I am delighted to be here with you all tonight on Wurundjeri land, and I would like to extend my respect and admiration to the Wurundjeri elders and recognise their continuing connection to this country.

[1] Thank you to the Faculty of the Business and Economics for the invitation to speak on this momentous occasion. This is a first for me: I have given several lectures established to honour people whom I greatly admire. But this is the first time the person in question is still alive – and, indeed, right here in the room!

Tonight’s lecture not only honours the huge contribution of Professor John Freebairn AO, it also marks his retirement from full-time academic life. And although I am told John has been threatening to retire for years, he assures me that this time he really means it. John, I very much hope I can do some justice to your extraordinary legacy this evening.

John has made a huge contribution to Australian economics and policy through his decades‑long career as Professor of Economics and the Ritchie Chair of Economics here at the University of Melbourne, as well as through stints at Monash University, the Melbourne Institute and the Business Council.

I have always regarded John as the ‘policymakers’ academic’ – he is one of the few special people who has combined a thriving academic career with a deep, hands‑on engagement with Australian policy.

Politicians and public servants over the decades have drawn on John’s wisdom. Many have described to me John’s rare magic at combining academic rigour with clear communication and a talent for finding a cut‑through line.

John’s major academic and policy contributions have been in the area of tax reform.

Indeed, John’s academic contributions read like a tax reform to‑do list:

- In 2002, he published ‘Opportunities to reform state taxes’,[2] which made cogent arguments for replacing stamp duties with broad-based land and payroll taxes.

- In 2005, he argued for closing loopholes and exemptions in the income tax base.[3]

- In 2012, in the wake of the Henry tax review he explored and expanded on options for more neutral taxation of savings income.[4]

- Other publications have explored options for resource rent taxation[5] and ways in which a higher or broader GST could be used to reduce more distorting stamp duties and income taxes.[6]

Pick up the AFR on any given day and you will find op-eds making variants of these arguments, grounded in the important work John has done unpicking the efficiency and equity impacts of different options for reforming the tax base.

John has also made the case for these reforms directly to government, through his work as a consultant to the Henry tax review and on the review Panel for the NSW Federal Financial Relations Review, among other reviews.

And while John has done the hard work of tilling the ground, and has no doubt been pleased with some of the progress made on tax reform, much of the broad agenda he has articulated remains on the shelf.

So the question I want to ask tonight is: Why?

Why, after so many decades of discussion, so many points of broad economic consensus, does tax reform remain so challenging?

Is progress possible or is tax reform simply an impossible dream?

Part 1: Why reform taxes?

To answer this question, we need to first understand why someone with John’s rare talents decided to use them making the case for tax reform.

The bottom line is, tax matters. It matters to all of us: how much we collect and how we collect it has implications for economic activity, governments’ capacity to deliver services, and inequality.

The challenge we face when we talk about tax reform is that different people start with very different objectives.

So let’s unpack some of those.

The first is economic efficiency. Economists rightly focus on the fact that how we collect tax – that is, what we tax and how much – affects the ‘economic drag’ created by the tax system. Almost all taxes come with some loss of welfare, but some drag on growth more than others.

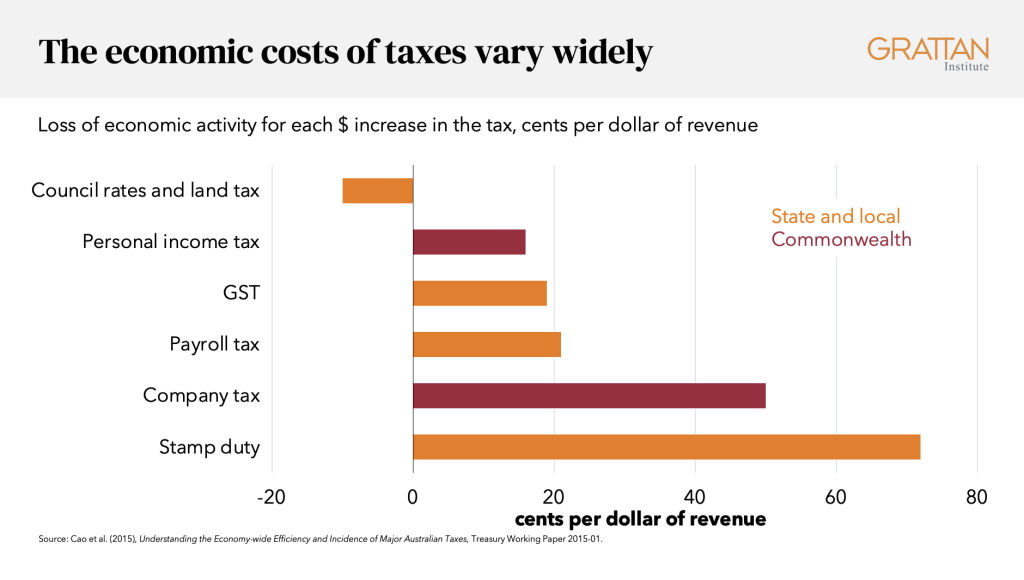

In a static sense, this can be measured by the marginal excess burden – how much economic activity is lost for every dollar collected. As Treasury and others have reminded us, this varies significantly between taxes.

And while there can be big differences in the estimates different modellers come up with – a point I will return to – there is broad agreement that a ‘tax mix switch’ to move from higher burden to lower burden taxes would deliver an economic dividend.

The most clear‑cut example is moving from stamp duties to taxes on land.

As you can see from the chart, stamp duties are among the most inefficient taxes available. Treasury estimates suggest that every dollar collected may reduce economic activity by up to 72 cents.[7]

Stamp duties discourage people from moving to housing that better suits their needs, and sometimes they discourage people from moving to better jobs. Overall, they distort choices and gum up the economy.

In contrast, property taxes – which are levied on the value of property holdings – are highly efficient. If they are designed well and applied broadly, they do little to change people’s incentives to work, save, and invest. Property taxes are also a more stable revenue source than stamp duties and so make state budget management a much easier task.[8]

None of this is to say that a decision to replace stamp duties with land taxes would be easy either practically or politically: the transition issues are thorny and the politics is notoriously challenging. Nonetheless, I want to highlight it the land tax/stamp duty swap an example of a case where there is a broad consensus on efficiency benefits. Indeed, it may be the only policy where you could find the full spectrum of academic experts and think tanks in furious agreement.

Another reason we might advocate for tax reform is budget sustainability and the need to future‑proof our tax system.

At a time when the Treasurer has just delivered the first budget surplus in 15 years,[9] and we are seeing apparently endless revenue ‘upgrades’,[10] it may seem strange to be having this conversation.

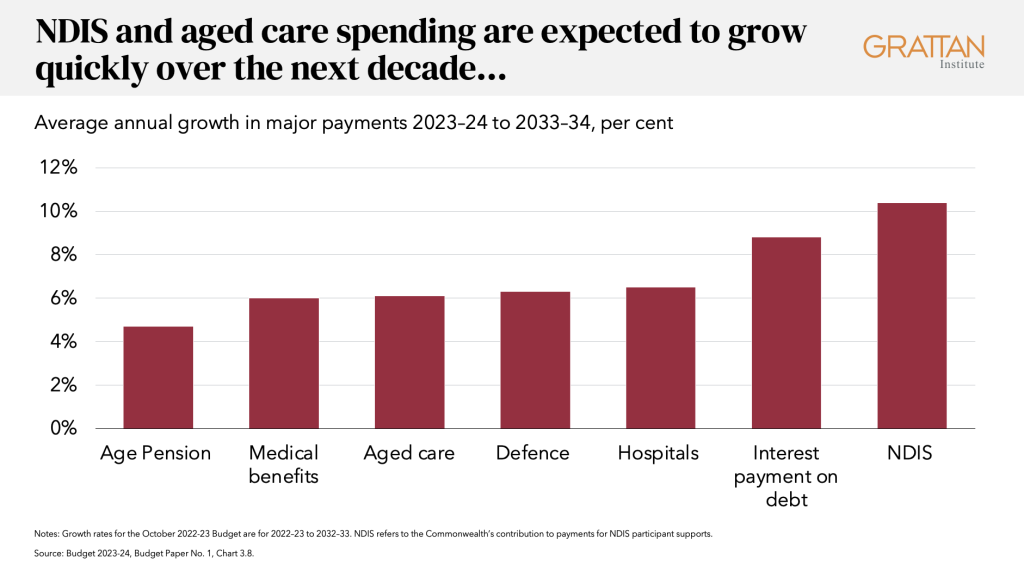

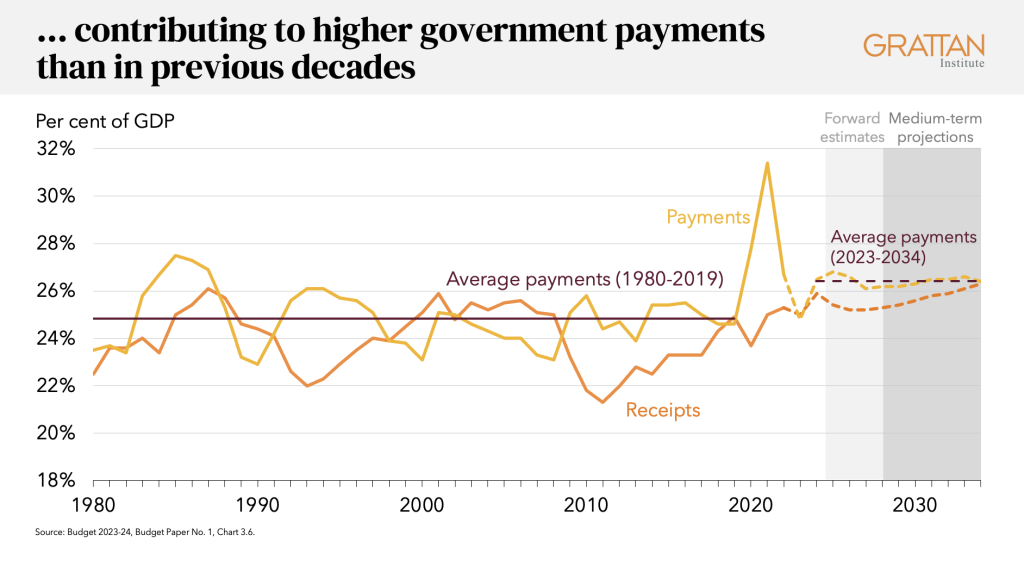

But the fiscal challenge is a slow burn. Spending on the NDIS, defence, the Medicare Benefits Schedule, and aged care are all expected to grow strongly over the next decade.

Government spending overall is projected to average 26.4 per cent of GDP over this period, compared to less than 25 per cent over the three decades before COVID.

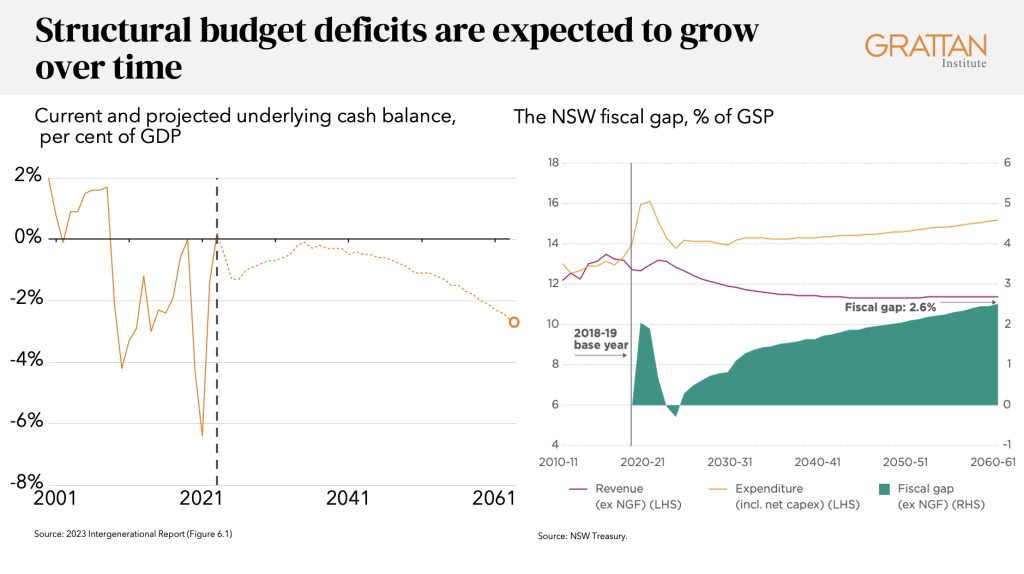

Revenues have not kept up. Structural budget deficits this decade are projected to average 0.6 per cent of GDP, or about $12 billion a year in today’s dollars. These estimates systematically understate the scale of the challenge because of their persistently optimistic assumptions around containing spending growth.[11]

The latest Intergenerational Report from the Commonwealth government reminds us that the ageing population and the fallout from climate change will only see this fiscal challenge grow over the next 40 years.

The same is true of state budgets. Currently NSW is the only state to release its own Intergenerational Report. It, too, suggests that the ‘fiscal gap’ – the gap between revenue and expenditure – will widen over the coming decades.

The implications of not taking policy action are clear: we are asking future generations to bear the costs of today’s inaction.

Ultimately, there are three levers that governments can pull to address long-term budget challenges: they can make economic reforms to ‘grow the pie’, they can increase taxes, and they can reduce spending.

Pursuing policies to boost growth is critical. Much of Grattan Institute’s work has focused on policy change to ‘grow the pie’. And I look forward to pursuing this in a big way when I join the Productivity Commission in a couple of weeks’ time.

But, as Grattan highlighted in our Back in black? report released earlier this year, we cannot rely on higher growth alone to close the budget gap.

Given the scale of the challenge, governments will also need to find ways to reduce spending and/or boost revenue. After a decade of looking at this challenge I have come to the view that we will need to do both. The scale of the challenge, and the greater buy‑in that can be achieved when the costs are spread across the population, are arguments for looking to both sides of the budget for answers.

But this personal view reflects a value judgment: that deep cuts to services would be harmful to equity and our longer-term capacity to thrive as a nation.

Of course, others might have different value judgements, and argue that taxes should not grow as a share of the economy. But – given the structural forces of an ageing population, fallout from a changing climate, stronger spending on defence in response to shifting geo-politics, and the long-term trend for health expenditure to rise as more and better technologies become available – such a position can only be regarded as credible and intellectually honest if it comes with a complementary list of very sizeable cuts to major spending programs.

Certainly, the usual election ‘go‑tos’, such as ‘cutting the public service’, or ‘cracking down on welfare cheats’, are largely illusory: they will not yield savings that are even in the ballpark of what is required – as I’ll come back to.

Now, if we do accept that some additional revenue is needed to respond to the structural challenge outlined, then we want to make sure that additional revenues are collected with the lowest possible economic costs. In fact, this can also help us grow the pie: more efficient, less distorting taxes are one of the PC’s ‘enduring policy priorit[ies]’ for productivity growth.[12]

On the other hand, if we do nothing, we may end up on the path of least resistance: collecting ever more revenue through ever‑creeping taxes on wage and salary earners. Bracket creep may be the most politically painless way to raise revenues but it is far from the best.

Tax reform for budget sustainability should aim to broaden the base of income taxes – looking at loopholes and overly generous concessions, as well orientating our collections toward more efficient bases such as consumption, wealth, externalities or resource rents. In other words, we need to revisit the John Freebairn back catalogue!

There are also other worthy reasons why particular reforms may be worthwhile.

Simplicity is one. While often given lip service, anyone looking at the Australian tax system can only conclude that simplicity has not been weighted heavily in tax policy decision making over the years.[13] The legislation just for income and fringe benefits tax assessment runs to 8,108 pages across three acts.[14] It’s no wonder that almost two-thirds of Australian taxpayers use tax agents,[15] a much higher rate than in many comparable countries.[16]

Policies that simplify the tax system for individuals – such as a standard deduction, which would reduce the need for tax returns for the majority of Australians – would also represent important reforms.[17]

Another reason is ‘fairness’ or equity. While the amount of redistribution to be achieved through the tax system is ultimately a values question, there are a range of ways in which our system is unambiguously falling short.

One is the very different tax treatment for people in similar economic circumstances.

High stamp duties mean that a household that moves a lot pays a lot more tax than an otherwise identical household that stays put.

A person who puts their life savings in a bank account is taxed much more heavily on the resulting income than the person who makes additional contributions to their super or buys a more expensive home to live in.

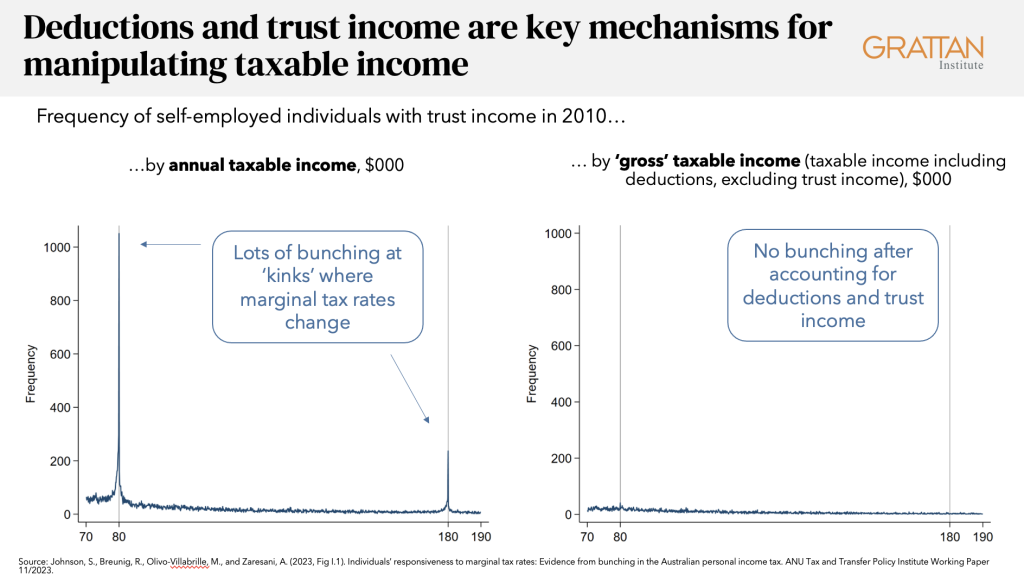

Second is the myriad ways that well-advised high‑income earners can reduce their effective tax rates. Australia’s complex system of carve-outs offers considerable leeway for individuals to massage their taxable income to avoid high marginal tax rates.[18] An illustration of this is the distinctive bunching patterns that we see around ‘round numbers’ of tax refunds – suggesting taxpayers and their agents are able to manipulate taxable income to some degree. Deductions and trust income are key mechanisms for this manipulation, for those with access to these instruments.[19]

And a third reason why a particular reform might be worthwhile is intergenerational equality. As I and others have long argued, the degree of age segregation in the current tax system, where a retiree household on $100,000 pays half the income tax of a younger household on the same income, is neither defensible nor sustainable.[20]

To be clear, all these rationales for tax reform – efficiency, sustainability, simplicity and fairness – are valid. But many a tax reform roundtable has gone awry because people are talking past each other in terms of what they are trying to achieve.

In reality, there are few reforms that will achieve all these objectives at once. But if we want to build a constituency for any reform or reform package, it is critical that we are crystal clear about what we are doing and why. As a member of one of Australia’s earliest tax reform committees declaimed in 1979:

It is as if we were entangled in a boggy tropical jungle from which we can descry a whole set of habitable hilltops to which we might struggle over the years ahead, but that they are all in different directions… To get moving at all we need therefore first to achieve some wide political consensus upon the ultimate destination.[21]

Part 2: Why is tax reform so hard?

Given the many compelling rationales for tax reform I’ve touched on here, why is it that we have made so little progress over the years?

There are many reasons tax reform has proven a hard mountain for governments to climb.

Some are external – well-resourced vested interests running interference, lack of expert consensus, and the challenging media environment, for example. Some relate to politics itself, and to the seeming irresistibility of a good tax scare campaign.

And some obstacles to reform are deeply human. Some taxes just ‘hurt’ more than others for a given dollar collected, which means that some of the changes most attractive to economists are not attractive at all to real people.

Let’s address them in turn.

Who’s in the room: muddying the waters on tax changes

As Niccoló Machiavelli wrote:

there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things, because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new.[22]

A key reason that we have failed to shift the dial on tax is the losers are often concentrated and vocal, and the winners are diffuse and often disengaged.

This challenge this creates is supercharged when combined with the aggressive tactics of some of the impacted groups and the relatively weak checks and balances on vested interest influence in Australian politics.

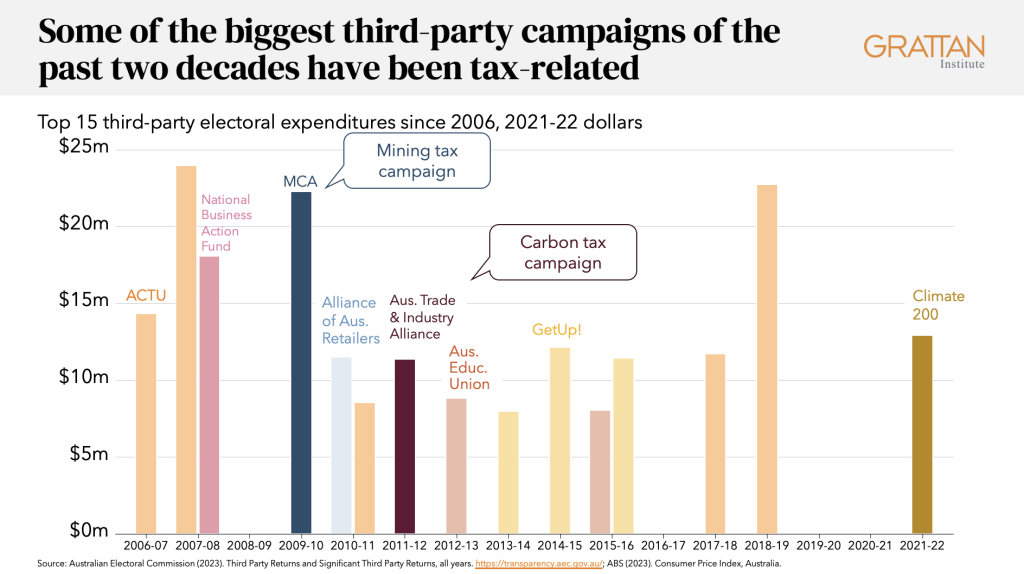

The most evident manifestation of vested interest pushback on tax is the public campaign.

Some of the biggest public advertising campaigns mounted over the past 15 years by groups other than political parties have been tax-related.

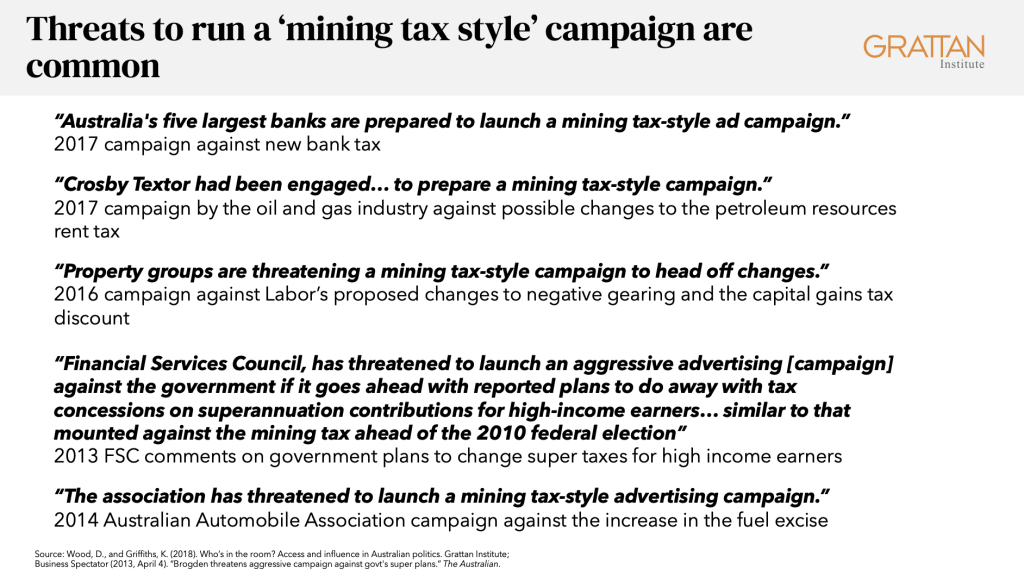

The perceived success of the mining industry campaign against the Resource Super Profits Tax means threats of a ‘mining tax-style campaign’ have become standard operating procedure for well-resourced groups fighting policy battles.

Just the threat of a big spending campaign can bring governments to the negotiating table. The mining industry spent only an estimated $22 million of its reported $100 million advertising budget[23] before Julia Gillard called for an advertising ceasefire and embarked on ‘good faith’ negotiations with the industry.[24]

Amassing a big war chest is one way to be effective. Others have generated a very effective bang for buck through fear and misinformation.

One of the most egregious examples of this was during the 2019 election campaign when certain real estate agents wrote to tenants claiming that ‘rents will rise’, not to mention the ‘whole economy would be in jeopardy’, if Labor were to win the election and enact its proposal to wind back negative gearing and reduce the capital gains tax discount.[25] The Real Estate Institute of Australia claimed that this message reached eight million Australians through its direct mail and Facebook campaigns.[26]

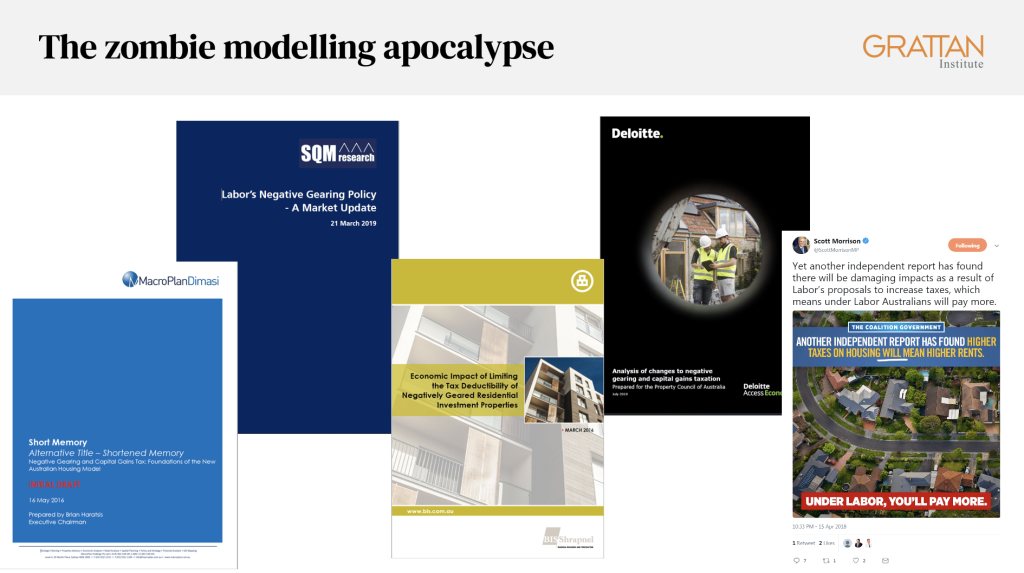

Another high‑return technique is commissioning dodgy economic modelling to muddy the public debate.

Now I have no problem with economic modelling – indeed, some of my best friends are economic modellers. Modelling can be a useful tool for giving a sense of the broad direction and orders of magnitude of the economic effects of policy change. But it’s only as good as its assumptions: ‘garbage in – garbage out’ as the expression goes.

And my concern is that ‘garbage out’ modelling receives as much, if not more, space in the public sphere than high‑quality modelling, probably because its eyebrow‑raising claims make for more alarming headlines.

If I can return to negative gearing by way of example.

In 2016, a consulting firm put out a report purporting to show the effects of removing negative gearing on the Australian economy. The results were spectacular: changing negative gearing – a policy that was estimated to raise $2.1 billion a year in extra revenue in their model – would wipe a full $19 billion off GDP. Or, to put it another way, every additional dollar of tax collected would wipe more than $9 off Australia’s economic activity.[27]

Now, if you recall the chart I put up earlier on the economic hit from certain taxes, you will remember that the estimated economic harm from stamp duty – almost universally accepted by economists as the most damaging tax – was estimated at 72 cents in the dollar.

Estimates of economic drag more than ten times this large for any tax change simply don’t pass the giggle test. The report should have been dead on arrival. But the laugh was ultimately on us. Not only did the modelling run uncontested on the front page on Australia’s national newspaper, it received multi-page spreads in the major tabloids and was tweeted and referenced in Parliament by Australia’s then Treasurer.[28]

That’s a lot of bang for buck for a report that probably cost less than $100,000 and was commissioned by an anonymous source.[29]

Even after the report was comprehensively discredited, its claims would sometimes emerge zombie‑like in public debates years later. Not to mention the host of other reports of variable quality commissioned by those with a similar interest in stoking community alarm.

Another common tactic for those seeking to stymie reform is to seek to influence decision makers through lobbying and political donations.

Lobbying itself is not a problem. Policy is a contact sport and we should expect businesses, individuals, and others to advocate for their own interests in policy debates. Hearing from a wide variety of interests supports better policy development and helps avoid unintended outcomes.

But the challenge is that existing systems around political access and consultation mean that well-resourced interests often have much greater access and influence than other groups.

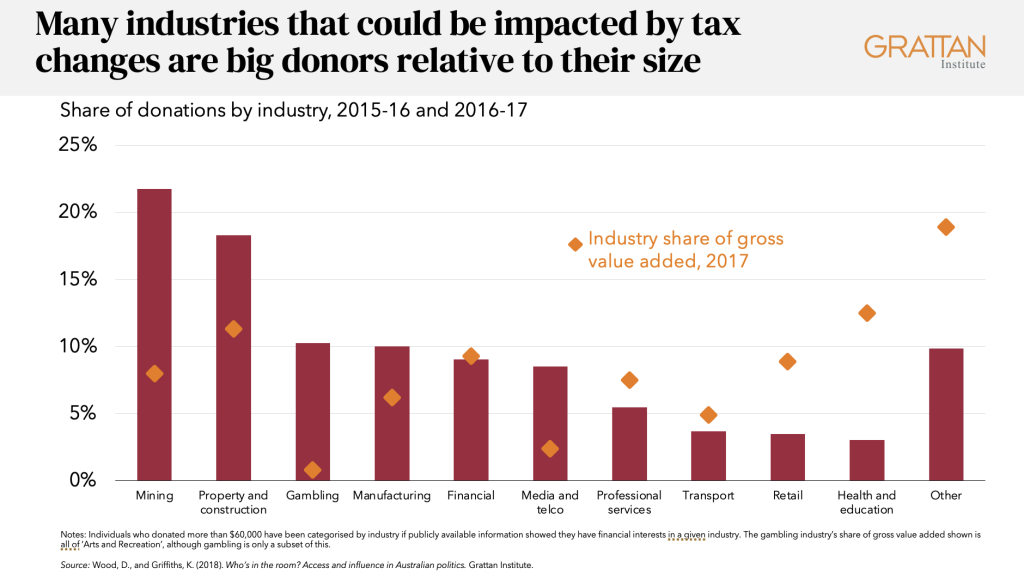

Grattan’s 2018 report, Who’s in the Room? found that industries with the most to gain or lose from government decisions received many more meetings with federal government ministers than other groups.[30] These industries – including mining, property development and gambling – were also much more generous donors relative to their contribution to the economy than other sectors.

And money can buy access, too: whether it literally buys a seat at the table with a political leader at a fundraising dinner, or opens doors thanks to the sense of reciprocity that a large donation can create. Our work showed that in Queensland and NSW – where ministerial diaries are published – major donors had a pretty good strike rate at getting precious meetings with senior ministers.[31]

Interest groups also sometimes use donations in ways that make it appear they have an explicit expectation of a particular policy outcome in return for their money.

The salary packaging industry, to take one example, is a classic case of an industry that thrives or flounders by the stroke of a government pen.

In 2013, the Labor Government announced plans to end the favoured tax treatment of company cars, leading to ‘sleepless nights’ for industry players.[32]

Lucky for them, then, that the Coalition announced it would reintroduce the tax breaks if it won the 2013 election.[33] A month later, the salary packaging industry association donated $250,000 to the Liberal Party, and almost nothing to Labor.[34]

Flash forward to the leadup to the 2016 election. Labor complied with the industry’s request for a letter explicitly stating it would not roll back these tax breaks if re‑elected. Both parties declared $165,000 in donations and other receipts from the industry associations[35] – including a $120,000 donation to the ALP made just eight days after Bill Shorten provided the policy guarantee.[36]

Despite being some of the least justifiable in our tax system, these tax breaks are still with us today. And indeed, they have even been supercharged in the name of speeding up the transition to electric vehicles – a policy the Productivity Commission has shown costs many times more than other policy options for every tonne of abatement.[37]

Of course, the challenges of disproportionate vested interest influence aren’t confined to tax policy, but they can certainly illustrate some of the other challenges I want to come to.

Models at 50 paces: the challenge with lack of expert consensus

Debates are more vulnerable to being co-opted by vested interests where there is little counterbalance from other forces. This is particularly true where there is a lack of consensus among experts.

In a 2021 report examining why major policy change in Australia had become so difficult, Grattan’s former CEO John Daley concluded that vested interests were much better able to stymie reform if the evidence base was weak.[38]

It is simply much harder for politicians to make the case for change if there is strong disagreement among experts about whether change is a good idea.

This was evident in the 2016 policy debate about whether to reduce company tax rates. The Turnbull government proposed cutting the company tax rate from 30 per cent to 25 per cent in a bid to stimulate business investment and boost economic activity.[39]

But the main groups modelling the change did not even agree about the direction of the impact on national income, let alone the magnitude.[40] Indeed, sometimes scratching the surface of the tax literature can leave one feeling slightly discombobulated.

A synthesis of 45 studies on the impact of a host country’s tax rate on foreign direct investments suggests a median estimated impact of a 1 percentage point cut in the corporate tax rate is a 2.3 per cent increase in FDI. However, the range is eyewatering, including a small number that suggest very large impacts and a not‑insignificant number that suggest no change or a decline.[41]

Given the importance of expert input into tax debate, more empirical research into some of these questions would be highly valuable. To date we have relied a lot on theory to understand the impacts of different taxes.

We would also benefit from some type of synthesis of expert modelling in major tax debates, to at least provide clarity on points of agreement and major sources of difference in models. Experts at 50 paces serves no one well – least of all people who believe the status quo needs to change.

I smell a beat up: the role of media sensationalism

The longer I have worked in tax policy the more I have been confounded by the role of media in tax reform discussions.

On the one hand, some segments of the media regularly hand‑wring about the importance of tax reform for economic prosperity. On the pages of the AFR, for example, tax and IR reform are shorthand for a ‘serious’ economic agenda.

On the other hand, across the media, the excitement of a tax beat‑up appears an almost irresistible temptation.

Indeed, the media feeds, and feeds on, the scare campaign reflex of the political class – whereby even a mention of tax changes by a political opponent is almost instantly weaponised.

Media outlets give a disproportionate share of airtime to tax changes compared to other government decisions.

Let’s take this budget’s super tax changes as an example.

This modest change to wind back tax breaks for only 80,000 of the most well-off with more than $3 million in super was labelled a ‘class war’,[42] a ‘death tax by stealth’[43], and a ‘super-sized broken promise’.[44]

It received front-page coverage from major tabloids, wall-to-wall coverage in our two national papers, and generated more than 1,200 media articles in the month after it was introduced.[45]

In contrast, the government’s policy to expand government paid parental leave to 26 weeks and encourage more dads to take leave – benefiting around 180,000 families a year[46] – received less than a quarter of the coverage in the four weeks after it was announced.[47]

This was essentially a re-run of the super‑sized backlash faced by the Coalition in 2016, which also followed proposals to wind back the most generous super tax concessions for high‑balance accounts.[48]

Commentators quickly decried the ‘super debacle’[49], claimed that the debate was infested with ‘the politics of envy’,[50] and warned Scott Morrison that ‘this could be the rock on which you perish’[51]. The relevant Minister even had her pre-selection threatened.[52] Again, by way of contrast, a big new youth jobs initiative in the same budget, worth $750m over four years, received about a quarter of the attention over the same period.[53]

There are many more examples I could share.

The big reason tax stories are irresistible is they are easy to write.

Tax changes neatly lend themselves to a ‘winners and losers’ framing.

And it is losers that make for good headlines. The media is particularly adept at focusing on ‘sympathetic’ losers, regardless of the how few of them there are, or how small the negatives might be in terms of the overall impact of the policy.

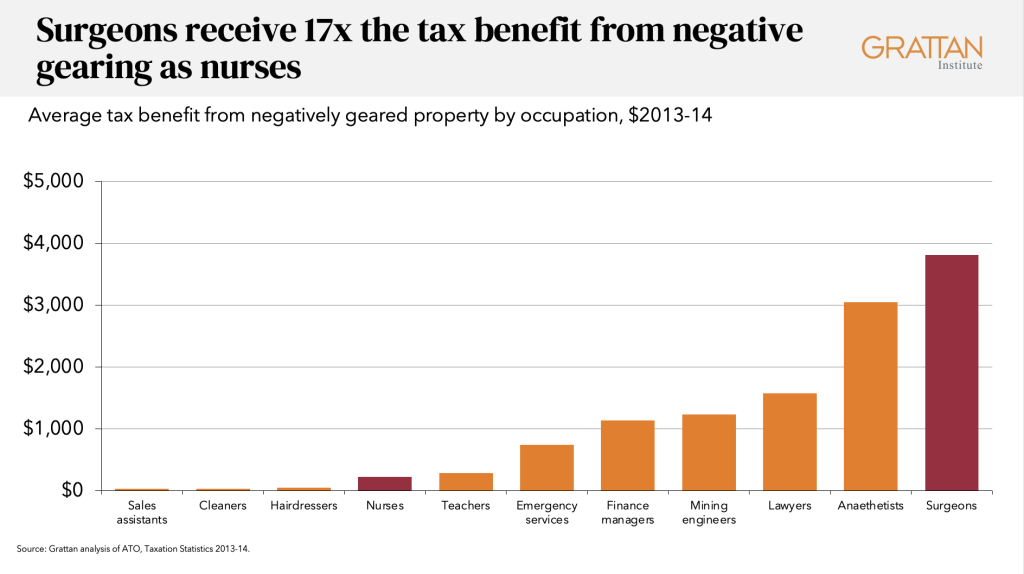

So, for example, in the negative gearing debate, it was teachers and nurses who were trotted out as the ‘real’ losers of potential tax changes.

I have to give a particular shout out here to the AFR, which managed to track down a married couple – both nurses – with two children, and no fewer than four negatively geared properties.[54] I really hope that reporter got a raise!

As we showed in 2016,[55] there are of course nurses and teachers using losses on their investment properties to reduce their taxable incomes (at that time around 12 per cent of teachers and 9 per cent of nurses respectively). But they were much less likely to use investment tax breaks than anaesthetists (29 per cent), surgeons (27 per cent) and finance managers (23 per cent).

And the average surgeon reduce their tax bill 17 times as much as the average nurse.

The challenge with this relentless focus on visible losers is that the underlying rationale for the change gets drowned out. The ‘losers’ from the status quo are invisible: we don’t hear the stories of the businesses not started, nor the empty-nesters who would have happily downsized but for the whopping stamp duty bill.

This is particularly true because the biggest winners from tax reform are much harder to put on the front page of the newspaper – except as a cute photo-op for politicians. Future generations would no doubt be pleased with a bigger economy and healthier budget position, but babies are, unfortunately, poor advocates for reform.

Heavily skewed and sometimes downright sensationalist traditional media coverage no doubt has some chilling effect on the willingness of our leaders to tackle these thorny issues.

And that’s before we have even got to the role of social media, where scare campaigns on tax policy can flourish even where those policies are entirely imaginary.

In the 2019 election, the so called ‘death tax scare campaign’ saw many widely shared Facebook posts – some shared by politicians – falsely claiming that Labor was planning to introduce an inheritance tax.[56]

The campaign was kicked off by the traditional media, with the Daily Telegraph and Channel Seven reporting that the ACTU supported an inheritance tax, and conflating this view with the ALP’s official policy agenda.[57] Minor parties, including One Nation and Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party, picked up the story on social media, where it was spread widely.

There may be some justifiable reciprocity here, given Labor’s own misleading scare campaign in 2016 on the Coalition’s alleged plans to ‘privatise Medicare’. But 2019 was evidence of the way that fear and falsehoods can be effectively weaponised via social media, a phenomenon that has only become all too clear in subsequent years.

In sum, social media and more shouty traditional media increase the costs for leaders thinking of dipping a toe into the water on tax reform. Public opposition gets louder much faster today, and reaches a higher vitriol point, than it did in the past.[58]

Tax reform is not for the faint of heart.

Almost too easy: the politics of the scare campaign

While the external environment undoubtedly creates its challenges, none of this is to let politicians themselves off the hook.

If sensationalism about tax is irresistible for the media, for the political class it appears an almost Pavlovian reflex.

The scare campaign rumblings begin at even the faintest suggestion of a tax change.

When Scott Morrison publicly flirted with a GST rise as Turnbull’s Treasurer, senior Labor and union figures were talking up the prospects of a major campaign within days.[59]

Tony Abbott’s campaign against the carbon tax is perhaps the ‘textbook’ modern scare campaign. With threats of $100 lamb roasts[60] and the alarming prospect of the South Australian city of Whyalla being ‘wiped off the map’,[61] it was certainly both scary and headline grabbing.

In a way, oppositions to tax changes are nothing new, tax reform has rarely been a bipartisan endeavour. Most major tax changes over the past 50 years – from capital gains tax to the GST – were contested by oppositions. In some cases, this opposition was egregiously opportunistic – like Keating’s attacks on John Hewson’s GST proposal in 1993, despite it being very similar to the policy Keating himself had fought for just a few years earlier.[62]

But what has changed is the way the politics is played. In the post-truth era the willingness of at least some politicians to embrace flagrant falsehoods, and to use modern media to distribute them far and wide, has most likely increased the potency of scare campaign tactics, and therefore the cost to the would-be tax reformer.

What about me? The psychology of tax reform

Of course, it’s easy to blame the vested interests, the experts, the media, or our venal politicians for the difficulty in achieving change.

But we ignore human psychology in crafting and selling reform at our peril.

Louis XIV’S finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, had this right more than 350 years ago when he declared ‘the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest possible amount of feathers with the smallest amount of hissing’.[63]

The hard fact is, some taxes are just more salient than others and therefore are always going to generate more hissing.

Indeed, this is the fundamental difficulty of the land tax/stamp duty reform. While it would improve efficiency and make many people better off, particularly those who move home more than average, it is a very hard sell.

The reasons are intuitive to any psychologist. Paying even a big whack of stamp duty (say $50,000) doesn’t seem that bad when you are purchasing something worth $1 million: it just makes an already really huge mortgage that little big huger.

On the other hand, an annual bill of $5,000 is unavoidably salient. We are conscious of every dollar as we make the payment.

The ACT Government was acutely aware of this challenge when it designed the transition path of its stamp duty/land tax reform.[64] It landed on a gradual 20-year transition path to keep the geese a little calmer, which we’re now halfway through. Tax reform is not for the impatient!

Anyone who is trying to advance some of the less popular tax changes needs to grapple with these types of design choices. We can’t simply pretend that unpopularity is irrelevant. In many cases, this will necessarily mean some down‑payment to smooth the transition.

Other human instincts can also prove challenging.

Another common barrier is reliance on the ‘easy outs’.

People will deflect from debates around specific tax changes with the argument we can’t do anything until governments have ‘Fixed multinational tax avoidance/cracked down on public service numbers and welfare cheats/insert easy solution to government’s budget woes here…’

The easy outs can prove an impossible barrier to sensible discussion since most of the things on the standard wish list are going to do little to shift the dial on the budget or the economy.

As then Treasurer Scott Morrison explained in 2016:[65]

There are a lot of fairytales out there at the moment. It is a fantasy to say all we need to do is something on multinational tax and somehow you can cut personal income tax rates.

Indeed, most of the ‘easy outs’ have already been extensively mined by governments, given their relative popularity.

Almost every budget of the past decade has contained at least some measures related to multinational tax avoidance, public sector budget cuts, reductions in foreign aid, increases to the tobacco excise, and/or new welfare integrity measures. These are not where the big future dividends are going to lie.

The only solution I see here is being very explicit in any tax discussion about what’s ‘big’ and what’s ‘small’. Tools like the Parliamentary Budget Office’s ‘Build your own budget’ tool[66] are powerful because they help people get a sense of the magnitude of particular changes and grapple directly with trade-offs.

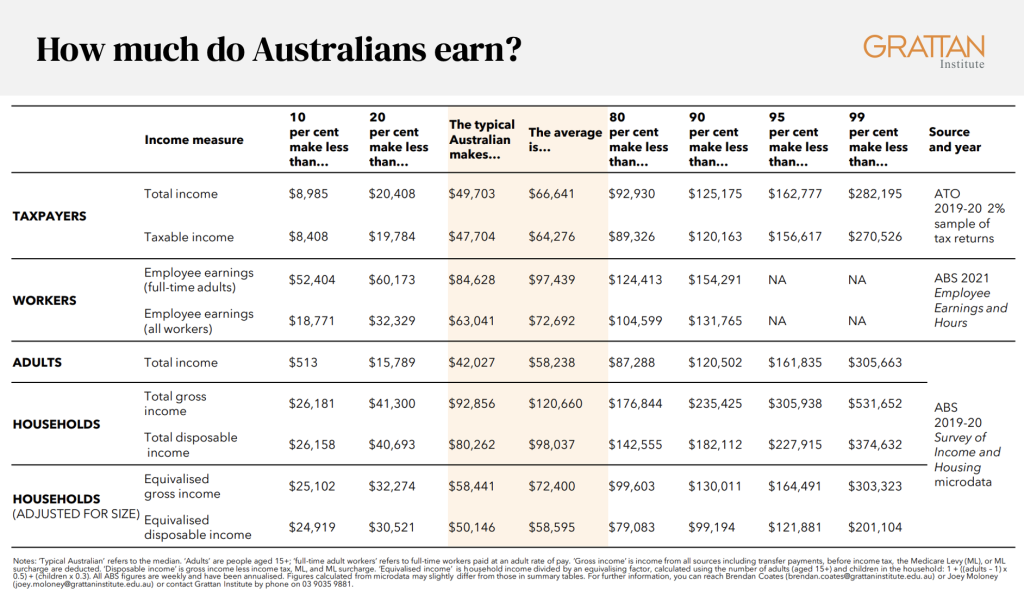

A related challenge is helping people understand the income and wealth distributions. Again, some high‑level understanding of what most Australians earn is important for understanding how significant particular tax proposals might be as well as the equity consequences.

Indeed, preferences for different policy interventions change when people have a better understanding of the actual distribution of income and wealth.[67]

But the vast majority of us consider ourselves to be ‘middle income earners’,[68] probably because the people we tend to live near and associate with are more likely to be in a similar tax bracket to us.

This is presumably why every year or so high earners from the media and political class kick off passionate debates about whether $200,000 is really a high income[69] – while, I suspect, the 97 per cent of Australians earning less than that amount just roll their eyes.[70]

Grounding debates in the facts matters. This is why Grattan puts out annual cheat sheets – ‘How much do Australians earn?’ and ‘How much do Australians own?’[71] – to coincide with the budget.

So, the upshot of everything I have just said is: tax reform is hard.

Does this mean we should just throw in the towel? Is it time for John to accept that his long career pushing for a better tax system has been simply tilting at windmills?

The answer is clearly no. It must be no. Tax reform is simply too big an economic prize to be left on the shelf.

So how can we chart a way forward through these challenging waters?

Part 3: What can history teach us?

It can be easy to reflect on recent tax reform atrophy and pine for some long-ago ‘golden era’ of reform. But the truth is, tax reform has never been easy.

So I want to round out this discussion with a short history lesson – five decades of tax reform in five minutes and what we can learn from it.

Let’s start in 1975. Many elements of our tax system today can be traced back to the 1975 Asprey tax review.[72] This was a comprehensive, independent review, commissioned by the McMahon Government to address concerns about bracket creep and tax evasion (sounds familiar!).

The review outlined the basic principles of efficiency, fairness and simplicity that remain our reform lodestars, and it made the case for many aspects of the system we have today, including fringe benefits tax, capital gains tax, and a broad-based consumption tax.

But the report initially had little impact. Landing in the final, tumultuous year of the Whitlam government, it was written off in the media as a ‘tax flop’,[73] and its main recommendations were not actioned.

It took another decade for momentum to build. In 1985, fresh off the Prices and Incomes Accord and the floating of the dollar, Hawke and Keating turned their attention to tax reform. They released a Draft White Paper on reform options and hosted a National Tax Summit with unions, business and community groups.[74]

These processes resulted in the implementation of some of the major Asprey recommendations, including a capital gains tax, negative gearing reform, fringe benefits tax, dividend imputation, and taxation of foreign source income.

But it was a case of ‘two steps forward, one step back’. A broad-based consumption tax was central to Keating’s original vision, but failed to win support and was dropped. And the pioneering negative gearing reforms were repealed two years later.

So the Asprey blueprint was partly implemented. Another long reform slumber followed. The next big push was John Hewson’s Fightback! platform for the 1993 election, which proposed, among other things, a broad-based consumption tax.[75] Fightback! proved to be a false start – Hewson lost the ‘unlosable’ election – but consumption taxes were back on the agenda.

It took another six years for the reform dream to become reality. Howard took a proposal for A New Tax System, which included the introduction of the GST, income tax cuts and the abolition of a host of inefficient state taxes,to the 1998 election. He narrowly won and the legislation ultimately passed in 1999, 24 years after the release of the Asprey report.

We’ve seen precious little in the way of significant, lasting tax reform since.

The landmark Henry review is close to celebrating its 14th birthday.[76] Most of its meaty recommendations remain untouched.

State and territory tax reform has also, mostly, been a non-starter, despite a succession of reviews converging on similar recommendations.[77]

So what should we take from this potted reform history? What can we learn from those rare moments when we managed to overcome the many barriers I outlined before?

I see four key steps for would-be reformers.

Step 1: Putting reform on the agenda

Our history shows that an external push is often needed to put tax reform on the agenda.

This can take the form of a crisis.[78] In 1985, fears about Australia’s economic decline and resentment about tax avoidance pushed the discussion forward.

In 1997, the High Court’s decision to strike down a key state tax left a significant hole in the states’ budgets and opened the reform window for the GST.[79]

The optimist in me can’t help but draw parallels with the High Court’s decision earlier this month to strike down Victoria’s electric vehicle levy. Perhaps we might have another golden opportunity for a grand intergovernmental tax reform bargain on our hands?

We’ve also learnt that consistent advocacy from outside politics can put tax reform on the agenda. Tax reform was hardly on the radar for the Howard Government until civil society groups – representing both social services and business – started championing the cause. ACOSS and ACCI, in particular, pushed in a coordinated way, culminating in a National Tax Reform Summit in 1996.[80]

The strong and united messaging put the GST, and tax reform, firmly back on the political agenda.

Today there are many groups that feel similarly. Federal independent Allegra Spender has been spearheading a push to unite academic, business and civil society leaders to build some consensus on the need for tax reform and the way forward.[81]

Step 2: Build a coherent package

Step two is putting together a reform package. While rewriting thousands of pages of the tax code at once would be a recipe for chaos, relying on incremental changes is probably not going to get the job done.

History shows that reform packages can work well.

In 1985, reforms that broadened the income tax base were bundled with income tax rate cuts and tax avoidance measures – a coherent story to sell to the public.[82]

And in 1999, the removal of narrow and inefficient – but lucrative – state taxes, and widely variable wholesale sales taxes, made sense in the context of the broader GST deal shoring up state budgets.[83]

Packages provide the opportunity to dull the sting of reform by sharing the costs more broadly and perhaps offering some compensation to the losers.

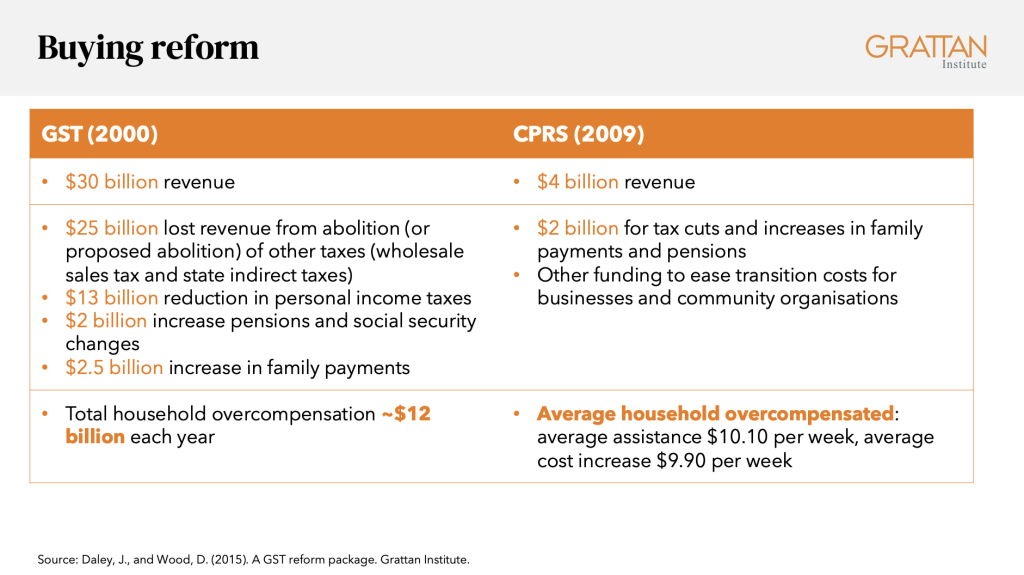

The major tax reforms of the past two decades have come at an upfront cost.

The GST package overcompensated households by about $12 billion a year, through personal income tax changes and increases to pensions and family payments.[84] This was a key part of its sales pitch. Former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry recalled that:

the distributional tables outlining the impact of the GST were the most ‘thumbed’ part of the documentation, certainly by those Treasury officers answering phone queries. Of course, it helped that every individual and family represented across all income levels appeared better off.[85]

Compensation packages are particularly important where there are equity implications for lower-income households. Australians tend to reject reforms that seem unfair.[86] But, crucially, potentially regressive reforms, such as broadening the base of the GST, can form part of larger, fairer reform packages. For example, the carbon tax package involved substantial assistance for households, particularly lower-income households, to address concerns that poorer households would be particularly affected by higher energy and food prices.[87]

Given the long‑term budget challenges, high‑cost packages of the type needed to ensure there are ‘no losers’ from tax changes are difficult to justify. But it is certainly possible to design packages with much lower upfront costs that still compensate vulnerable households. For example, Grattan’s previous work on the GST proposed a revenue positive package, with a 15 per cent GST, cuts to income taxes, and an increase in welfare payments, that would leave the lowest 40 per cent of income earners better off on average.[88]

Packages might also help address some of the other political economy challenges of reform. Ironically, opening up more fronts in the tax debate may quiet some of the more over the top reactions.

As Ken Henry has argued:

…if you give a lot of well-armed people only one target to shoot, it will take a pounding. Incrementalism sets up a single target on a battlefield occupied by well-resourced attack forces.[89]

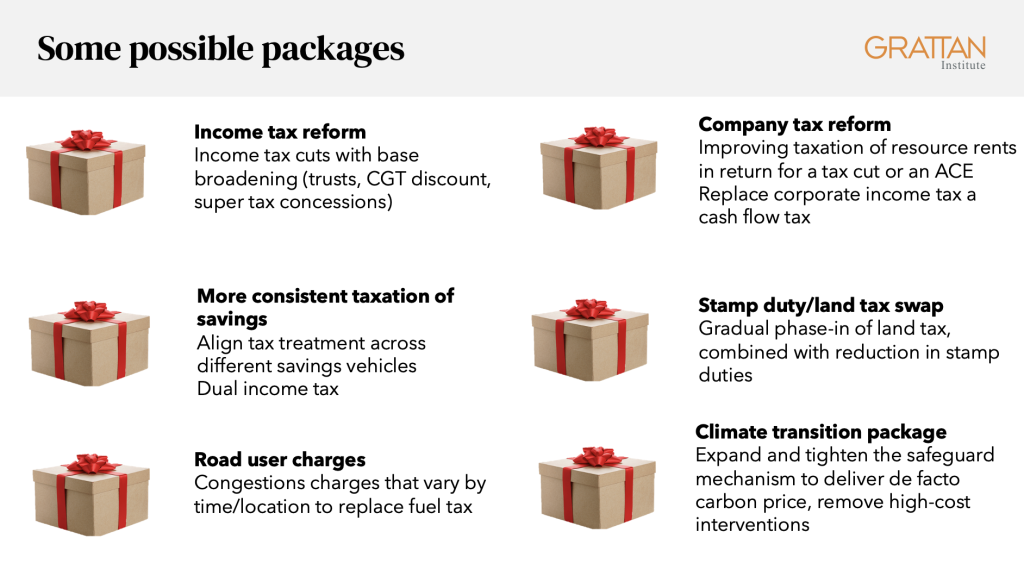

And while my goal tonight is not to opine on the ‘what’ of tax reform let me give a sense of some of the types of packages that a government could put forward.

- On income tax reform, we could return to the logic of 1985: broadening the income tax base by winding back loopholes and overly generous concessions, to support a cut in rates. This could include targeting discretionary trusts, super tax concessions; or reforming capital gains tax – either by reducing the CGT discount or returning to the indexation of gains. [90]

- Another package could tackle the inconsistent tax treatment of different savings vehicles, to reduce the distortion in savers’ choices and simplify the system.[91] This would mean lower taxes on interest from bank accounts and bonds, and somewhat higher taxes on other savings vehicles such as superannuation (which is very lightly taxed even after accounting for the long holding periods). An even ‘bigger bang’ version of the package would be a dual income tax where income from savings is taxed at a consistent low rate, regardless of source.

- On the corporate tax front, we could better tax resource rents to fund a company tax cut. We could also consider more wholesale reforms such as an allowance for corporate equity[92] or a cash flow tax.[93]

- For states, inefficient stamp duties could be swapped for land taxes over time, along the lines of the ACT Government’s gradual phase-in or Victoria’s switch for commercial and industrial property.[94]

- In the transport space, distance-based congestion charges that vary by location and time of day would be a more efficient replacement for the declining fuel tax base.[95]

- Finally, to aid the climate transition, the government could substantially expand and strengthen the Safeguard mechanism, while eliminating much higher cost interventions to reduce emissions such as the fringe benefits tax exemption for electric vehicles. The package would deliver both faster and lower cost emissions reduction.[96]

But while packages make a lot of sense, would‑be tax reformers cannot be too purist. Incremental changes in the right direction are still an improvement on the status quo, and in some cases these more incremental steps can ultimately take us towards more comprehensive packages.

Step 3: Embrace the vomit principle

The next step is making a compelling case for change. Complicated reforms that can’t be explained are unlikely to win support, and are more vulnerable to a scare campaign. We saw this in 2019 with the confusion about franking credits – irredeemably branded a ‘retirement tax’[97] – and in 1993, when John Hewson’s tortured explanation of the effect of a GST on the price of a birthday cake helped turn the tide of popular opinion against the new tax.[98]

Convincing the public of both the necessity of change, and the proposed solution, takes time and political capital. Howard and Costello spent two years and a lot of political energy highlighting the structural problems with Australia’s tax base prior to releasing their reform package in 1998.[99]

And despite some of the challenges I outlined earlier, there is nothing to say the same is not possible today.

It is a very long held view that the public will not tolerate more taxation. In the 18th century Edmund Burke remarked: ‘to tax and to please, no more than to love and to be wise, is not given to men’.[100]

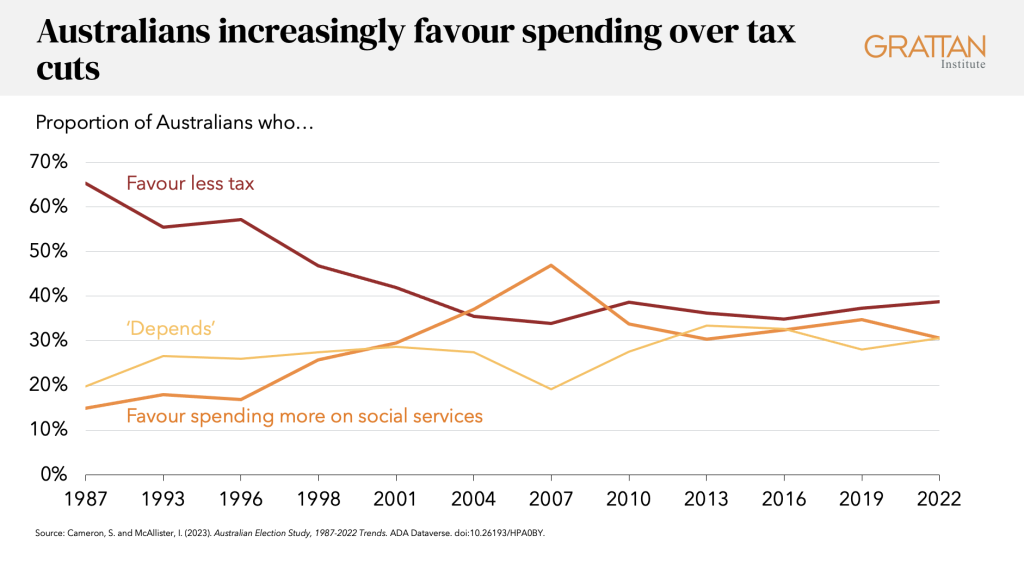

Australian attitudes are complicated. While no one likes to pay extra tax for the ‘fun of it’ many are more inclined when given a more concrete choice between better services and more tax.

The proportion of Australians favouring ‘less tax’ has declined since the late 1980s according to the Australian Election Study, and the proportion preferring ‘more spending on social services’ has risen. At the time of the 2022 election, 39 per cent indicated they would prefer less tax, 31 per cent more social spending and the remainder said ‘it depends’ – presumably on the nature of both the tax and spending increases.

My reading is that when our political leaders do the work of tilling the ground and explaining changes and why they are needed – hearts and minds can shift.

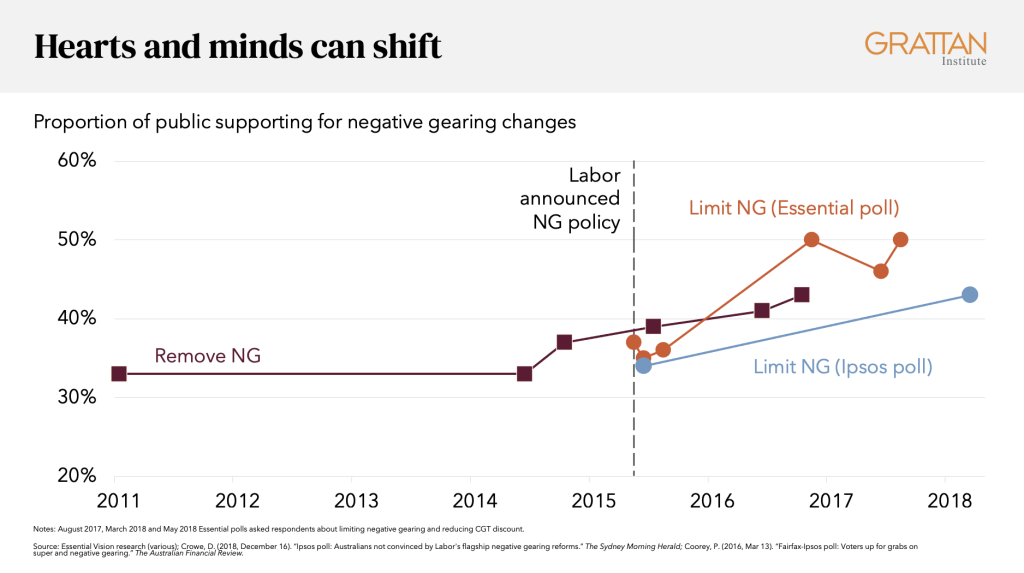

A more recent example, albeit one contrary to received wisdom, was the then‑Labor opposition’s 2016 policy to wind back negative gearing and reduce the capital gains tax discount.[101]

We have already discussed some of the public challenges that reform faced, but what is also worth remembering was that negative gearing had formerly been viewed as a ‘political untouchable’.

Indeed, since the Hawke government lost its nerve and reversed its decision to wind back negative gearing in 1987, it has been considered the ‘sacred cow’ of Australian politics.

When Labor announced it would introduce these changes to improve housing affordability and contribute to the budget bottom line in 2016,[102] just over a third of Australians supported removing or limiting negative gearing.

But, over time, as the then Opposition Treasury spokesperson, Chris Bowen, and others made the case, support gradually increased. Support for limits on negative gearing climbed almost 10 percentage points, from 34 per cent in March 2016 to 43 per cent in December 2018.[103] By the time of the 2019 election, the Australian Election Study estimated that 57 per cent of Australians supported limiting negative gearing.[104]

To me this is a textbook example of what some political strategists call the ‘vomit principle’ – repeat something until you feel like you are going to vomit. Only then are you cutting through.

Labor has of course since dropped the policy, and many reading the media commentary would have gained the impression that the tax reform agenda was deeply unpopular and to ‘blame’ for Labor’s surprise election loss in 2019. The reality was far more complex.[105]

In any case, it’s not just down to politicians to argue for reform. Successful tax reforms need a diverse cheer squad. Historically, academics, premiers, public policy institutions, and community groups have all been important advocates for tax reform.[106] Providing incentives for academics and non-profit organisations to participate in public debate would be a useful step to building these coalitions today.[107]

Step 4: Make it stick

Somewhat dispiritingly, even after these hurdles have been overcome and tax reform has been passed, the job isn’t done. Tax issues tend to linger on the agenda, often for entire parliamentary terms, and reforms sometimes don’t stick.[108] As we’ve just seen, negative gearing reforms were undone after just two years in 1987. The carbon tax and mining tax were repealed. The Perrottet Government’s hesitant steps towards stamp duty reform were wound back by the new NSW Labor Government.[109]

But in other cases the controversy does die down after reform is enacted. Sometimes social norms change quickly – for example, in Stockholm, congestion charging was much more popular after it had been implemented than before, and many people did not even remember that they once opposed the idea.[110]

In Australia, plenty of tax changes that were controversial at the time – the GST, fringe benefits tax, capital gains tax – are now so entrenched that there is no constituency or any visible public appetite for their removal.111]

Reforms are more likely to stick if they create positive feedback loops – for example, if they result in institutional shifts, make advocates of reform winners, or if businesses make big investments under the new regime.[112]

Taking the GST as an example, the ATO and businesses made significant investments in the infrastructure for administering the new scheme; and the changes to federal financial relations created a key constituency – state governments – who had a strong interest in its continuation.

Conclusion: tax reform, down but not out

This evening we are not only celebrating Professor Freebairn’s body of work, but also his move to the role of Emeritus Professor, and hopefully a little more relaxed pace.

So as John moves to this next phase, what is the hope for tax reform?

I for one remain optimistic.

First and foremost I don’t think we have much choice. A slow‑burning platform is still on fire, and over the coming decade, the gap between our spending needs and our tax system’s capacity to meet them without ever higher taxes on employment income will be stretched to breaking point.

More and more, questions of sustainability and intergenerational fairness are raised about our current tax mix. Expect them to get louder and louder over the coming decade without action.

Similarly, tax must come into the conversation if we are going to deliver our policy objectives in other areas, including the green transition.

Second, I am confident that our leaders can make a positive case. While I have focused on the challenges tonight, I am also heartened by the leadership we are seeing on difficult reforms in other areas.

Over the past three months both the Commonwealth and state governments have made strong commitments to boost the supply of housing through politically challenging reforms to planning laws. If they can pull it off, this would be a huge economic and social reform, and one that has been in the ‘too hard basket’ for many decades.

As a reform proposition, making the case for greater housing density is probably of the same order of difficulty as making the case for major tax changes, and yet we are seeing both levels of government go after it in a big way.

Third, I think there is appetite across a broad swathe of interested parties to shift the dial. Allegra’s Spender’s tax reform roundtables suggest at least a consensus amongst business, academia, and civil society that something needs to change, even if there is not yet broad agreement on the reform priorities.

A process to harness this agreement, ideally led and shaped by government, could help move the conversation forward.

Finally, I have confidence in the Australian people to see through the noise. Scare campaigns and a shouty media are one thing, but if state and federal government can hold their nerve in the ‘rule in/rule out game’ long enough to make a positive case for change, and keep making it, history shows that people can be brought along.

Tax reform is hard but it’s not impossible. It’s time we woke up from our slumber and became a little less afraid and a little more Freebairn.

Footnotes

- I would like to thank Elizabeth Baldwin for her help preparing this speech and to other Grattan staff members who have provided intellectual inspiration for much of the material.

- Freebairn, J. (2002). “Opportunities to Reform State Taxes.” Australian Economic Review 35.4, pp. 405–422.

- Freebairn, J. (2005). Income Tax Reform: Base Broadening to Fund Lower Rate. Melbourne Institute.

- Freebairn, J. (2012). “Personal Income Taxation.” Economic Papers: A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy 31.1, pp. 18–23.

- Freebairn, J. (2015). “Reconsidering royalty and resource rent taxes for Australian mining.” Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 59.4, pp. 586–601.

- Freebairn, J. (2011). “A Better and Larger GST?” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 22.3, pp. 85–100.

- Cao, L. et al. (2015). Understanding the economy-wide efficiency and incidence of major Australian taxes. Treasury Working Paper 2015-01.

- Coates, B., and Moloney, J. (2023). Victoria should swap stamp duties for a broad-based property tax: Submission to Victorian Legislative Council inquiry into land transfer duty fees. Grattan Institute.

- Chalmers, J. (2023, September 22). Final Budget Outcome shows first surplus in 15 years. Treasury. https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/jim-chalmers-2022/media-releases/final-budget-outcome-shows-first-surplus-15-years

- As the strong labour market continues to surprise on the upside and commodity prices outstrip forecasts.

- For example, the projected average annual growth in NDIS spending over the decade was cut from 13.8 per cent in the October 2022 Budget to 10.4 per cent in the May 2023 budget without any explanation or policy change to justify the more conservative growth figure.

- Productivity Commission (2023). “A competitive, dynamic and sustainable future.” Advancing Prosperity: 5-year Productivity Inquiry report (volume 3, p. 49).

- Hewson, J. (2014). “The Politics of Tax Reform in Australia.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 1.3, pp. 590–599.

- Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth), Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth), Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986 (Cth)

- Australian Taxation Office (2023). Taxation statistics 2020-21, Individuals statistics, chart 7.

- Beal, E., D’Hotman, D., Hamilton, S., Heeney, L., and Lamont, K. (2021). Bye-bye tax returns: A standard deduction for lower, simpler, and fairer taxes. Blueprint Institute.

- For example, Blueprint Institute estimated that a standard deduction of $3000 could eliminate 7–9 million tax returns per year, saving around $750 million a year in accounting and legal fees: ibid.

- Carter, A., and Breunig, R. V. (2023). Tax Bunching of Very High Earners. Evidence from Australia’s Division 293 Tax. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 04/2023; Hamilton, S. (2018). Optimal deductibility: Theory, and evidence from a bunching decomposition. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 14/2018; Johnson, S., Breunig, R., Olivo-Villabrille, M., and Zaresani, A. (2023). Individuals’ responsiveness to marginal tax rates: Evidence from bunching in the Australian personal income tax. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 11/2023.

- Breunig, R. V., Deutscher, N., and Hamilton, S. (2022). Hundreds and thousands: bunching at positive, salient tax balances and the cost of reducing tax liabilities. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 12/2022.

- Wood, D. (2021). John Button Oration: The Next Generation’s Australia. Grattan Institute; Wood, D., and Griffiths, K. (2019). Generation gap: Ensuring a fair go for younger Australians. Grattan Institute.

- Bensusan-Butt, D. (1979, p. 176). “The target for tax reform.” British Tax Review 3, p. 168-177.

- Machiavelli, N. (1532). The Prince (W. Marriott, Trans.). Project Gutenberg.

- Davis, M. (2011, February 1). “Mining industry dug deep to shaft Rudd over tax.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/mining-industry-dug-deep-to-shaft-rudd-over-tax-20110201-1acfi.html ; Saulwick, J. (2010, July 1). “Gillard cuts mining tax deal.” The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Zappone, C. (2010, June 24). “Ceasefire between miners and government.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/business/ceasefire-between-miners-and-government-20100624-z14a.html

- Wood, D. (2019, May 16). “The lowest blow of this election campaign may have come from a firm of real estate agents.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/may/16/the-lowest-blow-of-this-election-campaign-may-have-come-from-a-firm-of-real-estate-agents

- Maiden, S. (2019, May 13). “Welfare groups slam negative gearing ‘scare campaign’.” The New Daily. https://www.thenewdaily.com.au/news/election-2019/2019/05/13/negative-gearing-scare

- Daley, J., and Wood, D. (2016, March 3). “A low-cost way to derail the housing debate.” Inside Story. https://insidestory.org.au/a-low-cost-way-to-derail-the-housing-debate/

- Hansard. (2016). House of Representatives: Questions Without Notice: 3 March 2016, p. 3008.

- After a number of days of media questioning, the report commissioner was revealed to be financial services firm Bongiorno and Partners: Medhora, S. (2016, April 12). “Negative gearing report: financial services firm had vested interest, says Labor.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/apr/12/negative-gearing-report-financial-services-firm-had-vested-interest-says-labor

- Wood, D., and Griffiths, K. (2018). Who’s in the room? Access and influence in Australian politics. Grattan Institute.

- Ibid.

- Heffernan, M. (2013, October 22). “McMillan sees brighter tax days ahead.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/business/mcmillan-sees-brighter-tax-days-ahead-20131022-2vz83.html

- Pascoe, M. (2016, September 20). “Labor and coalition agree to keep tax lurk.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/labor-and-coalition-agree-to-keep-tax-lurk-20160920-grjzsp.html

- The donation was made on 22 August 2013: Australian Electoral Commission (2014). Australian Salary Packaging Industry Association – 2013-14 Donor Return. https://transparency.aec.gov.au/AnnualDonor/ReturnDetail?returnId=28803

- Includes donations from Australian Salary Packaging Industry Association Limited and National Automotive Leasing & Salary Packaging Association; to Australian Labor Party, Australian Labor Party (State of Queensland), and Liberal Party of Australia: Australian Electoral Commission (2023). AnnualDetailed Receipts – 2015-16. https://transparency.aec.gov.au/AnnualDetailedReceipts

- Shorten’s letter was dated 4 May 2016: Shorten, B. (2016). An Open Letter to all NALSPA Members. https://announcements.asx.com.au/asxpdf/20160505/pdf/4371b3mt95zbck.pdf . The donation was made on 12 May 2016: Australian Electoral Commission (2016). National Automotive Leasing and Salary Packaging Association – 2015-16 Donor Return. https://transparency.aec.gov.au/AnnualDonor/ReturnDetail?returnId=40096

- Productivity Commission (2023). “Managing the climate transition.” Advancing Prosperity: 5-year Productivity Inquiry report (volume 6).

- Daley, J. (2021). Gridlock: Removing barriers to policy reform. Grattan Institute.

- The proposal was for a staged reduction in tax rates, starting with small businesses, with all businesses paying 25 per cent by 2026-27: Morrison, S. (2016). Budget Speech 2016-17. https://archive.budget.gov.au/2016-17/speech/Budget-Speech.pdf

- Treasury’s internal and commissioned modelling found that the company tax cut would increase long-term gross national income (GNI) by about 0.6 per cent compared to the baseline scenario (assuming the lost tax revenue was made up through increases in personal income tax), whereas independent modelling of a cut in the company tax rate to 22 per cent found that GNI would be 0.2 per cent lower in the long run, compared to the baseline scenario: Dixon, J., and Nassios, J. (2016). Modelling the Impacts of a Cut to Company Tax in Australia. Centre of Policy Studies; The Treasury (2016). Economy-wide modelling for the 2016-17 Budget. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/160503_Economy-wide-modelling.pdf . See also: Daley, J., Coates, B., and Young, W. (2016). Submission to Senate Inquiry into the Treasury Laws Amendment (Enterprise Tax Plan) Bill 2016. Grattan Institute.

- Feld, L., and Heckemeyer, J. (2011). “FDI and taxation: A meta‐study.” Journal of Economic Surveys 25.2, pp. 233–272.

- Lewis, R. (2023, February 28, p. 1). “Super switch to class war.” The Australian.

- Credlin, P. (2023, February 23, p. 11). “Labor tries for a socialist super grab by stealth.” The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/labor-tries-for-a-socialist-super-grab-bystealth/news-story/4b854d1955b0fdefc36b3a21c1a833f0

- Chambers, G. and Commins, P. (2023, March 1, p. 1). “Super-sized broken promise.” The Australian, 1 March, p. 1. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/super-tax-discounts-worth-50bn-jim-chalmers/news-story/c2b9737432eef7826b37f4036cf8fe6b

- There were 1,246 unique articles in the Australian media related to Labor’s super tax changes in the four weeks from 22 February 2023, when the Treasurer first publicly discussed the $3 million cap on superannuation balances in the media: Grattan analysis of Factiva database.

- Treasury (2022), Budget October 2022-23 Factsheet: expanding Paid Parental Leave. https://archive.budget.gov.au/2022-23-october/factsheets/download/factsheet_parental_leave.pdf

- There were 282 unique articles in the Australian media related to paid parental leave in the four weeks from 14 October 2022: Grattan analysis of Factiva database.

- There were 689 unique articles in the Australian media on superannuation tax concessions in the month after the 2016-17 budget: Grattan analysis of Factiva database.

- Korporaal, G. (2016, May 31). “Coalition blind to superannuation debacle.” The Australian. https://theaustralian.com.au/business/opinion/coalition-blind-to-superannuation-debacle/news-story/4dd804aac95cb066f52e6de41a9a0f47

- Gallagher, D. R. (2016, May 13). “Superannuation tax debate infested with the politics of envy”. The Australian Financial Review.

- Karp, P. (2016, May 23). “Ray Hadley tells Scott Morrison the Coalition may ‘perish’ over superannuation changes.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/may/23/ray-hadley-tells-scott-morrison-the-coalition-may-perish-over-superannuation-changes

- Murphy, K. (2017, April 24). “Liberal boss declines to warn off challengers to Kelly O’Dwyer.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/apr/24/liberal-boss-declines-to-warn-off-challengers-to-kelly-odwyer

- There were 184 unique articles in the Australian media on the PaTH (Prepare, Trial, Hire) program in the month after the 2016-17 budget: Grattan analysis of Factiva database.

- Durkin, P. and Bleby, M. (2016, February 15). “Investors may lose $1000 a year under Labor’s negative gearing plan.” Australian Financial Review. http://www.afr.com/news/politics/investors-may-lose-1000-a-year-under-labors-negative-gearing-plan-20160214-gmtnvk

- Daley, J., and Wood, D. (2016). Hot property: negative gearing and capital gains tax. Grattan Institute.

- Warren, M. (2020). “Fake News Case Study during the Australian 2019 General Election.” Australasian Journal of Information Systems 24.

- Carson, A., Gibbons, A., and Phillips, J. B. (2021). “Recursion theory and the ‘death tax’: Investigating a fake news discourse in the 2019 Australian election.” Journal of Language and Politics 20.5, pp. 696–718.

- Daley, J. (2021). Gridlock: Removing barriers to policy reform. Grattan Institute.

- Medhora, S. (2016, February 7). “Malcolm Turnbull: I’m not convinced GST increase to 15% will boost economy.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/feb/07/malcolm-turnbull-im-not-convinced-gst-increase-to-15-will-boost-economy

- Taylor, L. (2014, July 14). “Carbon tax savings: Labor has a bone to pick with Coalition.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jul/14/carbon-tax-savings-labor-bone-pick

- Pedler, E. (2011, April). “Tony Abbott visits Whyalla, speaks against proposed mining and carbon taxes.” ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2011/04/27/3201383.htm

- Tilley, P. (2021). 2000: A new tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 14/2021.

- Cited in Keen, M. and Slemrod, J. (2021). Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom through the Ages. Princeton University Press.

- ACT Government. (2020). Tax Reform. https://www.treasury.act.gov.au/taxreform

- Murphy, K. (2016, January 24). “GST debate: Scott Morrison backs need for option to raise tax as part of reforms.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/jan/24/gst-debate-scott-morrison-backs-need-for-option-to-raise-tax-as-part-of-reforms

- Parliamentary Budget Office (2023). Build your own budget. https://www.pbo.gov.au/publications-and-data/data-and-tools/build-your-own-budget

- Hoy, C., and Toth, R. (2019). Aligning preferences for redistribution of right and left wing voters by correcting their beliefs about inequality: Evidence from a randomized survey experiment in Australia. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 04/2019.

- Ibid; Hoy, C., and Mager, F. (2021). “Why Are Relatively Poor People Not More Supportive of Redistribution? Evidence from a Randomized Survey Experiment across Ten Countries.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13.4, pp. 299–328.

- Hobman, J. (2022, July 14). Aussie bloke exposes why $200k isn’t a big salary: “Barely cuts it.” Daily Mail Australia. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11011735/Aussie-businessman-exposes-200k-year-NOT-big-salary-anymore.html ; Martin, P. (2021, June 8). “Other Australians don’t earn what you think. $59,538, is typical.” The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/other-australians-dont-earn-what-you-think-59-538-is-typical-162251

- Grattan analysis of Australian Taxation Office 2019-20 2% sample file.

- Coates, B., and Moloney, J. (2023). Grattan Institute’s 2023 Budget cheat sheet on what Australians actually earn and own. Grattan Institute.

- Tilley, P. (2020). Post-War Tax Reviews and the Asprey Blueprint. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 15/2020.

- James, K. (2007). “We of the “never ever”: The History of the Introduction of a Goods and Services Tax in Australia.” British Tax Review 3, pp. 320-248

- Tilley, P. (2021). 1985 reform of the Australian tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 07/2021.

- Tilley, P. (2021). 2000: A new tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 14/2021.

- Tilley, P. (2021). Australia’s future tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 17/2021.

- Freebairn, J., Stewart, M., and Liu, P. X. (2015). Reform of State Taxes in Australia: Rationale and Options. Melbourne School of Government; Tilley, P. (2022). State and Territory tax reform. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 02/2022. There are some notable exceptions, like the ACT Government’s commitment to replace stamp duties with land tax over 20 years.

- Henry, K. (2020, June 29). “History lesson teaches how to do tax reform again.” Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/policy/tax-and-super/history-lesson-teaches-how-to-do-tax-reform-again-20200628-p556wu ; Kelly, P. (2011). “How to design and deliver reform that makes a real difference: what recent history has taught us as a nation.” In S. Vincent, E. A. Lindquist, & J. Wanna (Eds.), Delivering Policy Reform (pp. 43–51). ANU Press; Perram, N. (2013). Tax reform political parties and the prisoners’ dilemma: address to the Treasury. https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-perram/perram-j-20130829

- Perram, N. (2013). Tax reform political parties and the prisoners’ dilemma: address to the Treasury. https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-perram/perram-j-20130829

- Brown, J. (1999). “The Tax Debate, Pressure Groups and the 1998 Federal Election.” Policy and Society 18.1, pp. 75–101; Tilley, P. (2021). 2000: A new tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 14/2021.

- Quail, J. (2023, September 8). “‘Too important to ignore’: Independent MP Allegra Spender steps up tax reform push.” news.com.au. https://www.news.com.au/finance/money/tax/too-important-to-ignore-independent-mp-allegra-spender-steps-up-tax-reform-push/news-story/34444e138fdd185f3269301f7463f650

- Smith, J. (2004). Taxing Popularity: The Story of Taxation in Australia. Australian Tax Research Foundation; Tilley, P. (2021). 1985 reform of the Australian tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 07/2021.

- Tilley, P. (2021). 2000: A new tax system. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 14/2021.

- Daley, J., and Wood, D. (2015). A GST reform package. Grattan Institute.

- Henry, K. (2009). Lessons from Tax Reform Past. Treasury. https://treasury.gov.au/speech/lessons-from-tax-reform-past

- Henry, K. (2023). The need for ambitious tax reform. https://nofibs.com.au/speech-ken-henry-on-the-need-for-ambitious-tax-reform ; Kelly, P. (2016). Economic reform: A lost cause or merely in eclipse?. Australia and New Zealand School of Government. https://anzsog.edu.au/app/uploads/2022/06/Alf-Rattigan-2016-Paul-Kelly-lecture.pdf

- Australian Council of Social Service. (2011). The Clean Energy Future package, households on low incomes and the community services sector. ACOSS Paper 177; Daley, J., and Wood, D. (2015). A GST reform package. Grattan Institute.

- Daley, J., and Wood, D. (2015). A GST reform package. Grattan Institute.

- Henry, K. (2023). The need for ambitious tax reform. https://nofibs.com.au/speech-ken-henry-on-the-need-for-ambitious-tax-reform

- Rationales for winding back some of these concessions are explored in: Wood, D., Coates, B., Duckett, S., Hunter, J., Terrill, M., Wood, T., and Emslie, O. (2022). Orange Book 2022: Policy priorities for the federal government. Grattan Institute; Wood, D., Griffiths, K., and Chan, I. (2023). Back in black? A menu of measures to repair the budget. Grattan Institute.

- Varela, P., Breunig, R., and Sobeck, K. (2020). The taxation of savings in Australia: Theory, current practice and future policy directions. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Policy Report 01/2020.

- Sobeck, K., Breunig, R., and Evans, A. (2022). Corporate Income Taxation in Australia. Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Policy Report 01/2022.

- Garnaut, R., Emerson, C., Finighan, R., and Anthony, S. (2020). “Replacing Corporate Income Tax with a Cash Flow Tax.” Australian Economic Review 53.4, pp. 463–481.

- Coates, B. (2023, May 24). “Victoria shows how to abolish stamp duty.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/victoria-shows-australia-how-to-finally-abolish-stamp-duty-once-and-for-all-205646

- Terrill, M. (2023, October 18). “No matter who collects EV revenue, we have to charge smartly.” Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/policy/energy-and-climate/no-matter-who-collects-ev-revenue-we-have-to-charge-smartly-20231015-p5ecbv

- For a discussion see Productivity Commission (2023). “Managing the climate transition.” Advancing Prosperity: 5-year Productivity Inquiry report (volume 6).

- Bongiorno, F. (2019, May 19). “Clearing the scrub.” Inside Story. https://insidestory.org.au/clearing-the-scrub/

- Sakzewski, E. (2019, March 1). “John Hewson was favourite to become PM when Mike Willesee asked this question about a cake.” ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-03-01/mike-willesee-interview-current-affair-john-hewson-career/10862440

- Eccleston, R., and Marsh, I. (2011). “The Henry Tax Review, Cartel Parties and the Reform Capacity of the Australian State.” Australian Journal of Political Science 46.3, pp. 437–451.

- Burke, E. (1774), cited in Keen, M. and Slemrod, J. (2021). Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom through the Ages. Princeton University Press.

- Labor proposed to remove negative gearing for non‑business investment assets, but still allow taxpayers to negatively gear investments in new properties. Investment losses could still be used to offset any investment gains in the same financial year, or future capital gain made on the assets. Labor also proposed to halve the capital gains tax discount from 50 per cent to 25 per cent. See: Parliamentary Budget Office (2019). Negative gearing and capital gains tax (CGT) reform: Policy costing. https://www.pbo.gov.au/elections/2019-general-election/2019-election-commitment-costings/2019-election-commitment-costings/negative-gearing-and-capital-gains-tax-cgt-reform-per414

- “Shorten unveils negative gearing changes to ‘level housing playing field.’” (2016, February 13). ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-13/bill-shorten-pledges-negative-gearing-changes/7165854

- Coorey, P. (2016, Mar 13). “Fairfax-Ipsos poll: Voters up for grabs on super and negative gearing.” The Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/politics/fairfaxipsos-poll-voters-up-for-grabs-on-super-and-negative-gearing-20160313-gnhlho ; Crowe, D. (2018, December 16). “Ipsos poll: Australians not convinced by Labor’s flagship negative gearing reforms.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/ipsos-poll-australians-not-convinced-by-labor-s-flagship-negative-gearing-reforms-20181216-p50mjn.html

- Cameron, S. and McAllister, I. (2019, p. 8). The 2019 Australian Federal Election: Results from the Australian Election Study. https://australianelectionstudy.org/wp-content/uploads/The-2019-Australian-Federal-Election-Results-from-the-Australian-Election-Study.pdf

- Wood, D. (2019, May 23). “Self-interest didn’t swing the election results, but the scare campaign did.” The Guardian. https://grattan.edu.au/news/self-interest-didnt-swing-the-election-results-but-the-scare-campaign-did/

- Eccleston, R. (2013). “The Tax Reform Agenda in Australia.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 72.2, pp. 103–113; Hewson, J. (2014). “The Politics of Tax Reform in Australia.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 1.3, pp. 590–599; Tilley, P. (2020). Post-War Tax Reviews and the Asprey Blueprint. ANU Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper 15/2020; Tran-Nam, B. (2019). “The Goods and Services Tax (GST): The public value of a contested reform.” In J. Luetjens, M. Mintrom, & P. `T Hart (Eds.), Successful Public Policy: Lessons from Australia and New Zealand (1st ed., pp. 235–255). ANU Press.

- Daley, J. (2021). Gridlock: Removing barriers to policy reform. Grattan Institute.

- Eccleston, R. (2013). “The Tax Reform Agenda in Australia.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 72.2, pp. 103–113; Kelly, P. (2016). Economic reform: A lost cause or merely in eclipse?. Australia and New Zealand School of Government. https://anzsog.edu.au/app/uploads/2022/06/Alf-Rattigan-2016-Paul-Kelly-lecture.pdf

- Coates, B. (2022, June 22). “Perrottet’s grand stamp duty plan ends with a whimper.” The Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/policy/tax-and-super/perrottet-s-grand-stamp-duty-plan-ends-with-a-whimper-20220621-p5avag

- Terrill, M. (2019). Why it’s time for congestion charging: Better ways to manage busy urban roads. Grattan Institute.

- Henry, K. (2010). “Changing taxes for changing times.” Economic Roundup 1. Treasury.

- Mettler, S., and Soss, J. (2004). “The Consequences of Public Policy for Democratic Citizenship: Bridging Policy Studies and Mass Politics.” Perspectives on Politics 2.1, pp. 55–73; Patashnik, E. (2008). Reforms at Risk. Princeton University Press.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.