I’m delighted to be here on the traditional lands of the Wangal and Gadigal peoples, and I’d like to thank David Borger and the Housing Now! team for the opportunity to speak at today’s Summit.

A lot has changed since I spoke at the inaugural Summit in late 2023. At that time, the newly elected Minns government was making the right noises on housing affordability. But the government had yet to meaningfully act.1This speech benefits from valuable research assistance from my Grattan Institute colleagues Joey Moloney and Matthew Bowes, and draws on an upcoming Grattan report on solutions to Australia’s housing crisis.

Today I’d like to take stock of what has changed in the past two years, and offer some suggestions about where the NSW government should go next, in order to make housing more affordable in NSW.

But first, it’s worth reiterating the extent of the challenge NSW faces.

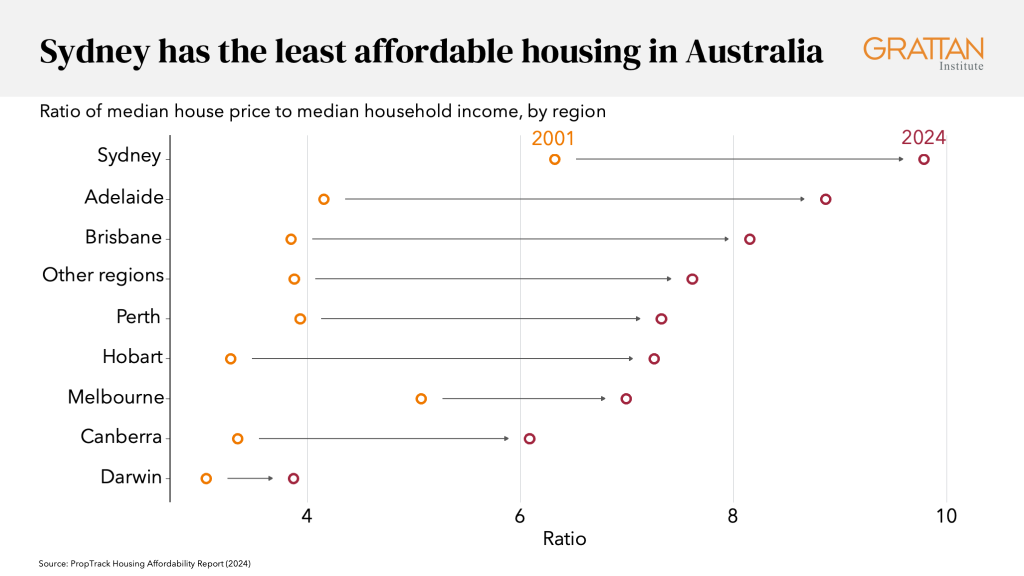

It’ll be no surprise to anyone in this room that Australia has a housing affordability problem. And Sydney remains ground zero for Australia’s housing crisis.

Median home prices have increased from about four times median incomes in the early 2000s, to more than eight times today (and around 10 times in Sydney). In regional NSW, too, house prices have risen faster than wages.

Low-income renters in NSW spend more of their income on housing – 35 per cent on average – than in renters in any other state.2Coates, B. (2024), There’s no time to lose in building the housing NSW needs: Submission to the NSW Inquiry into the development of the Transport Oriented Development Program, Grattan Institute.

And scarce and unaffordable housing is pushing many younger residents out of Sydney entirely.3Scully, P. and Jackson, R. (2024). Sydney is at risk of becoming a city with no grandchildren – Productivity Commission report finds. NSW Productivity Commission.

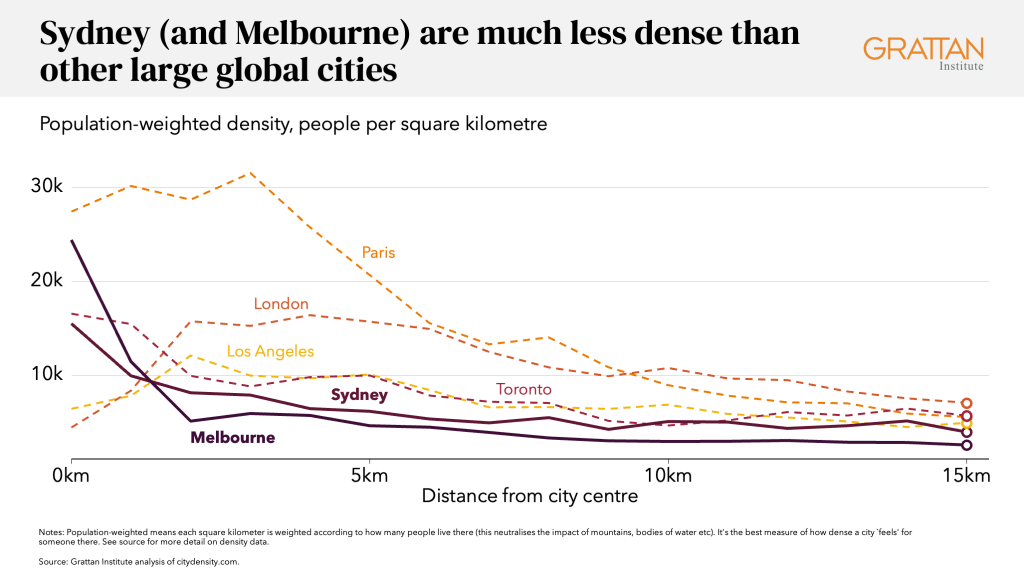

And it’s no coincidence that Sydney is one of the least dense cities of its size in the world.

If the inner 15km of Sydney offered the same number of homes as Toronto – a city that ranks similarly to Sydney on quality-of-life measures – it would mean an extra 250,000 well-located homes.4Grattan analysis of Nolan (2024) citydensity.com assuming average Sydney household size of 2.55, and NSW Productivity Commission (2023), Building more homes where people want to live, Figure 8.

That’s roughly two-thirds of the homes the NSW government needs to build to meet its target of 375,000 homes over five years as agreed by National Cabinet.

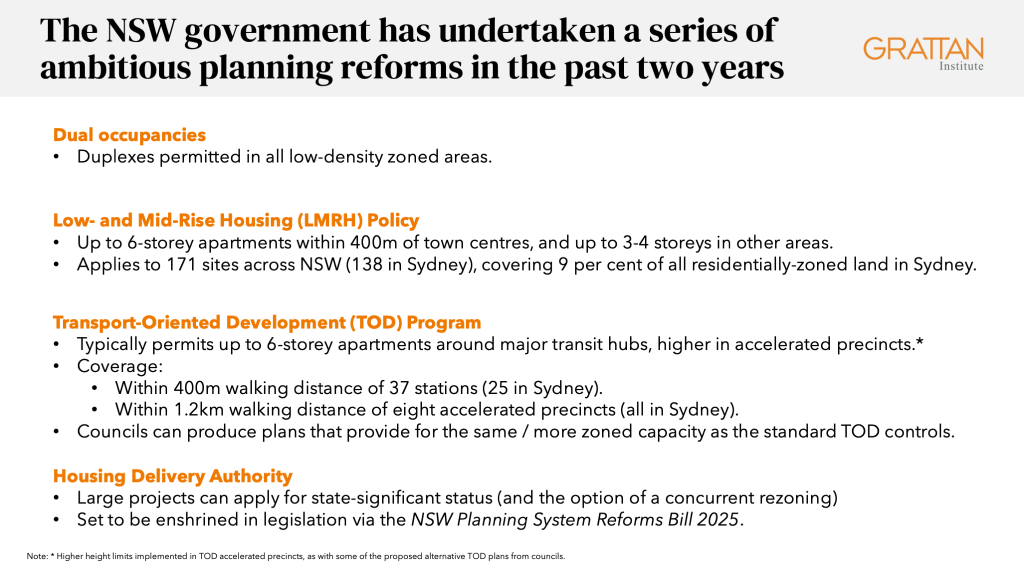

Over the past two years, the NSW government has made a series of policy announcements to get more housing built in Sydney.

The government’s new dual-occupancy policy permits two dwellings on all R2 – ‘low-density’ – zoned land statewide.

The Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Policy relaxes planning controls within 800m of 171 sites in NSW, allowing up to six-storey apartments in some areas, and three-to-four storeys in others.5There are different sets of standards – heights, floor-space ratios, lot size and width, car parking, etc – for different housing types (e.g. dual-occupancy, multi-dwelling housing of three or more dwellings on a lot other than apartments, and apartments), with some housing types only allowed in some zones. There are 138 sites in Sydney, covering 9 per cent of residential land.

The Transport-Oriented Development Program permits higher-density apartments around select transport hubs. Many councils are taking up the opportunity to present their own alternative plans to the standard TOD controls, with some, such as the Inner West Council, planning to unlock substantially more housing.6Our fairer future plan.

The government’s Housing Delivery Authority offers an accelerated approval pathway for major developments, including the prospect of concurrent rezonings.7The Housing Delivery Authority evaluates applications and makes recommendations to the Minister as to whether they should be declared state-significant developments based on criteria relating to project size and expected dwelling yield, likelihood of quick and uncomplicated commencement, and whether it contributes to the affordable housing stock. Link.

The are other reforms, including: density bonuses where developments include affordable housing; more ambitious housing targets for councils, and the new NSW Pattern Book offers a faster approvals for developments that use these designs.

And in the past two weeks, the NSW government has announced it will reform the Planning Act to make the planning system simpler to navigate.8Planning system reform to help build NSW’s future.

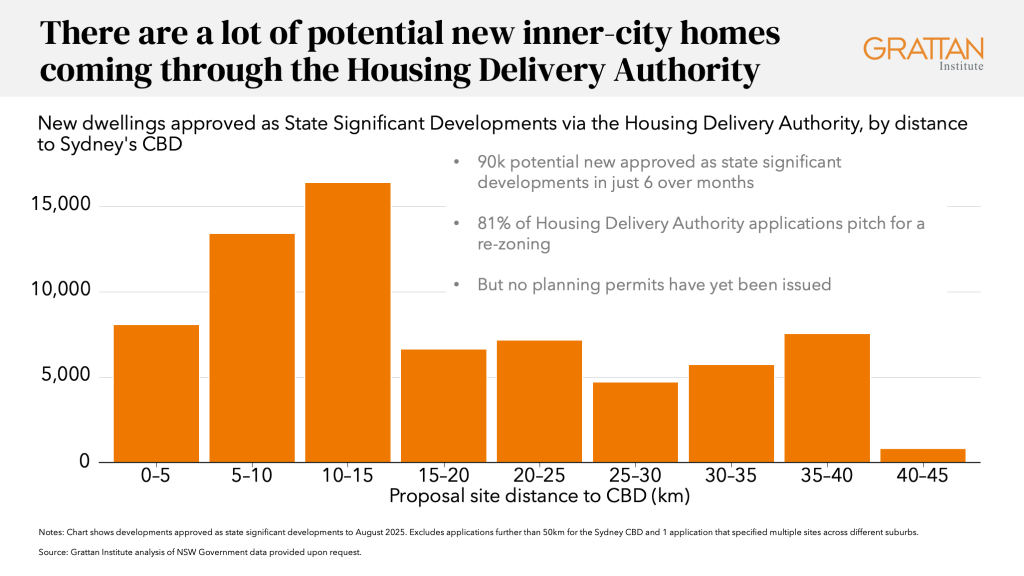

The Housing Delivery Authority, in particular, holds the potential to accelerate housing supply in NSW in the near term.

To late September 2025, after just seven months of operation, 261 projects have received status as state-significant developments. These projects account for 91,100 new dwellings.9As of 25 September 2025. NSW Government, More than 4,400 homes declared state significant, Ministerial media release. Further, 81 per cent of these applications have taken up the option to pitch for a concurrent rezoning.10Figures to August 2025 only. If a proposal exceeds applicable development standards by more than 20 per cent, it can be lodged along with a rezoning proposal. Of the new homes in the pipeline, 86 per cent stem from a rezoning application.

And the applications to develop new homes coming through the Housing Delivery Authority are concentrated in inner-city areas where demand is highest.

These numbers suggest the Authority may be effective at circumventing council opposition to building new homes in many well-located areas in Sydney. Although we must wait until we start to see developments approved via the pathway, and more housing built, before we can truly pass judgement on its effectiveness.

But the Authority is only necessary because it offers a circuit breaker to bypass the sclerotic NSW planning system. And it’s here – in the thicket of controls that govern what can be built where across Sydney – where the NSW government still has a lot of work to do to achieve its goals.

Historically, most planning reforms have focused on streamlining development approvals: making it easier for new housing to be built where it is already allowed.

But the biggest constraint on getting more housing built in Sydney isn’t slow or uncertain processes. It’s the fact that it’s illegal to build more housing on most valuable inner-city land.

NSW has a planning system that says “no” by default, and “yes” only by exception.

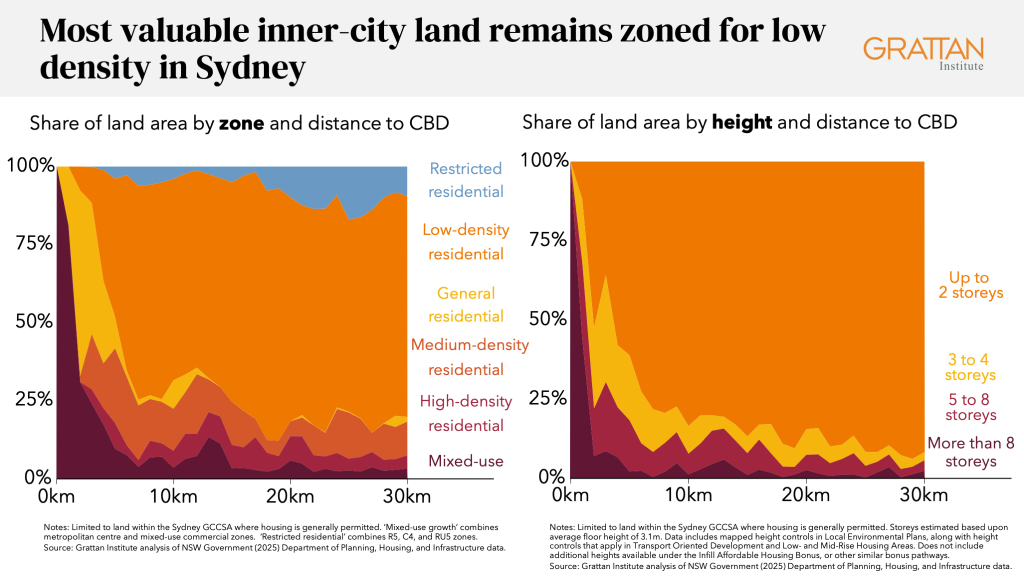

For example, just 5km from the Sydney CBD, more than 50 per cent of the residential land is zoned for low-density housing via the restrictive ‘R2: Low-Density Residential’ zone, which typically permits only one or two homes per block, and rarely more than two storeys.

In fact, 50 per cent of residential land in Sydney is zoned for such low-density housing.11Measured as the Greater Capital City Statistical Area (GCCSA), less land zoned for greenfields expansion. In addition, much of the land within 2-to-4km from the CBD is zoned ‘R1: General Residential’, which in many instances is similarly restrictive. Grattan analysis of Department of Planning, Housing, and Infrastructure Spatial Data.

Further, more housing in many areas of Sydney is constrained by a thicket of other controls, mostly set locally by councils, which further limit what housing can be built.

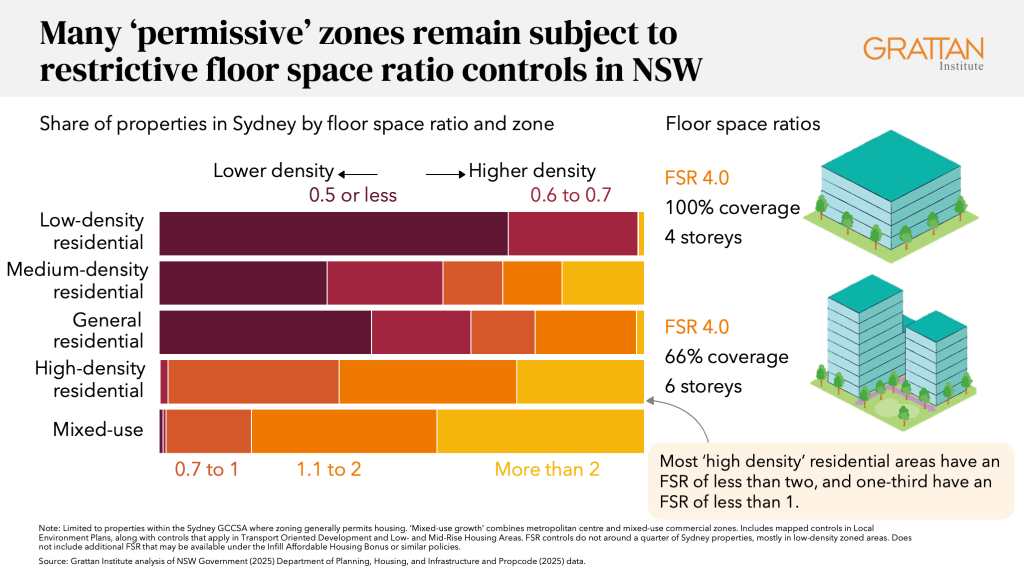

Much of the land zoned for higher-density housing in Sydney is subject to highly restrictive maximum floor-space ratios.

For example, a maximum floor-space ratio of four means that a development can go to four storeys across the entire site, or to six storeys if it covers only two thirds of the site.

But well over half of land zoned for high-density residential within 30km of Sydney’s CBD is subject to a maximum floor-space ratio of less than two, and one third is limited to a floor-space ratio of less than one.12Grattan analysis of Department of Planning, Housing, and Infrastructure Spatial Data.

A maximum floor-space ratio of one allows only a two-storey building on half the site, or a one-storey building right up to the boundary. Notably, floor-space ratios are rarely used in Victoria’s planning system and were recently removed in the ACT.

Similarly, outside of Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Areas, only around a third of Sydney councils allow flats in R3, the ‘medium-density’ zone.13Grattan analysis of various NSW council Local Environment Plans.

As a result, many zones in NSW don’t do what they say on the tin.

The key problem is that the NSW government cedes more power to local councils to set the controls that govern what can be built where, compared to states like Victoria.14In NSW, the state-level template that councils use to devise local plans – the ‘Standard Instrument’ – defines zones without specifying what built-form controls, such as building heights, the state government expects the zone will allow. Rather, council plans specify the controls that apply – such as housing types, heights, site coverage, floor-space ratios, and setbacks – separately. See: NSW Government (2006). Standard Instrument—Principal Local Environmental Plan (2006 EPI 155a).

Crucially, a lot of the NSW government’s recent reforms pay undue deference to many of these restrictive local zones, which limits the extra housing that these reforms can support.

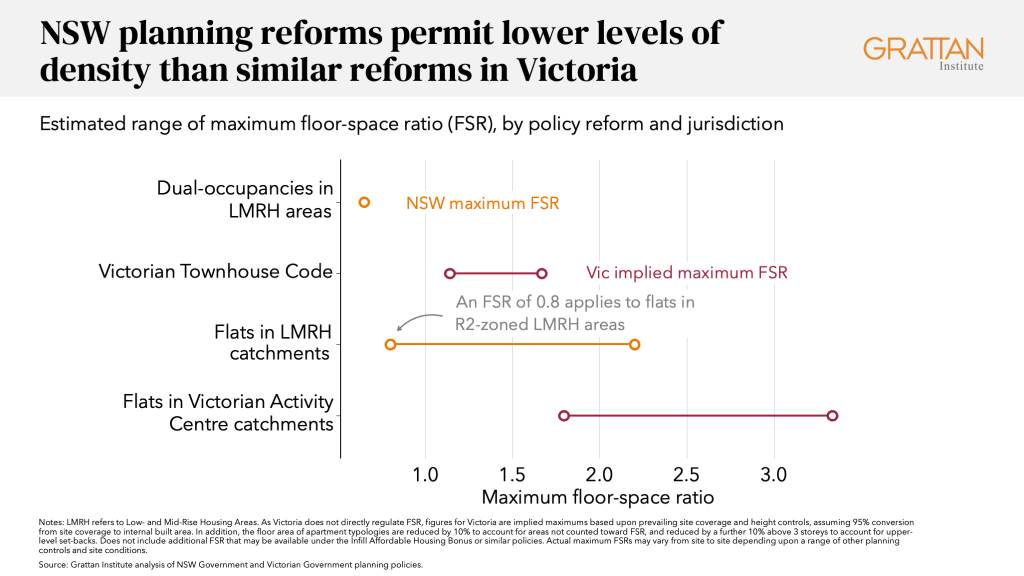

For example, the government’s dual-occupancy policy permits a maximum floor-space ratio of 0.65. Whereas the same site in Victoria could permit up to three times as much floorspace under the Victorian government’s new Townhouse Code.

In the 62 per cent of Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Areas in NSW where councils have applied the low-density R2 zone, new apartments are limited to just two storeys.

And even in Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Areas that now otherwise allow four or six storeys, restrictive maximum floor-space ratios of 1.5-to-2.2 apply.

As a result, the NSW government’s policies permit much less new extra housing on a given site than Victoria’s Activity Centre catchments now allow.

These choices have an enormous impact on how much extra housing is allowed under the NSW government’s reforms.

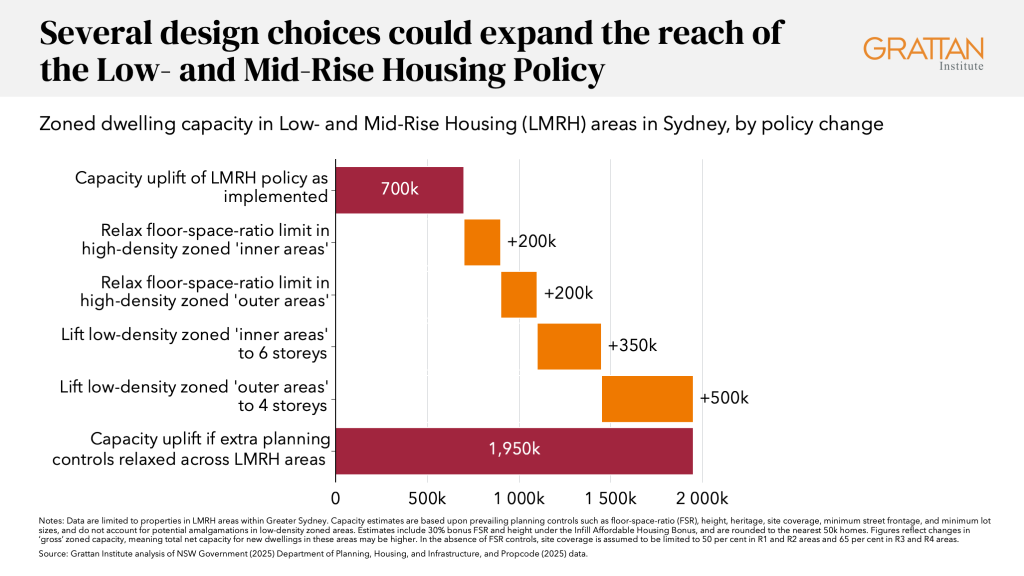

For instance, we estimate that the Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Policy has boost zoned capacity for more housing across Sydney by 700,000 homes.

But were the NSW government to give full effect to the policy’s intent, it could support nearly three times as much extra housing.

For example, if restrictive floor-space ratio requirements were removed across higher-density zoned areas covered by the policy, and built-form was instead regulated through reasonable setbacks and site-coverage ratios, the zoned capacity uplift from the reform would increase by up to 400,000 dwellings.

Allowing six storeys in ‘inner areas’ covered by the Policy that are currently zoned for low-density residential – those within 400m – could add capacity for another 350,000 homes.

And permitting 4-storey developments in ‘outer areas’ of the Policy that are currently zoned for low-density residential would boost capacity by a further 500,000 homes.

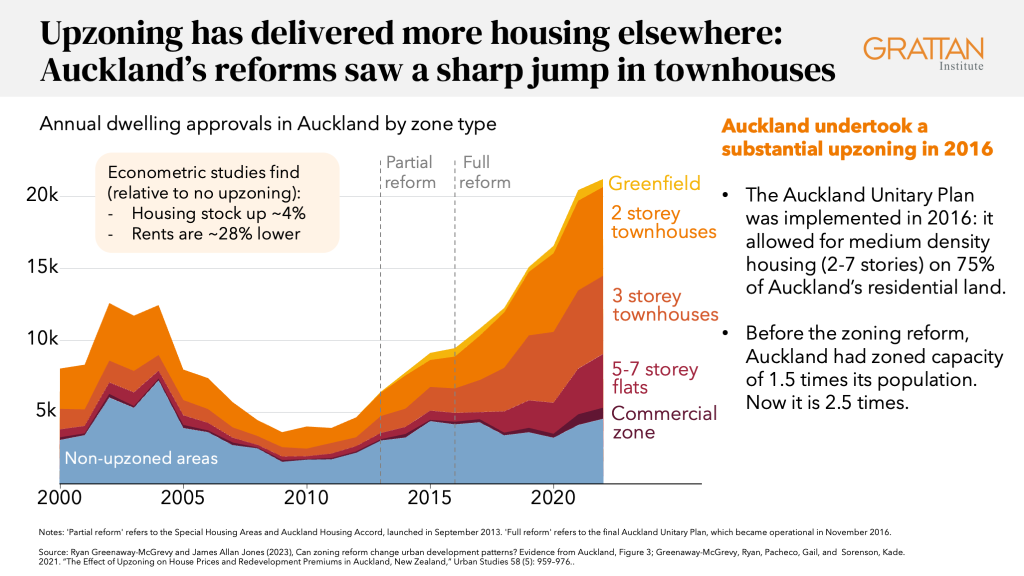

After all, the lesson from planning reforms in Auckland and elsewhere is that relaxing planning controls can deliver a lot of new housing, but you need to create a lot of extra zoned capacity to get more housing built.

For instance, when Auckland rezoned about three quarters of its suburban area in 2016, subsequent studies show that the policy boosted the housing stock by up to 4 per cent within six years, and reduced rents by 28 per cent, compared to where they otherwise would have been.15Greenaway-McGrevy, R. (2024). ‘Causes and consequences of zoning reform in Auckland’. Cityscape 26.2, pp. 413-434.

Most of this new stock was extra townhouses and small apartment buildings, rather than taller apartment buildings – precisely the kind of housing the Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Policy aims to deliver, and which is most cost effective to build in the current climate.

Before the reforms, central Auckland had zoned capacity of about 1.5 times the existing population. Yet housing was still scarce and expensive, because much of that capacity was in low-demand areas where it wasn’t profitable to build, or where existing homeowners were unwilling to move.

Auckland’s reforms increased zoned capacity for extra housing by 60 per cent, and that delivered a lot of extra housing.

In fact, the experience of Auckland and elsewhere suggests we should expect no more than about 1 per cent of the extra zoned capacity to be built out each year.

There’s no doubt that reforms to allow more housing in Sydney are difficult, which is why they’ve been left in the too-hard basket until recently.

For too long, many local councils in Sydney, especially those closest to the city, have been unwilling to allow enough housing to be built across the inner- and middle-rings of Sydney.

The NSW government deserves a lot of credit for taking steps to get more housing built. These reforms will have a real impact on getting more people into homes, and faster.

But the government still has a long way to go to deliver on its goal of making housing substantially more affordable in NSW.

That means tackling the thicket of rules – restrictive low-density zones, maximum floor-space ratios, and prohibitions on dwelling types – that still say “no”, rather than “yes”, to more housing across so much of Sydney.

In short, keep pushing, because the job is not yet done.