Published by Tax and Transfer Policy Blog, Monday 5 August

At the heart of the debate over higher compulsory superannuation sit big trade-offs that are too rarely acknowledged. Boosting retirement incomes inevitably comes at a cost: either people have lower living standards while they’re working; or governments give up more revenue for super tax breaks; or taxpayers pay more for pensions.

Grattan Institute’s recent analysis examined some of these trade-offs. It showed that higher compulsory super wouldn’t be in the interests of many working Australians. It would mean middle-income workers giving up wages of up to 2.5 per cent while working, in exchange for less than a 1 per cent boost to their retirement incomes.

Just about all of the extra income from a higher super balance at retirement would be offset by lower pension payments, due to the pension assets test. And pension payments themselves would also be lower under a 12 per cent superannuation regime, because pension payments are benchmarked to wages, which would be lower if employers had to put more into super.

Taken together, we find that lifting compulsory super from 9.5 per cent of wages to 12 per cent would make the typical worker up to $30,000 poorer over their lifetimes.

Andrew Podger takes issue with our analysis. He argues that our work demonstrates a different problem: that the pension assets test is too harsh. Under changes passed in 2017, retirees currently lose $3 of pension payments every fortnight for every $1,000 of assets they own above the asset threshold. Andrew argues that a better-designed pension means test would see higher compulsory super contributions boost workers’ lifetime earnings.

Andrew is right to identify the assets test as a problem. Our 2018 Money in retirement report found that recent changes to tighten the Age Pension assets test taper have gone too far, excessively penalising people who save more for their retirement. That’s why we recommended reducing the withdrawal rate of pension benefits to $2.25 a fortnight for every $1,000 in assets.

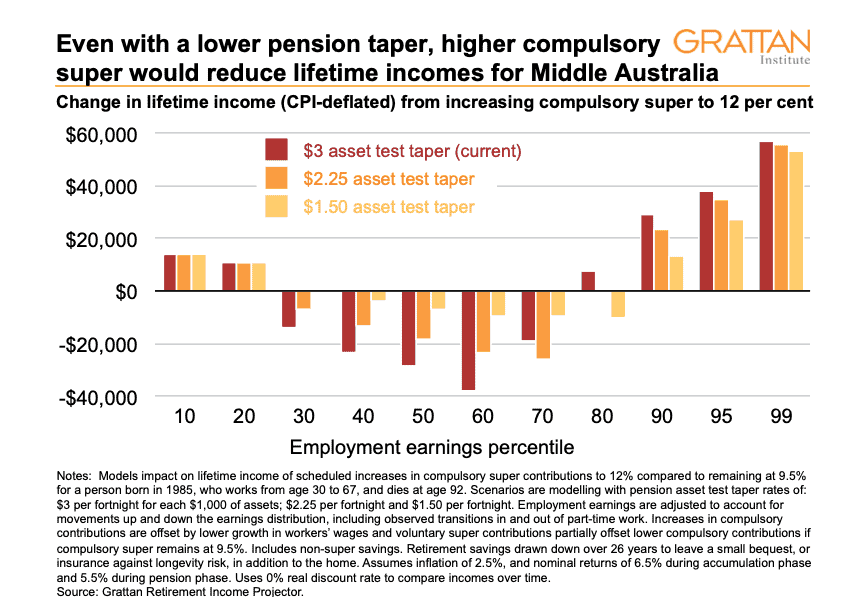

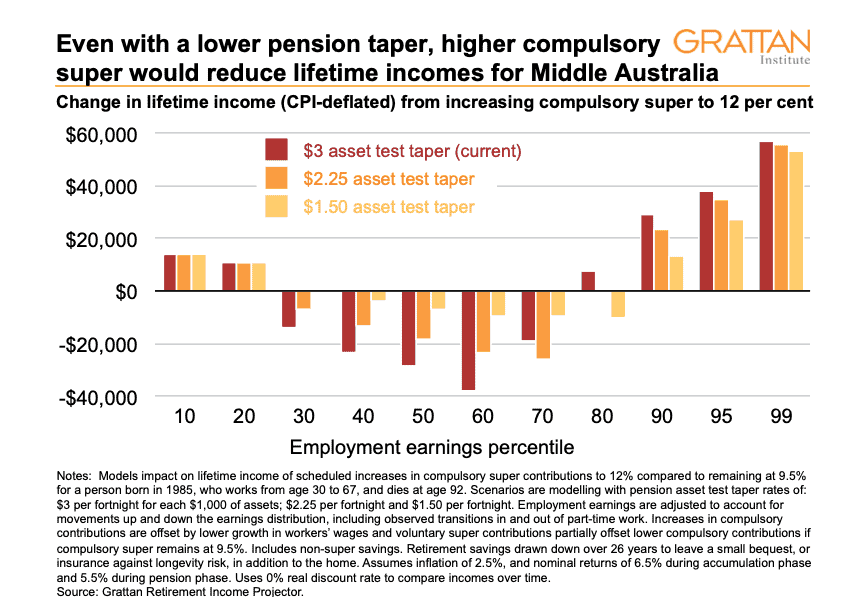

Yet even with a less stringent assets test, higher compulsory super contributions would result in middle-income workers going backwards.

For example, were the pension asset test taper relaxed to $2.25 a fortnight as we recommended, 12 per cent compulsory super would leave middle-income workers $18,000 worse off over their lifetimes (see Figure 1). Under an even more generous $1.50 taper rate, middle-income Australians would still be $7,000 worse off over their lifetimes. A single unified means test might be better still, but it would likely cost the budget even more to implement lest many pensioners today be left worse off.

So, yes, reducing the withdrawal rate of pension benefits would help low- and middle-income workers’ retirement incomes. But doing so would not make an increase in compulsory super a good idea.

Figure 1

And such changes to the pension assets test are not costless. A taper rate of $2.25 a fortnight would cost the budget $750 million a year. Returning to a $1.50 a fortnight taper would cost the budget $1.5 billion a year. And a more generous pension means test would reduce the already meagre pension savings to the budget arising from higher compulsory super.

Andrew Podger also writes that ‘What would really help is if Grattan articulated what it considers to be the objective of the retirement incomes system and focused its analysis on whether increasing the Superannuation Guarantee would or would not help to achieve that objective, and at what cost’.

This is baffling: our Money in retirement report was all about what the objective of the retirement incomes system should be, and how policy should be adjusted to achieve it. Indeed, Andrew agrees with us on what the objectives should be: to ensure no Australian lives in poverty in retirement, and to maintain Australians’ pre-retirement living standards.

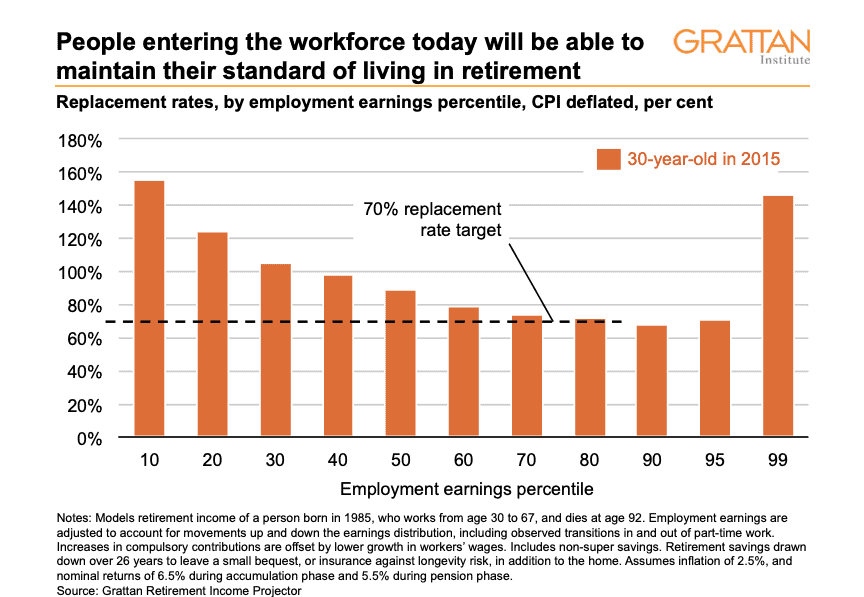

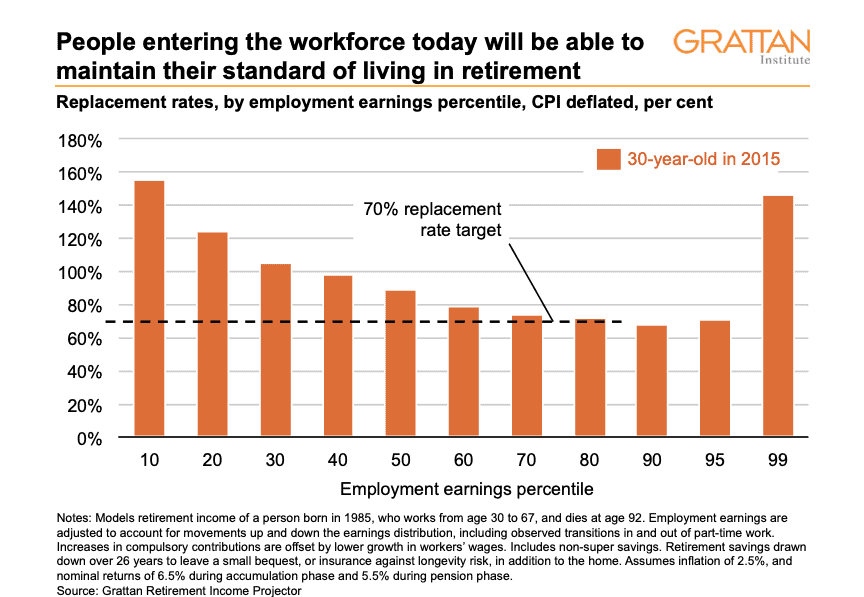

Our 142-page report showed there’s no need to increase compulsory super to meet that benchmark. In fact, most Australians can already look forward to a better living standard in retirement than they have while working. In other words, compulsory super of 9.5 per cent is doing its job.

Grattan’s latest modelling shows the median worker today can expect a retirement income of at least 89 per cent of their pre-retirement income – well above the 70 per cent benchmark used by the OECD and others, and more than enough to maintain pre-retirement living standards (see Figure 2). Many low-income Australians will get a pay rise when they retire, through a combination of the Age Pension and their compulsory superannuation savings.

Figure 2

Andrew Podger describes our position as ‘extreme’. He’s entitled to his view, but the facts are that our modelling accords with that published previously by the Australian Treasury, and produces similar replacement rates in retirement to those of actuarial firm Rice Warner.

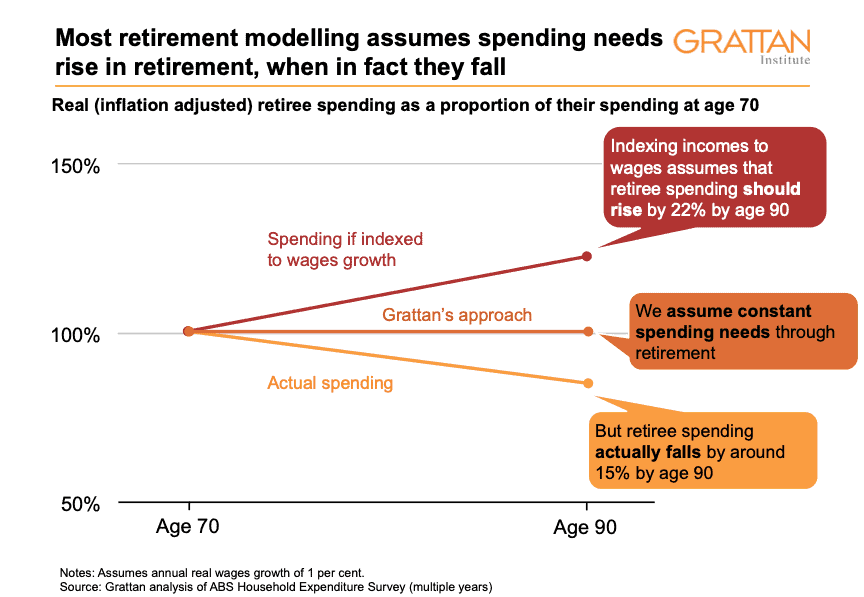

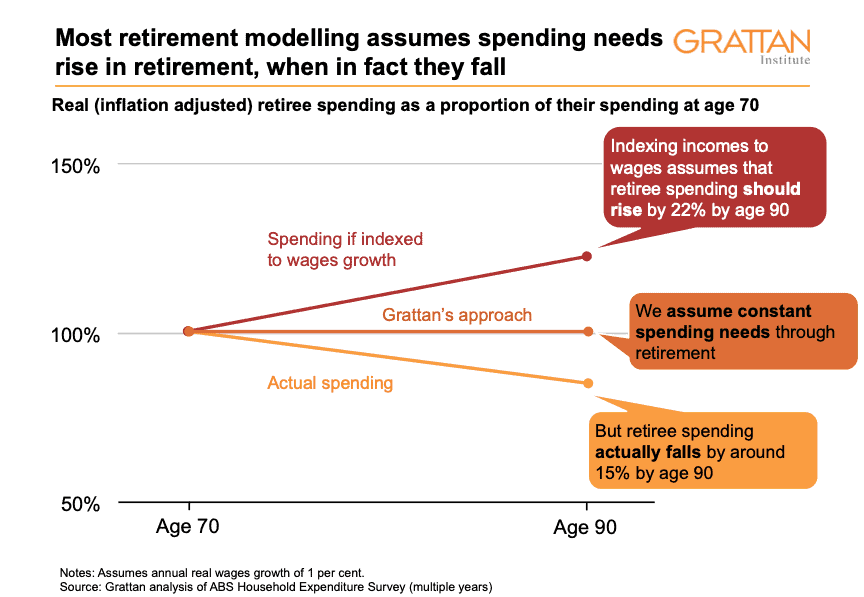

In contrast, other modelling, such as the committee research Andrew cites, concludes that retirement incomes are inadequate because it assumes that retirement incomes should keep pace with the wages of workers, rather than just keeping pace with inflation. The problem with that approach is that it implicitly assumes that a retiree needs to spend 22 per cent more at age 90 than at age 70, even after accounting for inflation. That doesn’t sound right, because it’s not right. Our research shows that people’s spending typically falls by 15 per cent over those 20 years (see Figure 3). Retirement modelling should do its best to reflect reality. Too much Australian modelling remains wedded to out-dated assumptions that fail to do so.

Figure 3

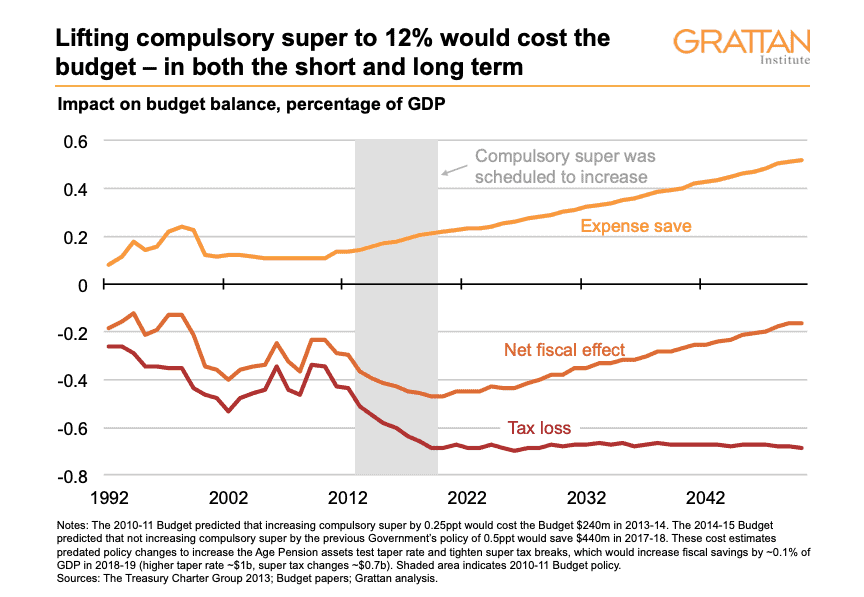

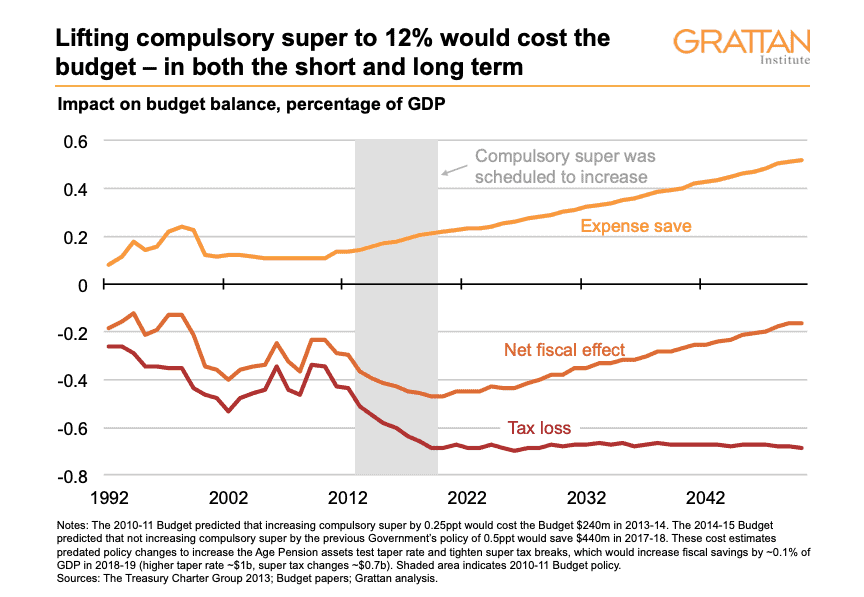

Which brings us to the next problem with higher compulsory super: it would exacerbate the budgetary costs of an ageing population.

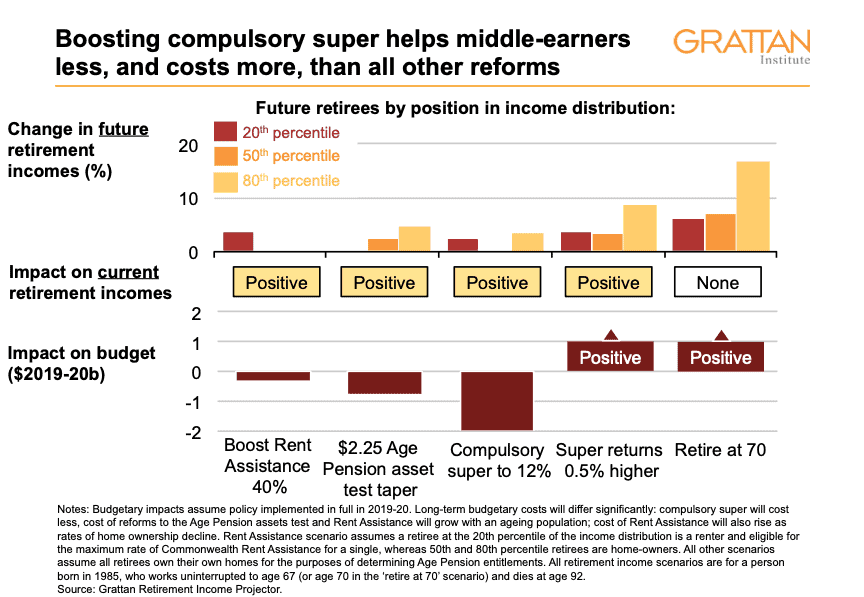

Lifting compulsory super to 12 per cent of wages would cost the federal budget $2.5 billion a year. These budgetary estimates are not based on some theoretical treatment of tax breaks; they are based on how Treasury expected actual changes in compulsory super to hit previous budgets. It’s true that compulsory super today has lowered pension spending. But Treasury projections have also shown that the tax breaks from 12 per cent compulsory super would dwarf any budget savings on the age pension as far out as 2060 (see Figure 4).

The budgetary impacts of higher compulsory super are unmistakable. Even the Henry tax review concluded higher compulsory super would cost the budget in the long term – when it recommended against raising compulsory super beyond 9 per cent.

Figure 4

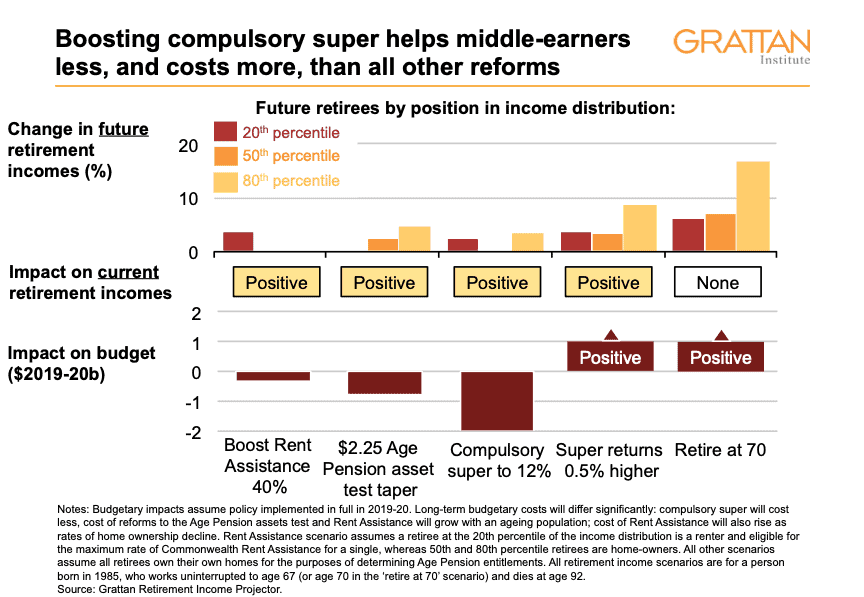

Even if governments wanted to boost retirement incomes, the planned increase in compulsory super contributions to 12 per cent appears the worst way to get there. Our work shows that raising compulsory super to 12 per cent would reduce wages today and do little to boost the retirement incomes of many low- and middle-income workers tomorrow. It would also lead to lower pensions for both current and future retirees.

More importantly, higher super wouldn’t tackle the real challenges facing our retirement incomes system: the pensions assets test taper is too harsh; and retirees who rent are at severe risk of poverty because Commonwealth Rent Assistance is inadequate. (The latter is a growing problem, because home ownership is falling fast and therefore more retirees will rent in future.)

Grattan has recommended policy changes to address both of these challenges.

For example, relaxing the Age Pension asset test taper would do more than raising compulsory super to 12 per cent to increase retirement incomes for people earning up to 1.5 times average earnings ($120,000 a year) (see Figure 5). And it would cost the budget less than a third as much ($750 million a year compared to $2.5 billion a year).

And Boosting Commonwealth Rent Assistance by 40 per cent – or roughly $1,400 a year for singles – would lift out of poverty many retirees who rent. The cost would be $1.2 billion a year.

Figure 5

The tragedy of higher compulsory super is that it doesn’t address these challenges, while its budgetary costs would make it harder for governments to adopt other policies that would.

Retirement incomes policies should be assessed on their impacts against the objectives of the system. That’s why the Productivity Commission recommended an independent inquiry into the role of compulsory super in our retirement incomes system before compulsory super is lifted, a recommendation the Government has embraced.

Grattan’s work on retirement incomes has been dedicated to answering precisely those questions. And a clear-headed assessment shows that raising compulsory super is bad for workers, pensioners and taxpayers.