Published at The Conversation, Monday 3 February

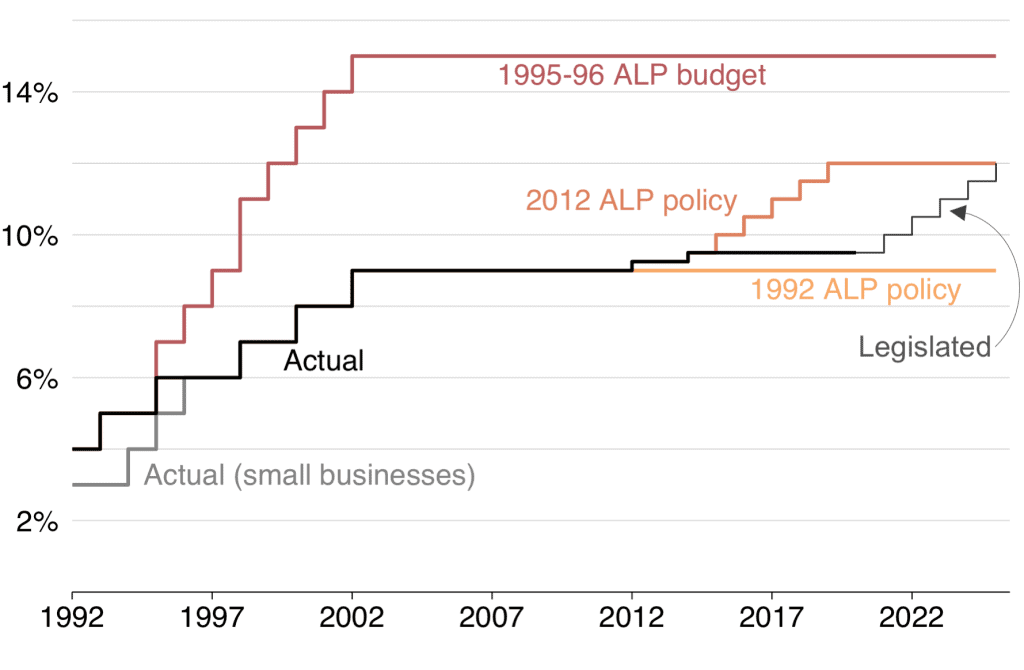

A key question for the government’s retirement incomes review is who ultimately pays for compulsory super contributions, especially since they are set to climb from 9.5% of wages to 12% over the next five years.

Legally, they come from employers, on top of wages. But employers’ contributions have to come from somewhere. Compulsory super was introduced in 1992 with the intention they would come out of funds that would otherwise have been paid out as wage increases.

Modelling by the Treasury, Grattan Institute, and the private sector has long assumed that is what has happened.

But until now there has been scant empirical evidence about who actually pays, and against the backdrop of chronic low wage growth and the imminent increases, the conventional wisdom has come under attack.

Today’s new Grattan Institute study, No free lunch: higher superannuation means lower wages fills the gap.

In an Australian first, it examines detailed data on 80,000 enterprise bargaining agreements over the three decades of compulsory super and concludes that, on average, 80% of each increase in compulsory super has been taken from what would otherwise have been wage increases.

Increases in super comes from wages

In theory, super contributions could come from three sources:

- workers, through lower wage growth

- consumers, through higher prices

- investors, through lower profits.

International studies of similar schemes find that most, if not all, of the cost is borne by workers through lower wage growth.

Our study examined administrative microdata on 80,000 enterprise bargaining agreements filed between 1991 and 2018 sourced from the Workplace Agreements Database maintained by the attorney general’s department.

We compared agreements whose terms spanned legislated increases in compulsory super with those that did not.

Then we estimated what the wage rise in each agreement ought to have been based on detailed information about the agreement, the employer’s industry, and economic conditions at the time it was negotiated.

We were able to see whether there was a systematic difference in wage rises between the agreements that spanned step-up increases in compulsory super and those that did not.

On average 80% of the cost of increased compulsory super contributions was passed on to workers through lower wage rises than would have been expected over the life of those agreements. The long-term impact is likely to have been higher.

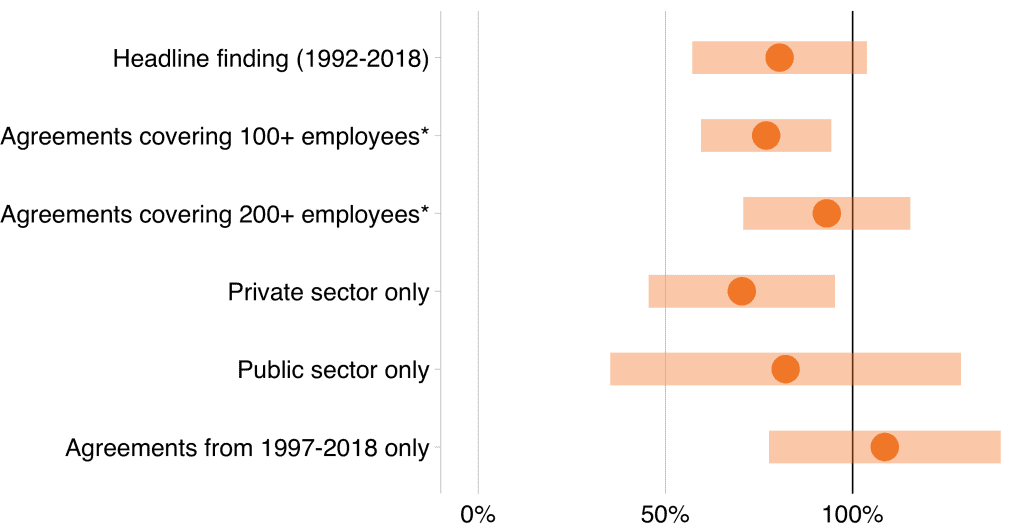

The graph shows the overall finding using data from 1992 to 2018 and also the results from subsets of the including the private or public sectors, big and small firms and the period since 1997.

In each case somewhere between most and all of the cost of super increases was passed through to workers in the form of lower wage increases.

On average, 80% of super increases were at the expense of wages

Source: No free lunch: Higher superannuation means lower wages, Grattan Institute, February 2020

It isn’t only enterprise agreements

Our study looked only at workers on federally-registered enterprise bargaining agreements, around 30% of the workforce. Other workers are also likely to bear the cost of higher super through lower wages.

The Fair Work Commission – the body which sets award wages – has made the link between super increases and award wages explicit, saying that when super goes up, award wages grow more slowly than they otherwise would.

State enterprise agreements are unlikely to differ much from federal agreements, and workers covered by one-on-one arrangements are likely to experience similar trade-offs.

Future super increases are unlikely to be different

It is unlikely the legislated future step ups in compulsory super contributions will be different from the earlier ones.

Although wage growth is slower now than in the past, wages are nevertheless – by all measures – growing by more than 2% a year, offering ample room for employers to wind back wage increases in order to fund each of the five scheduled annual step ups of 0.5% in compulsory super contributions that begin on July 1, 2021.

Source: No free lunch Higher superannuation means lower wages, Grattan Institute, February 2020

In fact, if workers’ bargaining power has fallen recently – as some suggest – employers might feel they can push even more of the cost of higher super onto workers than in the past.

Our analysis shows previous increases in compulsory super came mainly from wages: they took money that would have been handed to workers as wage increases and handed it to fund managers to hold and invest until those workers retired.

The next set of legislated increases are likely to do the same.