asserted over the land, first in New South Wales, “which would have been found illegitimate in international law”. But the British did not always uphold their responsibility that came with that – which was to provide protection from harm to all sovereign subjects, including Indigenous Australians.

Instead, Reynolds argues that the British “turned their back on the tradition of treaty-making fully conscious of what they were doing”. The British government had created a situation where “tension could only be relieved by violence”.

A common refrain about Australia’s past is that colonisation, while brutal, “was acceptable behaviour at the time”. Truth-Telling demands that Australians face up to the real truth of our past. Only then can we genuinely engage with the Uluru statement from the heart and move forward firmly and constructively.

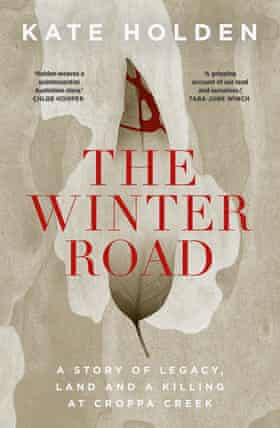

The Winter Road, by Kate Holden

Black Inc Books

On a stretch of dirt road in outback NSW, 78-year-old farmer Ian Turnbull raised his hunting rifle and aimed. The first shot knocked Glen Turner, a state environmental officer, to one knee.

As dusk fell on Croppa Creek, Turner and his workmate dived behind their ute, pleading with Turnbull to no avail. In desperation, Turner turned to run. Once more, a shot echoed over the cleared farmland, this time striking Turner in the back. “I’m going home to wait for the police,” the elderly farmer said as he stepped into his ute. He drove off, leaving Turner dead in the arms of his partner.

Australia’s history with our land – the clash between farmers wanting to clear and work it, and those seeking to preserve it – runs deep.

Equal parts crime and history, The Winter Road is a gripping tale of legacy, land and the killing at Croppa Creek.

Using the July 2014 murder of Glen Turner as a launching point, Kate Holden dives into the events that led to the shooting and the history that preceded it. The tension between Turner, a government official intent on enforcing environmental regulations, and Turnbull, a farmer who believes in the right to treat his property as he wishes, speaks to broad ideas of ownership and government, of exploitation and preservation.

The result is a meticulously researched look at the continuing tug of war between land ownership, inheritance, enforcement and preservation efforts in Australia. The Winter Road raises fundamental questions about the give-and-take relationship Australians have with the land – from First Nations ideals of continuity and preservation to European notions of taming the land through work. It highlights the complex nature of the laws that govern land and the dangers that those tasked with enforcing protection can face.

By deftly explaining the history behind invasion, settlement and the traditions of preservation and farming, Holden tells a uniquely Australian tale. It captures deep and difficult questions about exploitation of the land we live on, and how it relates to our history, laws and society.

Eloise Shepherd

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO