Published in Croakey, 24 July 2020

The skills and experience that members bring to the board table are critical to the success or failure of an organisation.

The Not-For-Profit Governance Principles, produced by the Australian Institute for Company Directors (AICD), highlight the importance of not-for-profit organisations reflecting on the skills their boards need to lead a well-functioning organisation.

The example skills matrix in the AICD Principles is a minimalist matrix and the Principles recognise that some organisations will ask directors to assess their level of proficiency against the set criteria.

This is the approach that Eastern Melbourne Primary Health Network (EMPHN) has adopted and involves a three-stage approach.

1. A skills, experience and diversity matrix

It is time that the tired old language of ‘skills matrix’ is updated to highlight the importance of board diversity and experience, as well as skills.

A skills matrix often encourages a focus on narrow, generic skills (finance, risk, legal) arrayed as columns.

At EMPHN we recognised that, although these technical skills are important, we needed to also consider where board members gained their skills and experience.

As a primary care network, we need to ensure that the board had members with deep contemporary understanding and experience of primary care. The EMPHN matrix also highlights qualifications (legal, accounting), professional memberships, as well as skills and experience.

Most boards in the not-for-profit sector – and even in listed companies – have addressed gender diversity with women making up at least half the board and committee membership.Other aspects of diversity (age, culturally and linguistically diverse background, Indigenous identification) are not so well addressed.

At EMPHN we are still working to fully address diversity, but incorporating relevant dimensions in the matrix makes it transparent, front of mind when considering composition and supports discussion of commitment to diversity that is broadly representative of the community being served.

Importantly, no board member is appointed because of one skill, experience, or diversity criterion alone, to avoid tokenism and to ensure richness in appointment.

2. Moving beyond a dichotomy

As hinted in the Governance Principles, skills and experience should no longer be measured as a dichotomy, boards need to consider how much depth of experience they need.

Boards need to think about what experience is needed now and into the future and ensure alignment with the organisation’s strategy.

Board members are often asked to self-certify whether they have the relevant skills and experience in each column of the matrix. Board members have little guidance about when it is appropriate for them to tick the relevant column, or what rank to give themselves.

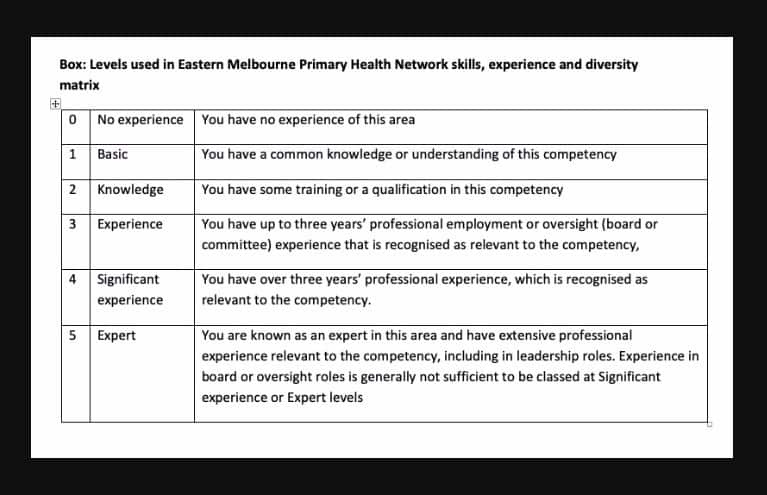

At EMPHN we addressed issues of inter-rater reliability through a guide for assigning rankings (see box), and this also highlighted that, to justify a higher ranking, one needed to have deep work experience in an area, rather than governance experience alone.

3. Identifying the skills required

Tallying the number of ticks or the total score for a column of the matrix is not enough.

At EMPHN we identified the skills required with a survey of board members asking them what was the minimum number of people the board needed in each of the columns of the matrix to effect its business and achieve its strategy, and in particular, what was the minimum level we needed at the ‘experienced’, ‘significantly experienced’ and ‘expert’ levels (ratings 3, 4, and 5).

Sometimes one person with high level skills and experience is enough, but in other cases a board might be looking for more depth in a particular area.

In the EMPHN example, we wanted to ensure that we had more than one person with skills and experience in general practice and primary care, and that they practice in the area we serve.

4. Bringing it all together

The new, more elaborated, matrix helped the board in its 2019 round of board appointments.

It guided the brief to the recruitment consultant, and the relevant board committee, to help refine what was missing from the current board make up.

It also helped board members see where experience and diversity was lagging so helped to avoid complacency and staying with the status quo. As a result the board identified the need to ensure that it had more members who lived and worked in the area served by EMPHN, and that we had appropriate depth of talent in key areas, rather than relying on a composition which had a number of members with ‘basic knowledge/experience’ in an area.

The 2020 round of consideration is now underway. It involves the same two-process of board members self-reporting their own skills and perceptions of what the board as a whole needs.

The next stage is underway: the board chair speaking to each board member to talk about how they ranked themselves, and what they saw as the priorities to ensure we had a board with the appropriate skills, experience and diversity.

The EMPHN approach to a skills, experience and diversity matrix is still evolving. We still have a long way to go in calibrating the scoring system and reflecting on whether the wording of the column headings is right.

We haven’t worked out how we incorporate – and measure – commitment to the values of the organisation and its purpose, and this is particularly important as people with generic skills – say in finance – need also to be able to apply those in a way which is consistent with the ethos of the organisation.

The development of the EMPHN matrix arose from work done as part of the Victorian review of safety and quality a couple of years ago led by Stephen Duckett which identified weaknesses in the approach used to select members of Victorian public hospital boards, which that time relied on the narrow dichotomy approach.

This paper was stimulated because of approaches to one of the authors (Stephen Duckett) about what the EMPHN approach to board selection was. These approaches came from another not-for-profit and from a professional association.

Obviously the EMPHN matrix was relevant to neither, but the approach of moving beyond a simplistic skills matrix, with skills measured as a dichotomy, is broadly relevant. The advice given in both cases was to be really clear about what the relevant skills were, and they will be different from industry to industry, and should change over time.

The EMPHN approach encourages us to reflect more carefully on the mix of generic skills, industry experience, and diversity, which will help us make better board decisions. The approach is also transparent and can be shared with stakeholders who want to know more about the Board, its skills, experience and diversity.

The approach is reflective and adaptable, and the importance of this to ensure a Board with experience, skills and diversity that support the current operating environment of a company has been highlighted during the current COVID pandemic.

Governance of not-for-profit is different from governance in for-profit organisations, but it is still important to ensure that boards are appropriately skilled to govern the organisation.

Too often not-for-profit boards import, unthinkingly, practices from for-profit organisations without adapting them to the new environment.

A board with the appropriate mix of generic skills, industry experience, and diversity will lead to better governance, and through that, better outcomes.

Stephen Duckett, Grattan’s Health Program Director, is Chair of the Eastern Melbourne Primary Health Network board, and Nadia Marsh is Company Secretary.