Published by Inside Story, Tuesday 20 March

Labor’s plan to abolish refunds of unused imputation credits has ignited a political firestorm. But the claims and counter-claims about who will be affected by the policy have obscured, rather than illuminated, the real story.

Labor claims most of those hit by the change are wealthy retirees who are not paying their fair of tax. Scott Morrison counters that abolishing refunds of unused imputation credits will mainly hurt low-income earners. So, who’s right?

Part of the confusion stems that the fact that data on what retirees earn, what they own and what tax they pay is highly fragmented. Personal income tax returns provide only a patchy picture of the earnings and wealth of retirees. Superannuation payouts have been tax-free since 2006: they don’t even have to be declared on personal income tax returns. And drawdowns of savings other than superannuation to fund retirement — whether shares, bank deposits or investment property — are not declared as income.

ABS surveys tell us which retirees own shares and what other assets they own, but not whether they receive imputation credits or claim other deductions, or precisely how much income tax they pay. Meanwhile data on self-managed super funds — which will pay most of the extra tax — is not connected to members’ personal income tax returns or retirees’ other assets.

Picking up these various threads and weaving them into a coherent story about who would pay more tax under Labor’s reforms is no easy task. But here goes.

Australia’s dividend imputation system ensures that shareholders are not taxed twice on corporate profits. “Franking credits” are attached to dividends paid to shareholders, reflecting any company tax already paid, and can be used to offset any personal income tax the shareholder owes to the Tax Office.

Refunds for unused franking credits were introduced in 2001. The logic was simple: people with no or low income should receive equivalent tax treatment as others. Any unused or “excess” franking credits left after someone had reduced their taxable income to zero were returned via a cheque from the government.

Labor’s plan would restore the pre-2001 system: most taxpayers could still use imputation credits to offset other tax owing to the ATO, but those with no income tax liability — mainly retirees and their self-managed super funds — would no longer be able to claim cash refunds.

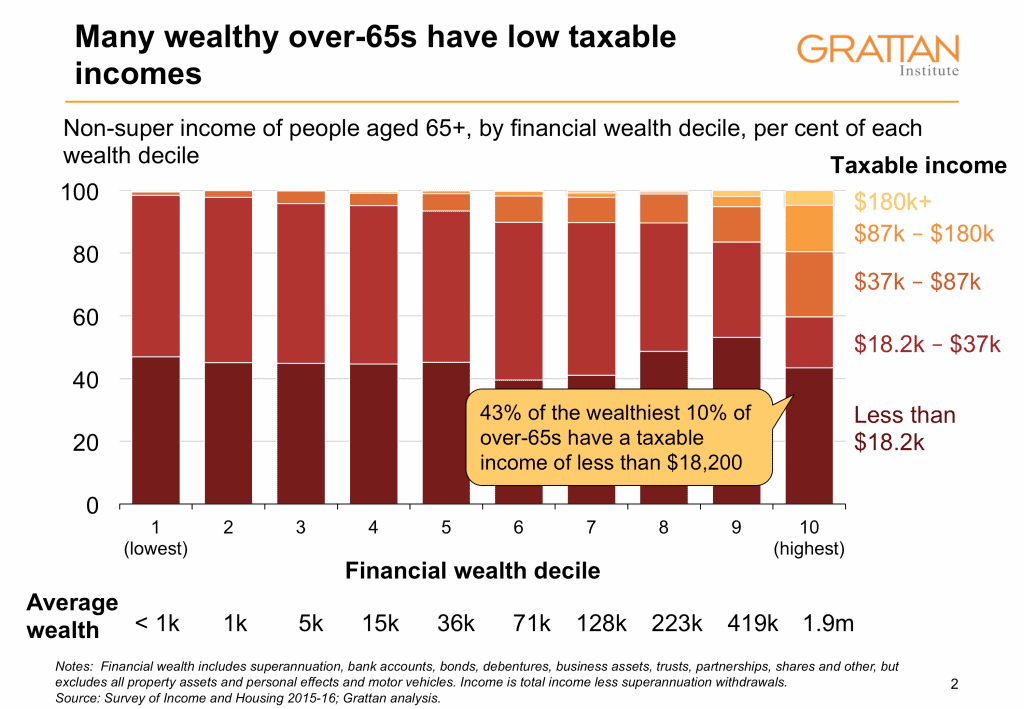

The government claims that 54 per cent of people affected by Labor’s policy — some 610,000 individuals — have taxable incomes of less than $18,200. And it says that 86 per cent of the value of all franking credits refunded are received by those with taxable incomes of less than $87,000 a year.

These claims are deeply misleading. Taxable income ignores the largest source of income for many wealthier retirees: tax-free superannuation.

Take the example of a self-funded retiree couple with a $3.2 million super balance, plus their own home, and $200,000 in Australian shares held outside super. Even drawing $130,000 a year in superannuation income, and $15,000 a year in dividend income, they would report a combined taxable income of just $15,000, and pay no income tax whatsoever.

And is the treasurer seriously suggesting that 610,000 retirees actually get by on less than $18,200 a year, or nearly 20 per cent below the poverty line? If that were anywhere close to the real story, it would signal a full-blown retirement-incomes crisis.

Whoever they are, Scott Morrison’s 610,000 “low-income earners” are clearly not the poorest retirees. Few, if any, are maximum-rate pensioners.

A single retiree receiving the full age pension has an income of $23,318 a year, and more if they earn extra income in dividends from shares. All this income would show up as taxable income if they submitted a personal income tax return — as required to claim refundable imputation credits.

Some maximum-rate couple pensioners could have a taxable income below $18,200. The maximum-rate pension for a couple is $32,000 a year, or $16,000 each. So one half of such a couple could receive dividends of up to $2200 a year and still receive a full pension. The maximum hit for them from Labor’s policy would be $660 a year.

But most of those affected by Labor’s policy who declare taxable incomes of less than $18,200 a year are far from being low-income earners. They are either part-pensioners, or not receiving any pension at all. And they’re drawing much of their income from tax-free superannuation.

When superannuation withdrawals are stripped out from income in ABS survey data, as is done to calculate taxable income, almost half of the wealthiest 10 per cent of over-sixty-fives report incomes of less than $18,200. On average, though, they have wealth of nearly $2 million — and that’s even before considering the value of their home or any other property assets they might own.

Of course, there will be examples of seniors with low incomes being hit hard by the change. But media reports highlighting their plight rarely tell the full story.

When we hear of a part-pensioner with a taxable income of less than $18,200 a year being hit by Labor’s plan, it is worth asking why they’re only receiving a part-pension in the first place. As a single retiree, they must have either an assessable income of more than $27,700 a year or assets exceeding $253,750 (excluding the family home if they’re a homeowner) or $456,750 (if they rent). To be on a part-pension, a retired couple will have an income of between $40,000 and $78,000 a year, and assets of between $380,500 and $1 million.

The full story is that many part-pensioners are relatively wealthy, especially because the home is excluded from the pension assets test. Half of all pension payments go to those with assets of more than $500,000. Almost 20 per cent of payments go to those with assets of more than $1 million. They’re clearly much better off than the bottom 40 per cent of retirees, who draw a full age pension.

Nor is it clear that incomes are the best way to judge just how well-off retirees are. People build up retirement savings during their working lives, which they then draw down to fund their retirement. Or at least that’s the idea.

One reason so many retirees report such low incomes is because they only draw down very slowly on their retirement savings, or not at all. One recent study found that at death the median pensioner still had 90 per cent of their wealth as first observed.

Many retirees who report having very low incomes in retirement have substantial retirement nest eggs. A retiree homeowner with $1 million in super, enough to make them ineligible for a full pension, but drawing down at the minimum required rate of 4 per cent, would declare an annual income of just $40,000 a year. And although $40,000 a year, even tax-free, may sound low relative to average full-time pre-tax earnings, retirees tend to have lower expenditure because they are no longer saving and typically are no longer paying off a mortgage. This is a well-off group; few working-age Australians have the chance to accumulate $1 million in superannuation, and pay off their own home, before they retire.

It’s also worth remembering who will pay most of the extra tax under the Labor policy. About 33 per cent will be paid by (mainly wealthy) individuals who own shares directly, 60 per cent will be paid by self-managed superannuation funds (typically held by wealthier retirees), and the remaining 7 per cent will be paid by super funds regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority.

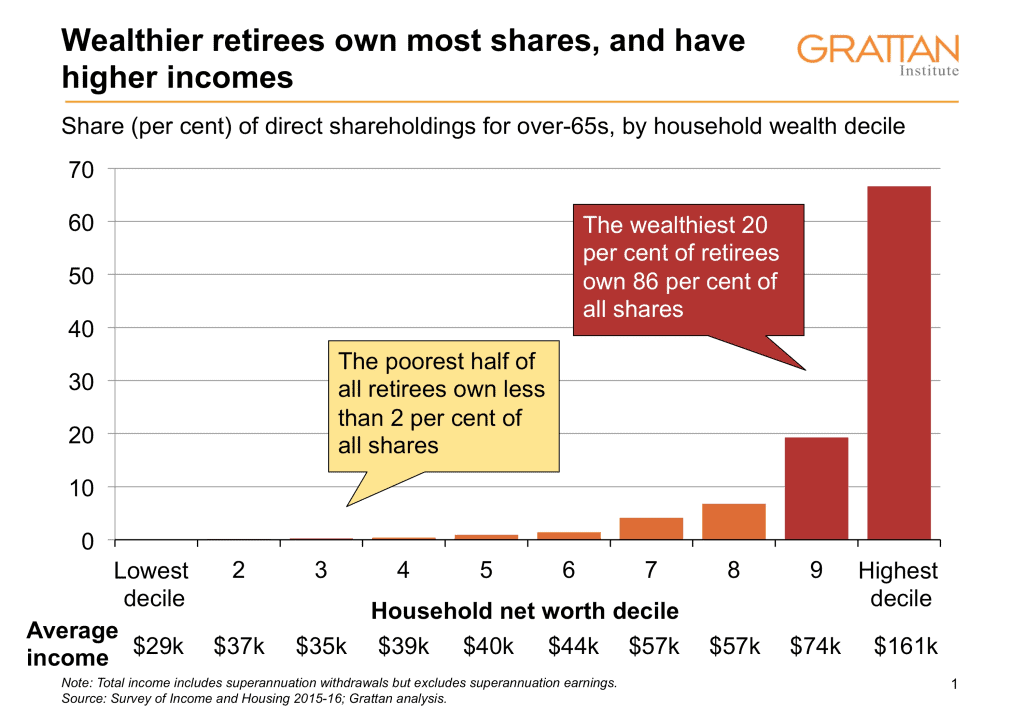

The poorest half of all retirees own less than 2 per cent of all shares held directly. By contrast, the wealthiest 40 per cent of retirees own 97 per cent of all shares held directly, and the wealthiest 20 per cent alone own 86 per cent of all shares held directly.

Among self-managed superannuation funds (primarily held by wealthier retirees), half of the refunds are currently going to people with balances over $2.4 million.

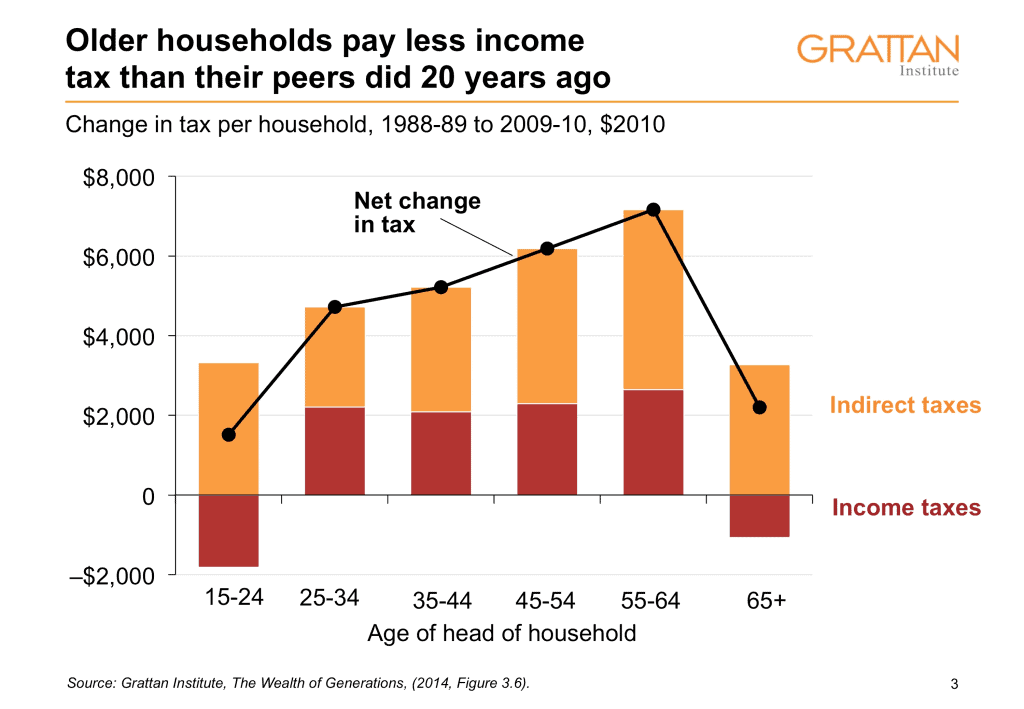

For more than a decade, superannuation tax concessions have been absurdly generous to older people on high incomes. They are one of the major reasons older households pay less income tax in real terms today than they did twenty years ago, even though their workforce participation rates and real wages have jumped.

These age-based tax breaks help to explain why the proportion of seniors paying tax almost halved in twenty years, from 27 per cent in 1995 to 16 per cent in 2014. The rise of these “taxed-nots” coincides with the introduction of the Senior Australian Tax Offset in 2000, and tax-free super withdrawals in 2007.

Generous super and other age-based tax breaks have been funded by deficits. The accumulating debt burden will disproportionately fall on younger households.

The government’s claim that abolishing refundable imputation credits will mainly hit low-income earners is deeply misleading. Taxable income ignores the largest source of income for many wealthier retirees: tax-free superannuation.

Retirees with the lowest taxable incomes are likely to be wealthier self-funded retirees — precisely the group Bill Shorten wants to target. About 14,000 maximum-rate pensioners and 200,000 part-pensioners will be hit, but the vast bulk of the revenue coming from wealthier retirees. That’s the real story.