Published at The Conversation, Tuesday 3 October

The equation doesn’t look pretty. Traffic congestion costs us billions of dollars each year – so we are told – and population growth is not letting up. When road rage meets large economic costs, it’s little wonder our politicians are desperate to do something.

The trouble is, too often that “something” is a great big new freeway. Building more roads isn’t the best answer, because the roads we have are mostly up to the job – if only we could make better use of them by spreading traffic out beyond the morning and evening peaks.

Instead of focusing on freeways, governments should change the way we pay for urban roads and public transport. To work out how best to do this, the Grattan Institute has looked at several million Google Maps estimates of travel times in Australia’s largest cities. This analysis reveals both the extent of the problem in Sydney and Melbourne and its city-specific characteristics.

For many, the problem is minor

The truth is, for a lot of people, road congestion doesn’t matter much. This is because most people work in a suburb close to where they live.

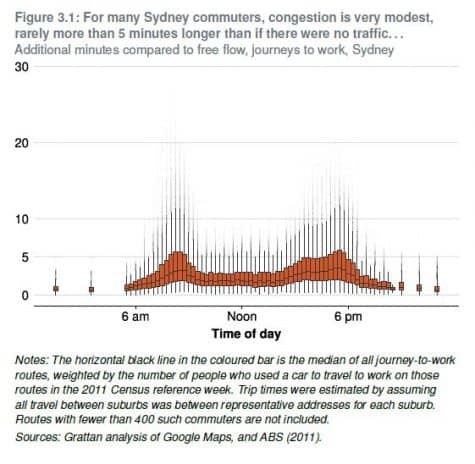

Chart 1 shows congestion delays for Sydney’s 146 most-common commuting trips.

The average delay is small: an average commute at the busiest time of day takes around three minutes longer than the same trip in the middle of the night.

While some commutes are delayed for much longer, it is unusual for trips to take more than ten minutes extra in peak periods.

Congestion is a problem in the CBD and inner suburbs

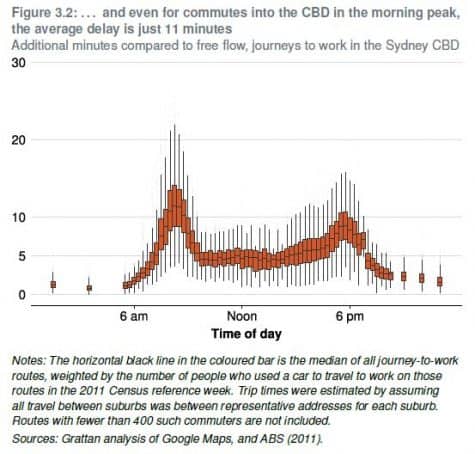

Unsurprisingly, the story is different, and worse, in and around central Sydney and Melbourne. Add in all the trucks and vans, students and tradies, shoppers and people going to appointments, and typical delays for travel on CBD-bound journeys are substantially greater (Chart 2).

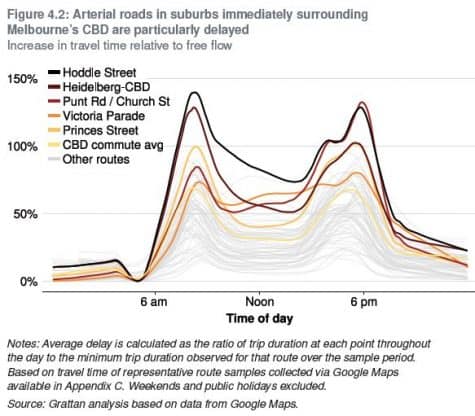

The trends are similar in Melbourne. Travel on CBD-bound journeys is much more delayed than to non-CBD locations.

Chart 3 also shows that delays are noticeably larger in the suburbs that immediately surround Melbourne’s CBD.

Some commutes are frustratingly unpredictable

Most travellers don’t just care about how long a trip usually takes. How long it could take also matters.

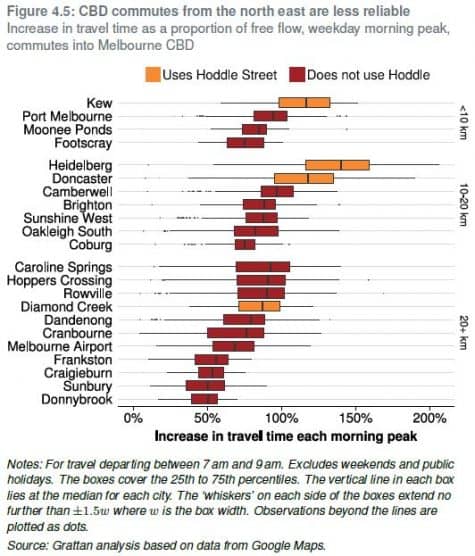

Chart 4 shows that Melbourne’s Eastern Freeway/Hoddle Street corridor has not only some of city’s worst delays, but also some of the least-predictable travel times. Motorists from suburbs to the north-east have to juggle these less-reliable travel times more than those travelling similar distances from other directions.

New roads are not the whole answer

Congestion tends to be worst in the most built-up parts of Sydney and Melbourne, where it would be most costly to construct new roads. This means that even crippling levels of congestion might not justify the construction of astronomically expensive infrastructure.

In any case, new roads often take years to build and can fill up with new traffic of their own.

New roads are important, however, in new suburbs.

The rule for our policymakers should be: build a road whenever the community will gain more from the new road than it will cost, and whenever the new road is a better option for the community than extracting more from the roads we’ve already got. But do not think of new roads as congestion-busting.

So what should be done?

Changing the way we use our existing infrastructure through pricing needs to be at the top of the agenda. This mean charging motorists for the congestion they cause.

Sydney and Melbourne need to consider introducing a congestion charge. That doesn’t mean more toll roads – it means charging people who drive at peak times on congested roads a small fee.

Because some people wouldn’t think it worth paying the charge at the busiest times of day, those who did pay would get a quicker and more reliable trip. People who can travel outside of the peaks would not have to pay, because there would be no congestion charge when the roads are not congested.

The increased cost to drivers could be offset by cuts to car registration fees. And any extra money raised by the congestion charge could be spent improving train, tram, bus and ferry services.

International examples show that introducing a congestion charge need not amount to political suicide. An initially sceptical public came quickly to accept, value, the reform when it was introduced in London and Stockholm.

The congestion equation for Sydney and Melbourne is only going to get more ugly as both cities continue to grow. We need more sophisticated policymaking to ease drivers’ road rage and frustrations.

![]()

Published at

Published at